Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images, Photo by Heritage Images/Getty Images, Photo by Archive Photos/Getty Images

Alicia Garza, Opal Tometi, and Patrisse Khan-Cullors founded #BlackLivesMatter in 2013. A year later, the African American Policy Forum initiated the #SayHerName campaign to highlight the gender-specific impact of racialized violence against Black women. Black women have always been at the forefront of social justice activism, calling attention to the intersectionality of their lives.

The three photographs here of Sojourner Truth, Anna Julia Cooper, and a banner of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs all show the binding threads of Black women’s self-representation, political analysis, and activist strategies. These are the same threads that continue to hold today’s movements together.

Black feminism—a social, political, and cultural movement that centers the lived experiences of Black women—has been an analytical tool of power relations as well as an activist strategy. Black feminism examines how the power structures and different forms of discrimination that shape Black women’s lives are entwined and strives to eliminate them.

We can look back to the 19th century to see the roots of ongoing debates, struggles, and strategies. In this history, we can trace Black women’s emerging collective consciousness, Black feminism’s first activists, and their controversial quests for respectability.

In 2021, the Black feminist theorist, activist, and educator Gloria Jean Watkins, better known as bell hooks, passed away. Forty years earlier, hooks’s book Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism analyzed Black women’s entwined discrimination through racism and sexism, perpetuated since the time of enslavement and mirrored in discrimination against Black women both in Black nationalism and white feminism.

The book’s title harked back to the first public expression of the distinct lived experiences of Black women in the United States: Sojourner Truth’s ad-hoc speech “Ain’t I a Woman?” at the 1851 Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio.

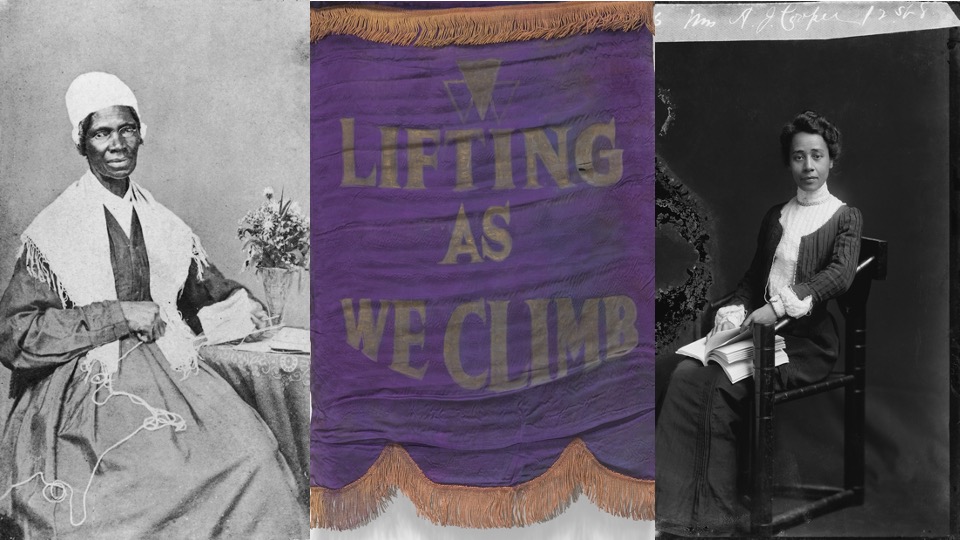

Truth (1797-1883) was a formerly enslaved woman who emancipated herself and became an abolitionist, suffragist, and civil and women’s rights activist. In Akron, she asked white suffragists to acknowledge Black women’s unique experiences of both racism and sexism that distinguished their lives from those of Black men and white women.

This 1864 portrait depicts a genteel Truth in a prim dress with a book and flowers on an end table and knitting in her lap. Truth models bourgeois, feminine respectability. The knitting, too, has significance: As a member of the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Massachusetts, Truth helped teach formerly enslaved people to make an independent living working with fiber.

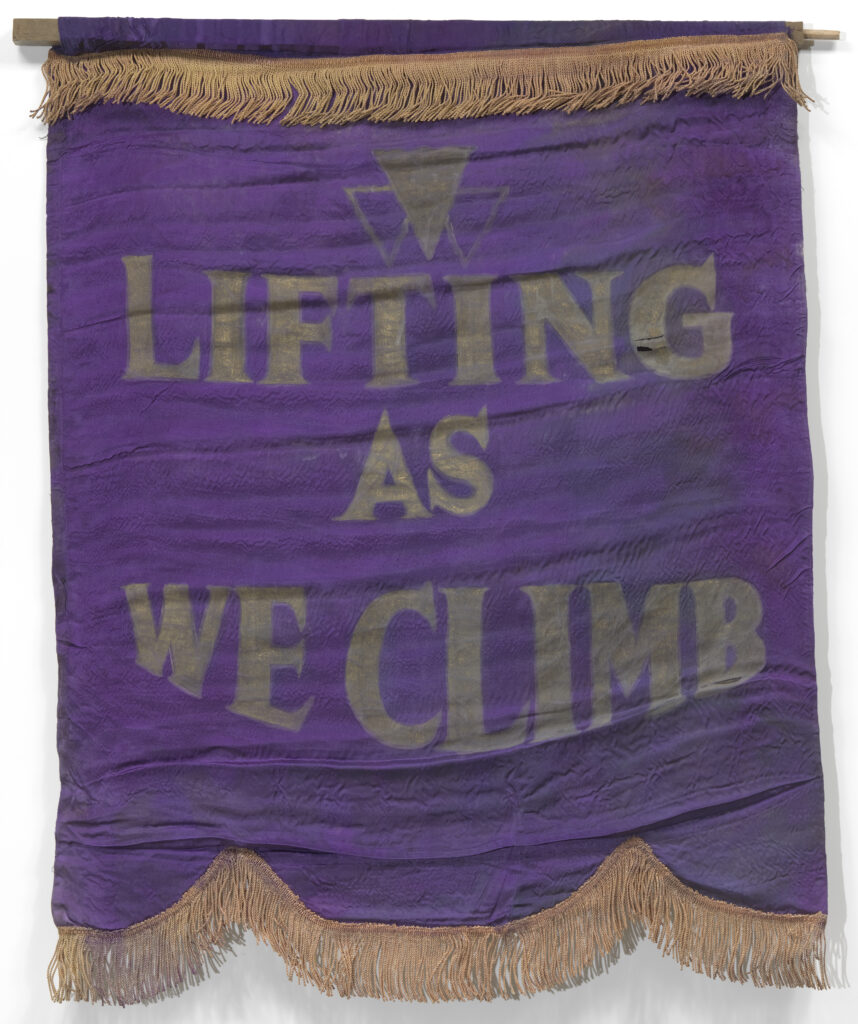

In this 1901 portrait, a well-dressed and coiffed Anna Julia Cooper sits with an open book in her lap, positioning herself as a scholar. At the turn of the century, Cooper indeed was one of the foremost Black feminist theorists and authors and the fourth African American woman in history to earn a Ph.D. (from the University of Paris, Sorbonne).

In 1892, she published her first book, A Voice from the South, which noted Sojourner Truth as an example of capable Black women, criticized white feminists such as Susan B. Anthony, and advocated for academic as well as industrial education for Black women.

In Cooper’s analysis, Black women faced discrimination both in Black, male-dominated organizations as well as in white ones and were subjected to unique dangers of exploitation. They hoped to “improve” Black communities through education, moral purity, and a Black upper class that would contradict anti-Black propaganda and lead Black communities to full citizenship.

With these aspirations in mind, Cooper co-founded the Colored Women’s League with fellow activists Ida B. Wells, Harriet Tubman, and Mary Church Terrell in 1892. Four years later, the Colored Women’s League and the Federation of Afro-American Women merged to form the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs (NACWC), commonly abbreviated as the National Association of Colored Women.

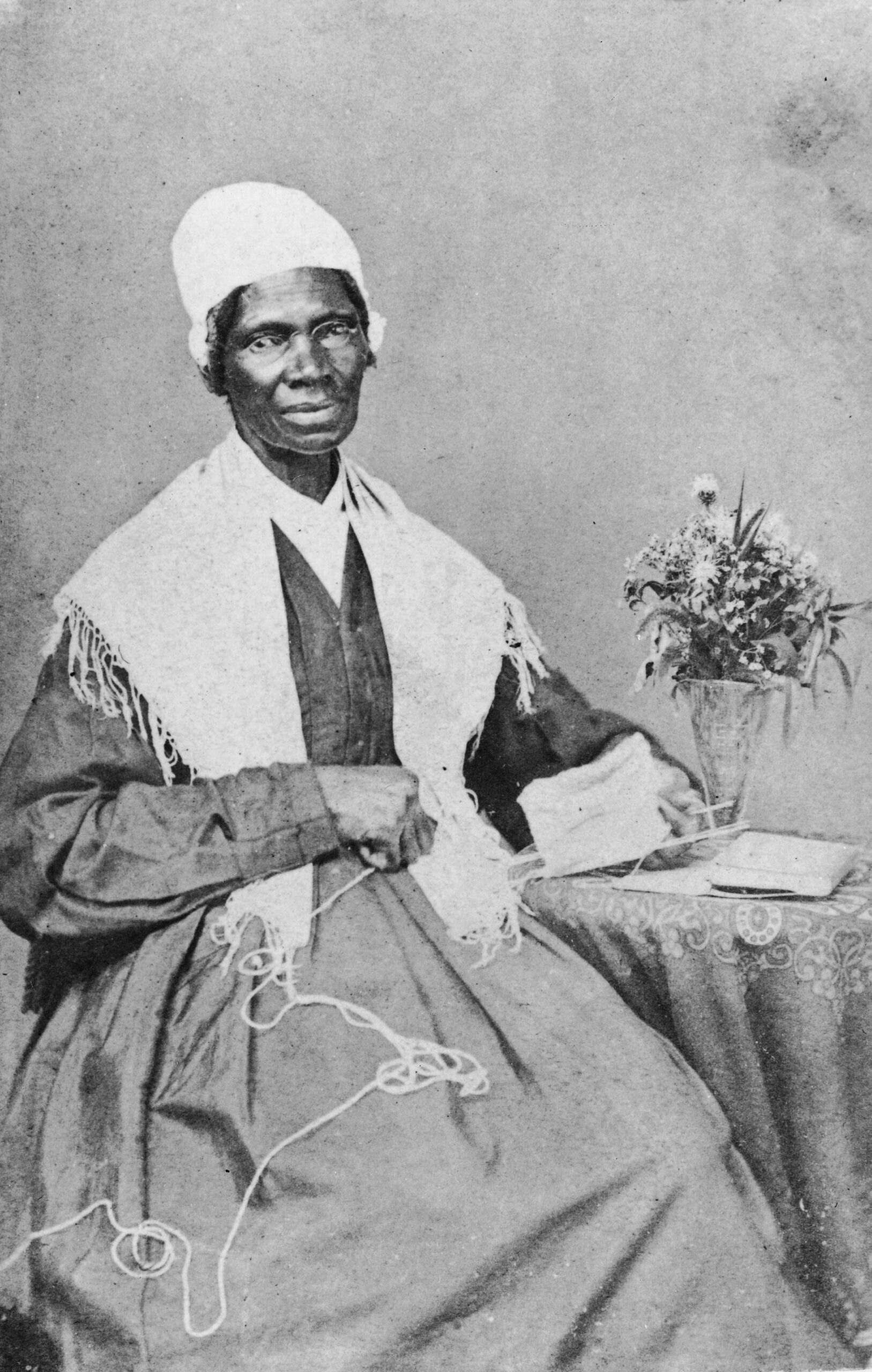

As the NACWC’s first president, Terrell addressed the National Women’s Suffrage Association’s convention in 1898. “And so, lifting as we climb, onward and upward we go, struggling and striving, and hoping that the buds and blossoms of our desires will burst into glorious fruition ‘ere long,” she proclaimed, expressing the NACWC’s motto that is emblazoned on this photograph of a banner used by one of the NACWC’s affiliate clubs in Oklahoma.

The banner’s colors, purple and gold, illustrated the club’s support of the women’s suffrage movement. “Lifting as we climb” signified not only the Black club women’s aspiration for Black self-empowerment and community progress, but also reflected the maternalism and elitism of respectability politics.

As middle- and upper-class, educated Black club women “climbed” above racist stereotypes, they hoped that their example as well as their supporting work would eventually “lift” all Black women to a higher status.

The NACWC focused on education, childcare, housing, healthcare, wage discrimination, and voting rights. They organized voter registration campaigns, fought against lynching, segregation, racist policing and imprisonment, and sponsored Black cultural events. Black women thus affected political change and, as bell hooks wrote about Black feminism many decades later, aimed to bring Black women from the margin to the center.

Black women’s activism centered many of the arenas, topics, and analyses of systemic forms and institutions of anti-Black racism that are still prominent in Black feminism today.

Learn More:

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. London/New York: Routledge, 2000.

Cooper, Brittney C. Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2017.

hooks, bell. Ain’t I a Woman?: Black women and feminism. Boston, Massachusetts: South End Press. 1981.