Photo by Bettmann/Getty Images

In 1773, Phillis Wheatley Peters started a tradition of Black women’s portraiture in America. She published her portrait (above) deliberately to challenge white supremacists who did not believe an enslaved Black woman could write internationally celebrated poetry.

Wheatley Peters taught the public what a Black woman poet looked like. At that time, she probably was thinking more of her current critics, rather than laying the foundations for future generations to continue the practice of challenging racism through portraiture. Nevertheless, her picture demonstrated the importance of Black women leaders defining their own public image.

Wheatley Peters was the first American woman of any race to publish her portrait in her own book, which she titled Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral (1773). In the portrait, she sits at a writing table with a quill and considers her next lines. The poet wears cap over her hair with a modest dress and an apron, which subtly references her domestic labors.

The text circling the portrait refers to her as a “servant,” but the Wheatley family had enslaved her since she had arrived in Boston at age seven or eight. The education she earned eventually helped her attract supporters on both sides of the Atlantic and secure her freedom.

Adding a portrait to a book was not an easy task in 1773, but Wheatley Peters and her patrons needed this portrait to prove that she wrote her poems. They paid an artist to engrave the picture, and it cost extra for the publisher to print the portrait in the book too.

Her work won recognition from many leading Americans. Thomas Jefferson believed she wrote the lines but deemed them unoriginal, while George Washington admired her “great poetical Talents,” especially when she celebrated him with them (see His Excellency General Washington).

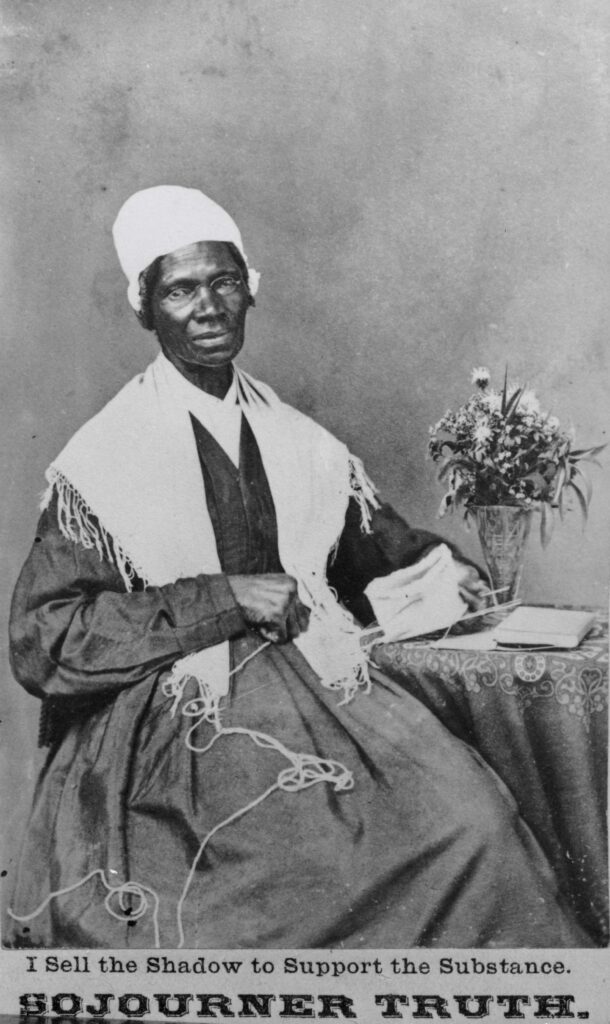

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Sojourner Truth had surely seen Phillis Wheatley Peters’ portrait. Antislavery activists distributed the picture through the antebellum period as an argument against racism and slavery. Born around 1797 in New York state, Truth remained enslaved until 1826 when she escaped and became a leading antislavery and women’s rights reformer.

Like Frederick Douglass, also a formerly enslaved person, Truth defined her public image through her photographs.

Douglass portrayed himself in the familiar fashion of male leaders, often seated in a powerful pose wearing a professional suit and a determined look. In contrast, Truth—like Wheatley Peters before her—depicted herself as a modest woman in a domestic space.

By the 1860s, when Truth’s photograph was taken, she spoke on public stages throughout the United States. However, in her portrait (above) she sits knitting next to a vase of flowers to convince viewers of her domesticity and feminine respectability.

Truth regularly posed for photographs in this manner. Unlike most public figures of the era, she copyrighted her portraits and sold them herself instead of allowing a professional photographer to do it. She wanted full control over them and used the money to support herself and her causes.

The women’s rights newspaper The Revolution, run by women’s rights leaders Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, reported in 1869 that “as the substance [Truth] had often been sold, it was quite a pleasure for her to sell the shadow [photograph] herself.”

Photo by Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Truth and Wheatley Peters inspired later activists like Mary Church Terrell (above) and Ida B. Wells-Barnett (below) to embody modern ideals of Black feminine respectability in their portraits.

After the Civil War, the two women led movements to advance civil rights, abolish lynching, and win voting rights for Black women. Mary Church Terrell became among the first Black women to earn undergraduate and master’s degrees. In 1896, the National Association of Colored Women elected her as its first president.

Similarly, journalist Ida B. Wells-Barnett penned numerous articles to support her causes and founded the Alpha Suffrage Club. The leaders weren’t just known to Americans, they gave public lectures all over the world.

Photo by Fotosearch/Getty Images

In their portraits, Wells-Barnett and Terrell offer a feminine version of the early twentieth-century refined and successful “New Negro” model of Black leadership. The two women represent themselves as respectable and far more elegant than Wheatley or Truth. Terrell and Wells-Barnett had more freedoms, money, and education. As a result, their portraits depict them wearing finer clothes, jewelry, and fashionable hairstyles.

Terrell wrote in her autobiography that she didn’t like the stereotypes of educated Black women wearing “bad-looking, unbecoming hats, long dresses with the hem ripped half out, and shoes run down at the heel.” She wanted to use her portraits to change stereotypes and encouraged members of her organization to do the same. Feminine fashions were part of her political strategy.

Wheatley Peters, Truth, Wells-Barnett, and Terrell created a tradition of using portraiture to define public images of Black women’s leadership. Their portraits won them recognition and visibility that continues today. The pictures appear in museums, documentaries, and textbooks. Through their portraits, these women gave representation to their ideal, their power, and Black womanhood.

Learn more:

Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw. “‘On Deathless Glories Fix Thine Ardent View’: Scipio Moorhead, Phillis Wheatley, and the Mythic Origins of Anglo-African Portraiture in New England.” In Portraits of a People: Picturing African Americans in the Nineteenth Century. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006.

Michelle Duster. Ida B. the Queen. New York: Atria/One Signal Publishers, 2021.

Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby. Enduring Truths: Sojourner’s Shadows and Substance. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2015.

Allison K. Lange Picturing Political Power: Images in the Women’s Suffrage Movement. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2020.

Alison M. Parker. Unceasing Militant: The Life of Mary Church Terrell. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2020.

“Phillis Wheatley Redrawn,” Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery’s Portraits podcast, https://npg.si.edu/podcasts/phillis-wheatley