Photo by Heritage Images/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Perhaps no other person in the nineteenth century understood the power of photographs better than Frederick Douglass. The subject of some 160 images, Douglass used photography to transform the way Black Americans were viewed, helping to correct distortions of their portrayal and to reverse the “social death” institutional slavery caused.

After escaping slavery in 1838, Douglass was photographed and circulated his image widely over his remaining six decades of life. He believed that the power of photography could transform the perception of Black Americans.

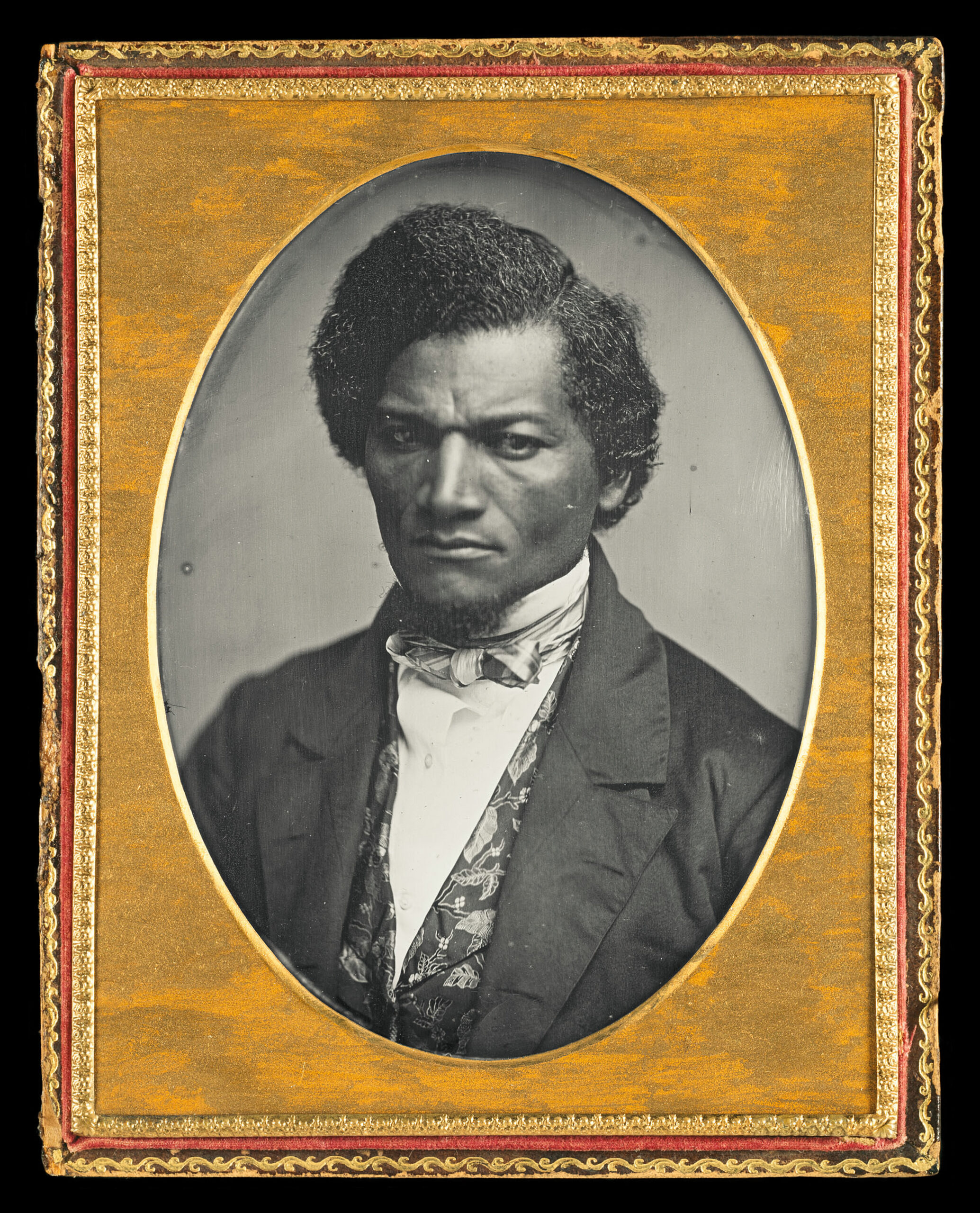

In 1847, when this portrait was taken, the stereotypical image of Black Americans was as dirty, uneducated, primitive laborers. The image was a deliberate visual challenge to such ideas.

Note his stern expression and his choice of dress. This was the same year that Douglass explained in a speech that he felt no patriotism for the United States. “What country have I?” he asked. “The Institutions of this Country,” meaning the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the government, “do not know me – do not recognize me as a man.”

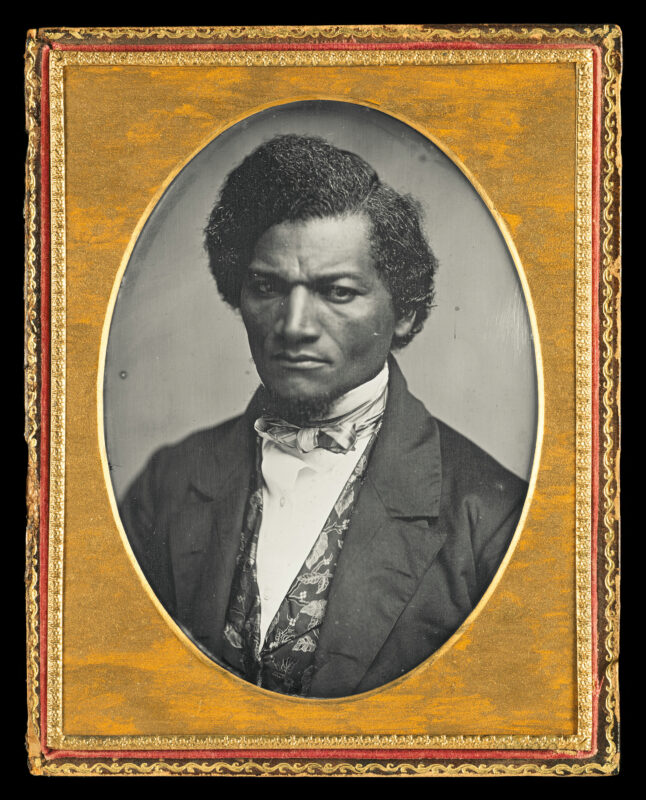

Eight years later, in 1855, Douglass had another daguerreotype portrait taken. Here his expression softened; his feelings about the United States, however, had not.

Photo by Heritage Images/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

In 1852, Douglass gave a speech in New York to the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society about the Fourth of July. “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July?” Douglass asked them. “I answer: a day that reveals to him… the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham.”

On December 3, 1861, seven months into the Civil War, Douglass spoke to a large crowd in Boston’s Tremont Temple about the democratizing power of photographic portraits. In his address, he admired how daguerreotypes had become so accessible that even “the humblest servant girl, whose income is but a few shillings per week, may now possess a more perfect likeness of herself than noble ladies and even royalty … could purchase fifty years ago.”

In comparing daguerreotypes to other art forms, he stated that “the picture and the ballad are alike, if not equally social forces—the one reaching and swaying the heart by the eye, and the other by the ear.” On the strength of photographic technology, he said “it is evident that the great cheapness and universality of pictures must exert a powerful, though silent influence upon the ideas and sentiment of present and future generations.”

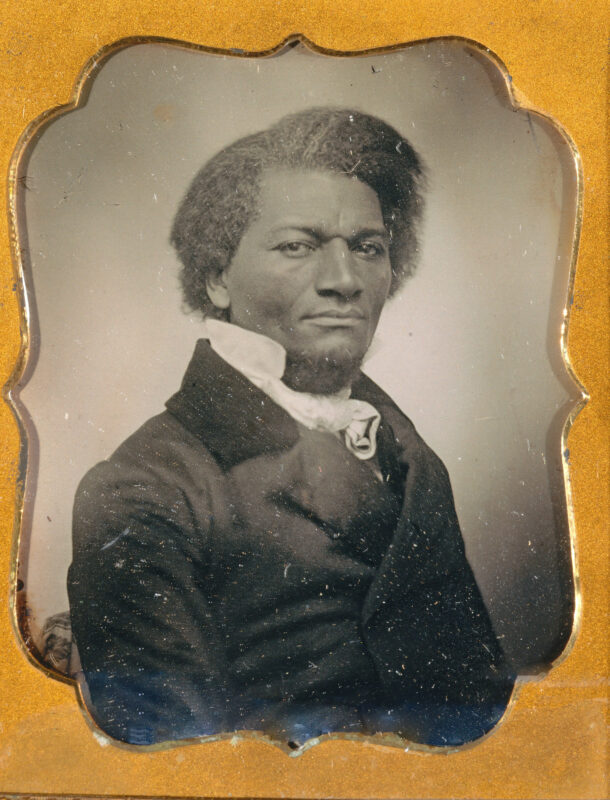

Almost two decades after his speech in Boston, Douglass still believed in the power of portraits, this time using tintype photography. This technology was similar to daguerreotypes but produced images more quickly and yet more cheaply.

Photo by MPI/Stringer/Archive Photos/Getty Images

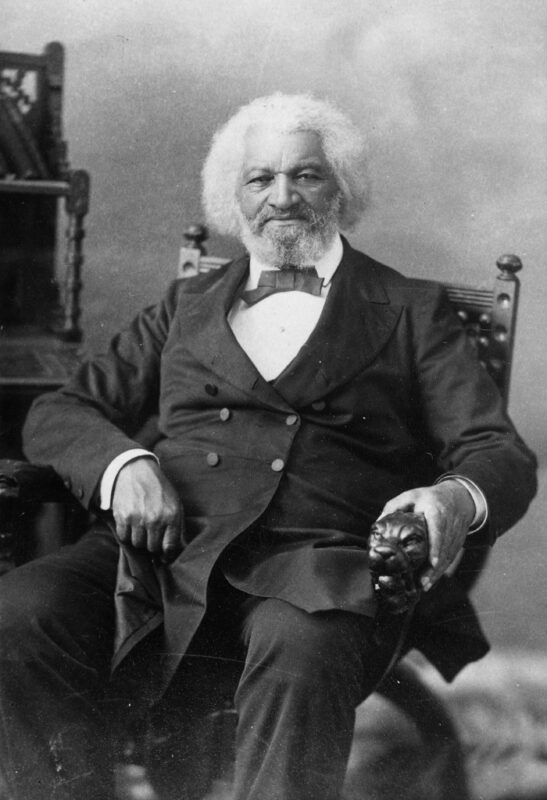

Taken in 1880, this image shows how Douglass had aged. His black hair and grown beard turned fully white, the wrinkles on his face deepened, and his suit reflected the style of the times. He seems to have put on some weight too.

Douglass had become an internationally renowned figure who remained an activist through the rise and fall of the Reconstruction Era. He capped his career by finishing his autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, a year later.

It is estimated that Douglass was photographed more than 160 times in his lifetime. Take a moment, then, to imagine the amount of time he spent posing in front of a camera. Early daguerreotype cameras took between three to fifteen minutes to capture a photograph. If the average exposure time for a daguerreotype was ten minutes, then Douglass would have spent a remarkable 1600 minutes, or over 26 hours, holding poses.

Although Douglass claimed he had his portrait taken over and over to change the portrayal of African Americans, he must have enjoyed doing it as well. His image came to stand for Black Americans in the second half of the nineteenth century, but he clearly wanted to preserve his own likeness as well.

Learn More:

Frederick Douglass. “Lecture on Pictures.” In Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American, edited by John Stauffer, Zoe Trodd, and Celeste-Marie Bernier, 129-130. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation: 2015.

Frederick Douglass National Historic Site. “Frederick Douglass and the Power of Photography.” Last modified August 19, 2022.

Library of Congress. “The Daguerreotype Medium.” Digital Collections, Daguerreotypes, Articles and Essays. Accessed March 22, 2023.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. “Frederick Douglass.” The Collection, Photographs. Accessed March 21, 2023.

University of Rochester. “Frederick Douglass Project: 5th of July Speech.” Accessed May 9, 2023.

Yale University. “Country, Conscience, and the Anti-Slavery Cause.” Accessed May 9, 2023.