Photo by John van Hasselt – Corbis/Sygma/Getty Images

This photograph captures the SS Ancon, an American steamship, that brought 1500 Barbadian laborers to work on the Panama Canal project on September 2, 1909. Previous attempts at building a canal to unite the Pacific and Atlantic sailing routes had proven costly failures. This latest attempt by the United States followed closely on the heels of Panama’s declaration of independence from Colombia in 1903.

The canal proved an economic advantage to the United States. As owners of the canal from 1914-1999, the United States charged fees to all who crossed it, and many of the ships that passed through it docked in ports on the U.S. east and west coasts.

Before the Panama Canal was completed, ships either had to sail around South America or unload and transport cargo across land before reloading on the opposite coast. Opening a waterway between the Pacific Ocean and the Caribbean Sea saved actors in the world economy significant sums.

But none of these benefits would have been possible without the laborers who risked life and limb to complete the massive task.

The building of the Panama Canal began during a period of U.S. expansionism, and the canal’s construction continued a tradition wherein Black and Indigenous labor built the infrastructure for imperial flows of goods, wealth, and people.

While West Indians migrated to Panama to work on previous attempts to build a canal and for the Panama Railroad, the U.S.-backed Panama Canal project that began in 1904 attracted a much larger influx of migrant workers.

Laborers from Jamaica, Martinique, Guadeloupe, and Spain all arrived for work, but the bulk of migrant laborers came from the Caribbean island of Barbados.

Barbados was a British colony so heavily entrenched in the sugar plantation industry that the landscape (both physical and economic) was intrinsically tied to that one crop.

After Emancipation freed enslaved populations in the 1830s, agricultural laborers on the island were often locked into a “located labor” system. Their rent consisted of working on plantations for five days a week, which meant they had little time to earn real wages.

Because there was little land on the island that was not part of a plantation and thus nowhere else to live, a large portion of Barbados’s population was locked into unpaid labor. Moreover, outbreaks of cholera in 1854, typhoid in 1866, and smallpox in 1903, as well as hurricanes in 1893 and 1898, further eroded stability on the island. By the turn of the twentieth century, population density exacerbated the rising poverty levels. Emigration was very attractive.

The Isthmian Canal Commission in charge of construction knew this and eagerly recruited migrant workers from Barbados between 1904 and 1909.

Contracted workers were mainly men, but women also traveled unofficially, and as construction went on many workers sent for their families. Soon, so many people were migrating voluntarily that contracts became mostly unnecessary.

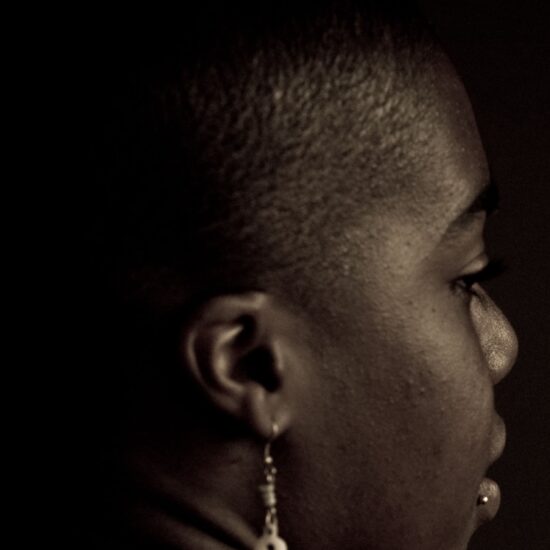

The migrants sailed from Barbados to Panama on steamships such as the SS Ancon. Because of the way migrant laborers traveled—on deck, exposed, crowded together, and without much comfort, as we see in this photograph—they became known as “deckers.”

Between 1904-1916, over 45,000 Barbadians migrated to Panama to work on the canal, roughly a quarter of the island’s population.

Upon arrival, migrants lived mostly in the Canal Zone, a semiautonomous region that was technically part of Panama but operated and governed by the United States.

The earliest generation of migrants did the hardest work, literally digging out the space for large boats to cross the fifty miles between the coasts. Deaths from industrial accidents, falls from scaffolding, and disease were common.

Throughout the building of the canal and for decades after its completion, these migrants and their descendants worked on an unequal pay scale, where mostly white U.S. citizens were paid on the “gold roll,” and the mostly Black, mostly West Indian migrants were paid on the “silver roll.” The distinctions began a form of segregation within the Canal Zone that permeated clubs, schools, and housing as well as pay.

The SS Ancon American steamship, pictured here, was the first to “officially” cross the Panama Canal when it opened in 1914.

Upon completion of the canal, some West Indian migrants returned to their island territories, some moved on to Cuban sugar plantations, and some went to the United States, but most stayed in Panama.

While pay was unequal, laborers worked and saved. The money they accrued and the money they sent as remittances allowed them to send children to schools abroad, to buy land in their home territories, and to begin to build wealth that funded migrations for generations to come.

Listen to the author:

Learn more:

Maurer, Noel and Carlos Yu. “What T.R. Took: The Economic Impact of the Panama Canal, 1903-1937.” The Journal of Economic History 68, no. 3 (September 2008): 686-721.

Newton, Velma, Kathleen Drayton, and Woodville Marshall editors. The Barbados-Panama Connection Revisited: 2004 Lectures Commemorating Migration from Barbados to Panama 1904-1914. Barbados Museum & Historical Society, National Cultural Foundation and the Department of History and Philosophy, University of the West Indies, Cave Hill Campus, 2014.