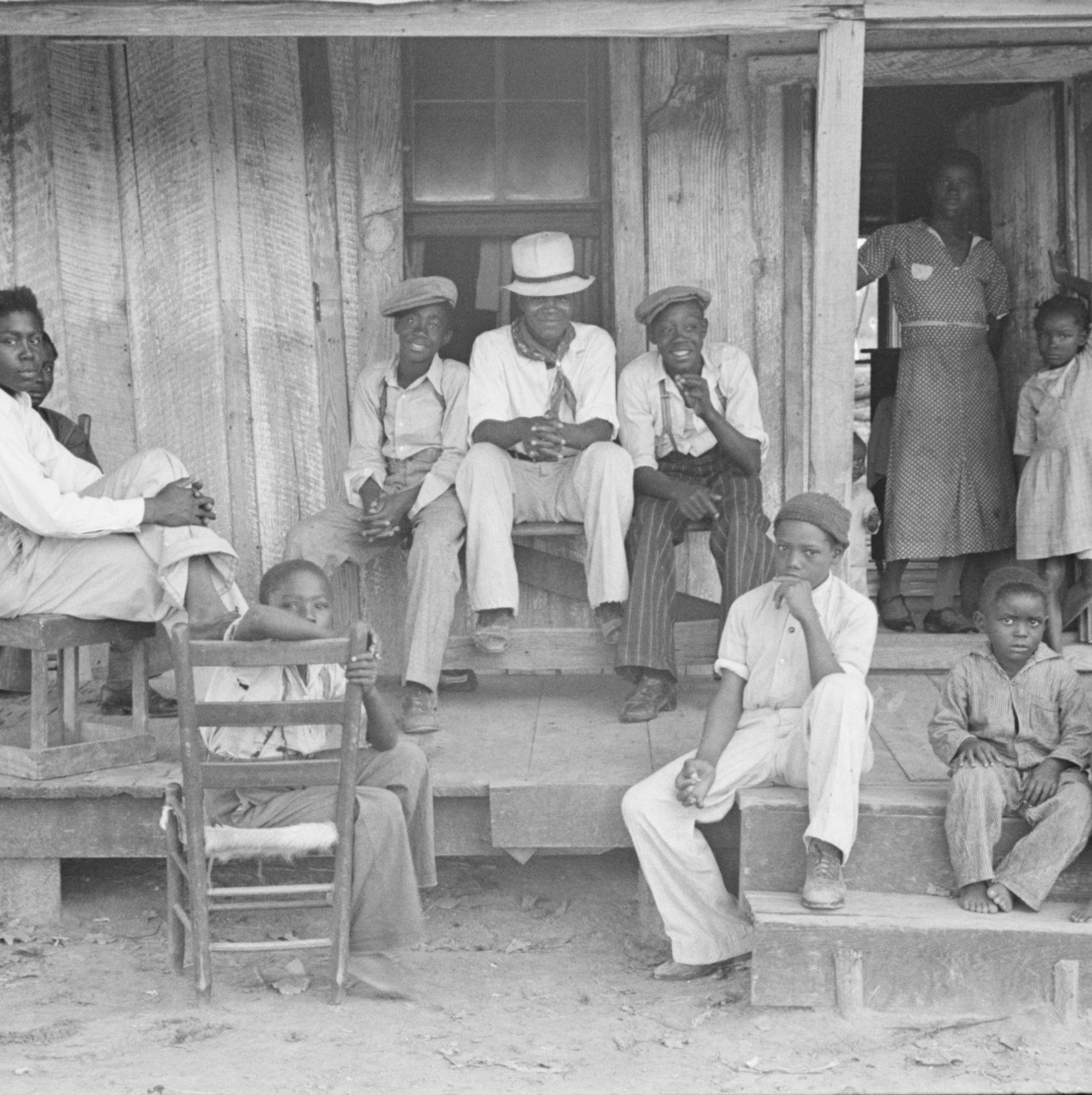

Photo by Ben Shahn/Library of Congress/Archive Photos/Getty Images

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, America “discovered” the southern sharecropper. As journalists, photographers, filmmakers, labor organizers, and government officials fanned out across the United States, many of them documented the lives and labors of the nation’s rural poor.

Although the sharecropping system had emerged from the wreckage of Reconstruction as a system designed to keep southern Black farmers poor, landless, indebted, and dependent on white landowners, it soon ensnared many poor whites as well. The deepening rural impoverishment remains familiar almost a century later in the indelible images captured by photographers working for the New Deal’s Farm Security Administration—Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Marion Post Wolcott, Arthur Rothstein, Ben Shahn, and others.

And yet, even sharecroppers didn’t work on Sunday—and that’s when Shahn caught up with this large African American family near Little Rock, Arkansas, in fall 1935.

The prototypical representation of Black and white sharecroppers found in most FSA photography emphasized poverty, loneliness, destitution, and grinding work. After all, these “sociologists with cameras” were tasked with demonstrating the necessity of government rural rehabilitation programs to alleviate poverty.

But Shahn saw something very different on this Sunday.

Sharecropping was, above all, a family business, and most sharecropping families were large, like the one shown in the second photograph below. The head of the household—usually, but not always, male—was not paid a wage for working in the fields. Instead, he contracted his entire family’s labor in return for a portion of the proceeds of the final crop.

The more labor that family could deliver, the better, which put a premium on getting as many children into the fields at as young an age as possible. A larger crop—at least until the bottom dropped out of cotton prices—might mean a better “settle” at the end of the year. Accumulation meant escaping from the vise of debt and maybe, just maybe, purchasing your own plot of land someday. But that aspiration, dating back to the broken Reconstruction promise of “forty acres and a mule” and requiring constant labor, would not interfere with a Sunday.

The first photograph shown above depicts a “sharecropper on Sunday,” sitting on the porch in front of his home. Simply yet well dressed, filling the frame, he appears both relaxed and alert, fully in command, if somewhat skeptical of his interlocutor. In a second, closely related photo (likely shot a few moments later), he gestures with his right hand while holding a cigarette, as if recounting a story to the viewer—in this case, Shahn.

But if the Black sharecropper brought his family’s labor to the bargaining table with the white landowner, another tool was required to assure a fair settle: a pencil. The school year was short for Black children needed in the fields, but the person—more often than not the sharecropper’s wife or eldest daughter—who could keep written track of loans, expenditures, and sales proved a valuable asset to the family. We cannot tell what the young woman just behind the sharecropper is writing or calculating, but her thoughtful expression and her grasp on her writing implement suggest its importance.

The older children in this picture taken the same day seem to be dressed in their Sunday best. Store-bought shoes certainly were a luxury for sharecroppers, yet only the three youngest in this photograph remain bare-footed. Jaunty hats, suspenders, and nice slacks also suggest that this particular Arkansas Black sharecropper’s family spent what little income there was at the end of the year on Sunday clothing (or the cloth to make it). The relaxed and open pose of this family stands in notable contrast to the display of rural hardship and desperation one finds in many portraits of southern Black life in the Depression era.

In a second group portrait of sharecropping children (probably more than one family in this case), we see a similar set of markers of dignity and Sunday pride: erect posture, faces up to the camera; hats, jewelry, shoes, eyeglasses, nice dresses, even a full suit worn by the eldest boy. Indeed, generational ranking stands out in this photograph: it seems clear that as children grew older, they acquired more trappings of respectability.

At least one child, however, seems willing to directly express her impatience with the photographer and his demands. We can also see here the family’s pencil holder and her older sister from the first photograph, second and fourth from the left.

Shahn’s Sunday images remain striking for another reason; in contrast, for example, to Dorothea Lange’s famous photograph of a Mississippi plantation owner dominating the frame in which he clearly wields power over his Black subjects, Shahn’s photographs here privilege Black experience without any visible white presence or interference.

To be sure, any Black sharecropper living in the Arkansas Delta in the 1930s remained beholden to powerful whites—his landlord, the local merchant, the sheriff, even his poor white neighbors and fellow sharecroppers. Yet the presence of those white authority figures does not intrude on this Sunday morning interlude.

It is a shame that Shahn failed to record the names of these children and their family, for it would be illuminating to learn what happened to them in the coming decades. Agricultural “reform” during the 1930s destroyed the last tenuous hold Black families like this held on the land; war jobs called the young men and women away from the fields to Little Rock and Memphis, or to tank factories in Detroit and shipyards in Mobile and Oakland. Tractors soon displaced family labor.

Those who stayed scrounged work as agricultural day laborers; many departed in the second Great Migration to Chicago, Los Angeles, or St. Louis. There were many good reasons for rural Blacks to leave the South behind, but these photographs remind us that something was lost as well.

Listen to the author:

Learn More:

Nicholas Natanson, The Black Image in the New Deal: The Politics of FSA Photography (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1992).

Howard Kester, Revolt Among the Sharecroppers (Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, 1997).

Michael K. Honey, Sharecropper’s Troubadour: John L. Handcox, the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union, and the African American Song Tradition (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013).

Sarah Meister, Dorothea Lange: Words and Pictures (New York: MOMA, 2019).

Ben Shahn, The Photographs of Ben Shahn (Washington, DC: Library of Congress, 2008).

Ben Shahn: Passion for Justice, New Jersey Public Broadcasting Authority, 2001.