Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

The American Civil War generated one of the largest migrations of Black Americans in the nation’s history. During the war, enslaved people believed that if they could reach the Union Army, they could secure their freedom. As the Union Army campaigned southward, thousands of enslaved people fled to its camps. Union officers and soldiers were quickly overwhelmed because caring for the enslaved was not their priority.

However, the growing presence of enslaved refugees in Union camps forced the Union to address enslaved people’s desires and dignity even as it fought for its own preservation. Stories of their daring escapes highlighted their remarkable bravery and ingenuity, and photographs and sketches captured their humanity and the environments they navigated. Through their faith, bravery, and extensive networks, enslaved people carved paths toward their eventual freedom in refugee camps across the South.

When formerly enslaved people arrived at Union camps, Union officials were forced to grapple with their complicated legal status. They were not technically free, so the army had no right to keep them.

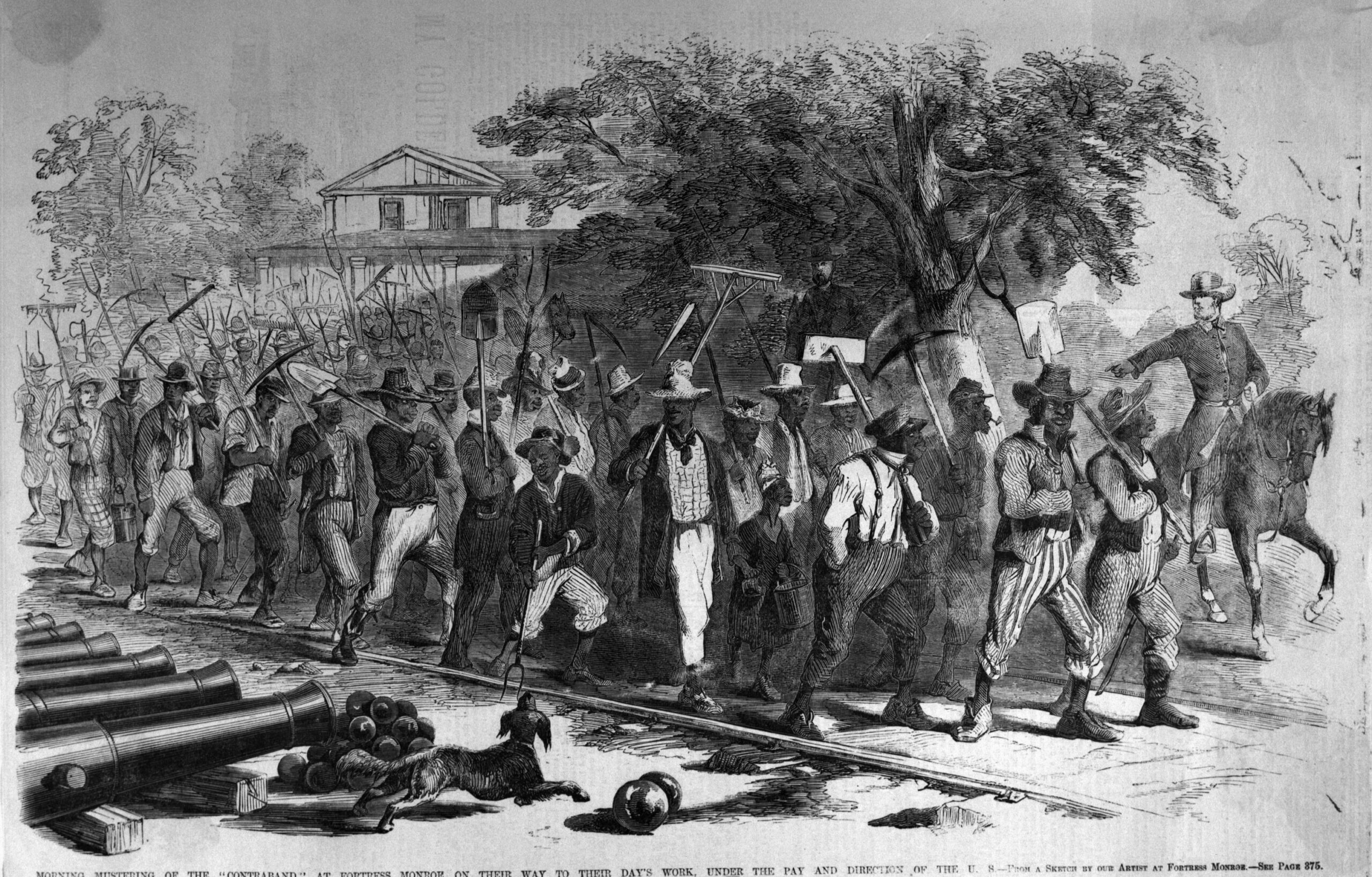

At Fortress Monroe, on the Chesapeake Bay, General Benjamin Butler devised a clever solution: runaways were declared “contraband of war.” As contraband, the Union Army claimed the formerly enslaved as property of a rebelling force. They established “contraband” camps to house freedpeople while they remained under the control of the army.

Eventually, federal legislation like the First and Second Confiscation Acts and the Militia Act of 1862 freed the enslaved who had escaped to Union Army camps from Confederate soldiers and planters. Many were conscripted into Union Army labor projects.

The illustration above depicts a group of Black laborers at Fortress Monroe who built military fortifications, raised encampments, and performed other labors. Black women worked in camps primarily as laundresses and cooks. Black men and women served as spies during the war, often moving between Union and Confederate camps. Black laborers often received no pay and worked under harsh conditions, facing abuse from Union army soldiers and missionaries.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

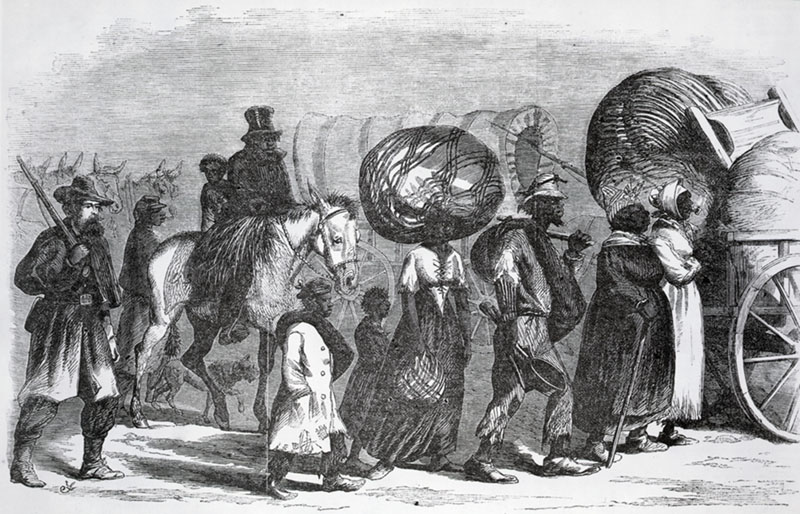

Enslaved people traversed streams, rivers, swamps, and forests to evade capture on their way toward Union Army campsites. The second sketch (above) depicts one journey of enslaved people toward Union lines during the Civil War. Some traveled regionally, just beyond the communities that they had known for years. Others traveled hundreds of miles across rough terrain to reconnect with family members in campsites. One group traveled over 750 miles from Alabama to eastern North Carolina.

Often families made several stops along their journey before settling in a contraband camp. Mary Barbour, a formerly enslaved woman from North Carolina, recalled her father waking her in the middle of the night to begin their perilous journey. Their family took a wagon from the mountains of McDowell County, North Carolina to the eastern region of the state. From there, they traveled to Roanoke Island, a refugee camp and small freedmen settlement where Union officials sheltered the wives of Black soldiers who served in the war.

Photo By Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

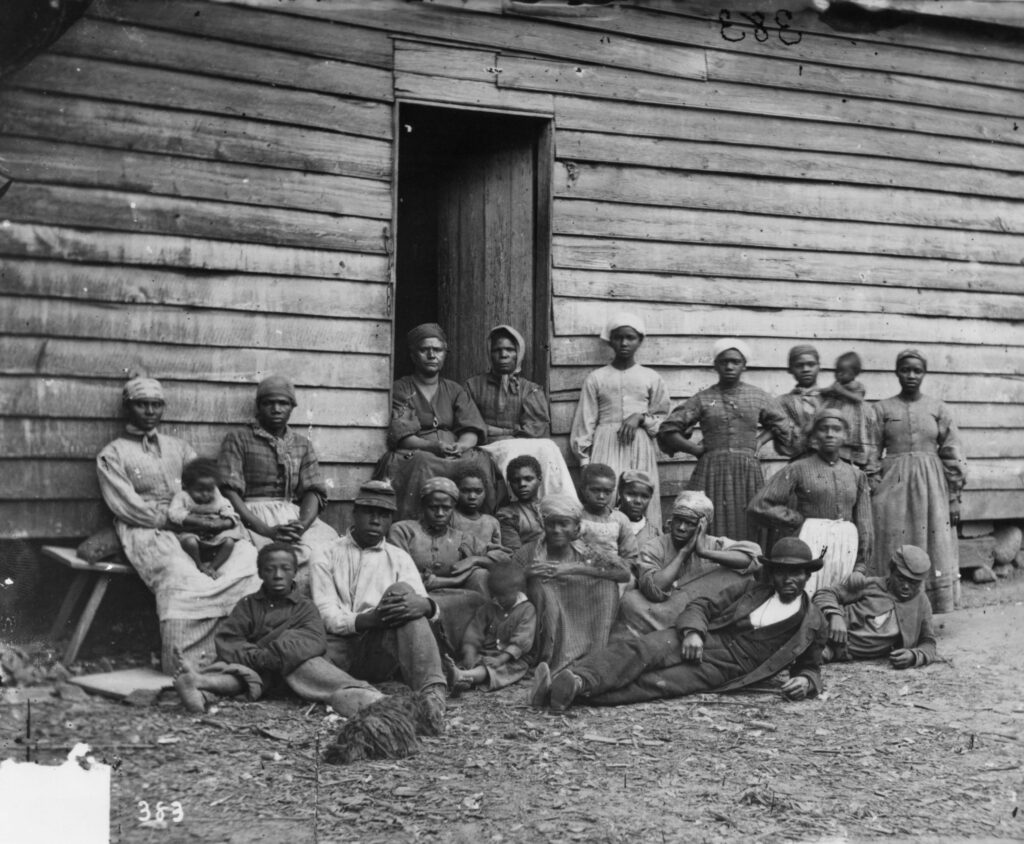

After the passage of the Emancipation Proclamation in January 1863, the Union Army recruited Black men for Civil War combat. In exchange for their service, the Union Army promised to care for their wives, children, and elderly in “contraband” camps and freedmen villages across the South.

Women, children, and the disabled maintained lives and developed communities in the chaos of war. In long-term contraband camps, freedpeople labored, crafted lives, and built schools and hospitals. Black women developed garden plots to supplement their diets and built homes for settlement after the war.

The photograph here captures the resiliency of Black women and children in refugee camps during the Civil War. Despite the ever-changing currents of the conflict, and the refusal of some Union soldiers, officials, and missionaries to acknowledge their humanity, freedpeople persisted.

Their bravery and audacity influenced generations as Black Americans continued to fight for freedom and self-determination throughout Emancipation, Reconstruction, and beyond.

Learn More:

Berlin, Ira, Barbara J. Fields, Steven F. Miller, Joseph P. Reidy, and Leslie Rowland. Slaves No More: Three Essays On Emancipation and the Civil War (1992).

Colyer, Vincent. Brief report of the services rendered by the freed people to the United States Army, in North Carolina, in the spring of 1862.

Glymph, Thavolia. “Invisible Disabilities”: Black Women in War and in Freedom,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society vol. 160, no. 3, September 2016.

Glymph, Thavolia. The Women’s Fight: The Civil War’s Battles for Home, Freedom, and Nation (2020).

Manning, Chandra. Troubled Refuge: Struggling for Freedom in the Civil War.

Murrell Taylor, Amy. Embattled Freedom: Journeys through the Civil War’s Slave Refugee Camps (UNC Press, 2018).