Photo by Corbis Historical/Getty Images

As of 2024, the organization Legacy CCC has erected statues in 42 states honoring the young men of the Civilian Conservation Corps. All of them portray a White CCC worker, despite the roughly 300,000 African Americans—from unemployed cooks to college-educated administrators—who worked in the CCC.

The CCC was one of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s most popular New Deal programs. It offered steady work to young men between the ages of 18 and 25. Roughly 3 million men signed up between 1933 and 1942.

Black enrollees generally worked in segregated camps and performed tasks dependent on their locations. These duties included damming and drainage work, recreational development, reforestation, malaria eradication, and wildlife conservation.

Company 526, one of Ohio’s Black CCC camps, took shape by 1934 at Camp Logan.

Camp Logan’s location in Ohio’s scenic Hocking Hills region was marvelous. A reporter for the local Lancaster Eagle-Gazette newspaper testified that “the view one gets from the officers’ mess hall down a beautiful valley of various streets, pine and rock formations, is surely the most wonderful sight that has struck the eyes of the writer for years.”

Before the camp’s closure in 1937, the young men at Camp Logan improved over 2,000 acres including the Cantwell Cliffs, Rock House, and Rockbridge areas.

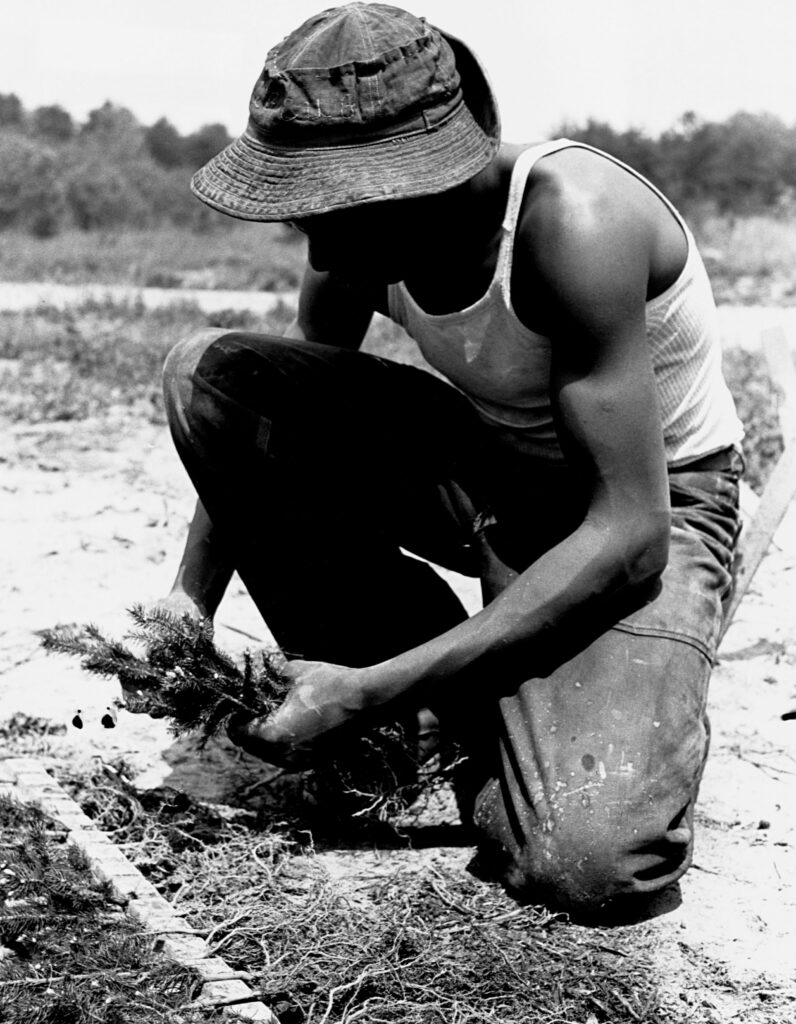

Photo By Corbis Historical/Getty Images

Company 526 restored a region damaged by decades of clearcutting to feed the coal and iron industries and from erosion caused by unsustainable farming. One of Co. 526’s priorities was reforesting Hocking State Forest and, all told, they planted 300,000 pines, hemlock, tulip popular, and black walnut trees.

Here, in a photograph from Beltsville, Maryland in 1940, the blazing sun bathes a CCC enrollee’s back as he holds a sapling in his left hand while pruning it with his right. The surrounding area is barren, and his work planting countless trees—one by one—will gradually transform this landscape into a dense forest. This is an arduous task, as the smudges and creases on his work denim reflect. He has discarded his standard issue denim shirt to mitigate the oppressive heat.

Reforestation took place alongside infrastructural improvement. At Rock House, Company 526 painstakingly cut steps from sandstone cliffs leading to the cave, blazed a looped trail, erected a stone bridge and safety walls, and constructed picnic shelters from blighted American chestnut all while reforesting this 750-acre site.

Photo by Getty Images/Bettmann Archive

Company 526 also built the infrastructure that opened the region for automobile tourism. Rural southeastern Ohio—including Hocking County, part of Ohio’s Appalachian region—generally lacked quality roads, and these road-building projects paid off immediately.

In this photograph, a CCC enrollee concentrates while operating a road surfacing roller. Behind him, a flattened dirt pathway stretches toward the horizon flanked by scattered pines. This young man’s careful work resulted in what was, perhaps, the first paved road in the region.

By 1935, tourists flocked to Cantwell Cliffs. A press release affirmed hundreds of visitors during the summer with vehicle license plates from neighboring Kentucky and West Virginia. Attesting to this work’s transformative nature, Black CCC chaplain G. Lake Imes remarked, “Boys who never had anything but a hoe in their hands have become experts in handling tractors, trucks and road machinery.”

Each day at a CCC camp began with reveille at 6 a.m. followed by a workday lasting from 8 a.m.-4 p.m. Three hearty meals daily helped the average worker gain 8-14 pounds and grow an inch in height. After a communal dinner, enrollees relaxed before lights-out at 10 p.m.

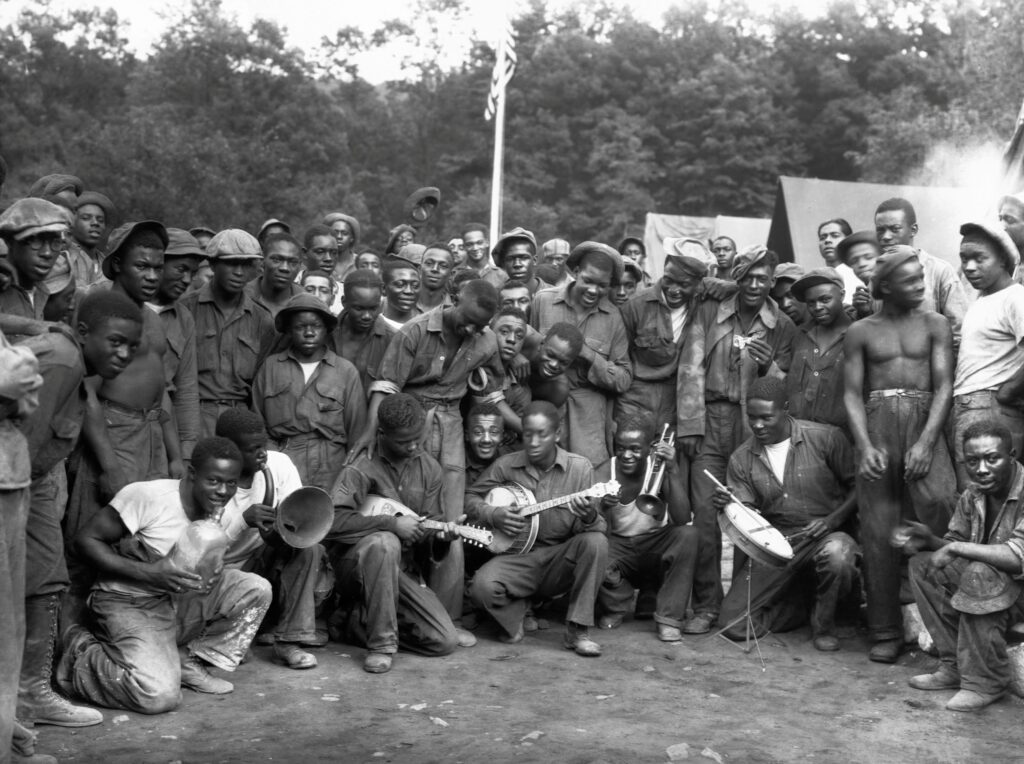

This 1933 photograph captures the vibrancy of camp life. Men along the bottom row play their instruments, from banjos to horns, laying a distinct soundtrack for the camp. One man pokes his head through the crowd and gleefully smiles in the photograph’s center, while others look on with expressions ranging from surprise to disinterest.

Others, still, laugh at goofy compatriots, yell to the photographer, and wave their hats. One enrollee’s shirtless muscles testify to the grueling work of rehabilitating the American landscape.

CCC staff offered academic classes in subjects from basic literacy to advanced science. Lectures in Black camps covered topics from spiritual life to Black history. All told, some 13,000 African American enrollees across the nation completed training in first aid and 15,000 attained literacy.

Company 526 formed baseball, softball and football teams. In 1935, the Camp Logan Bucketballers scored victories over Camps Athens, Hocking, and Stoney Creek. They even played local teams, like during a narrow 11-10 victory against the village of Laurelville. Contests against White camps and towns represented a moment when segregation momentarily fell away as these young men united over friendly competition.

Photo by Corbis Historical/Getty Images

Here, a quartet of enrollees in Yanceyville, North Carolina in 1940 pose in a collective embrace during a choral performance. They are caught up in the moment—exchanging sly grins and appearing caught off guard—as they perhaps sing a popular Depression-era tune or a traditional African American hymn. Note their pressed, spotless leisure khaki uniforms in comparison to the heavy and soiled denim workwear depicted in the previous photos.

Enrollees participated in events outside camp, too. Many communities reacted apprehensively to unfamiliar CCC workers in their midst. At times, Black CCC enrollees faced hostility and discrimination, and were even the victims of violence. Other locales, however, welcomed Black CCC members’ participation in civic life.

Hundreds of thousands of Black CCC workers shared in the struggles and triumphs that came with transforming the American landscape. Though many faced notable hardships and a general state of racial discrimination, many still found this transformative experience both valuable and gratifying. Frank “Tech” Wilson, who served in Company 517 in Harrison County, Indiana, believed that his time in the CCC was “the greatest part of my life.”

Today, roughly 5 million tourists annually visit Ohio’s Hocking Hills State Park. As visitors climb this region’s forested hills, they navigate trails and mount steps carved into the land by the CCC. Few likely pause and reflect on the fact that some of those young men—the African Americans who served in Co. 526—were climbing hills all their own as they navigated the potential benefits and discriminatory pitfalls afforded by their experience in the CCC.

Learn More:

Brian McCammack, Landscapes of Hope and the Great Migration in Chicago (Cambridge, MA.: Harvard University Press, 2017).

Neil Maher, Nature’s New Deal: The Civilian Conservation Corps and the Roots of the American Environmental Movement (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Olen Cole Jr., The African-American Experience in the Civilian Conservation Corps (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1999).