Photo by MPI/Getty Images

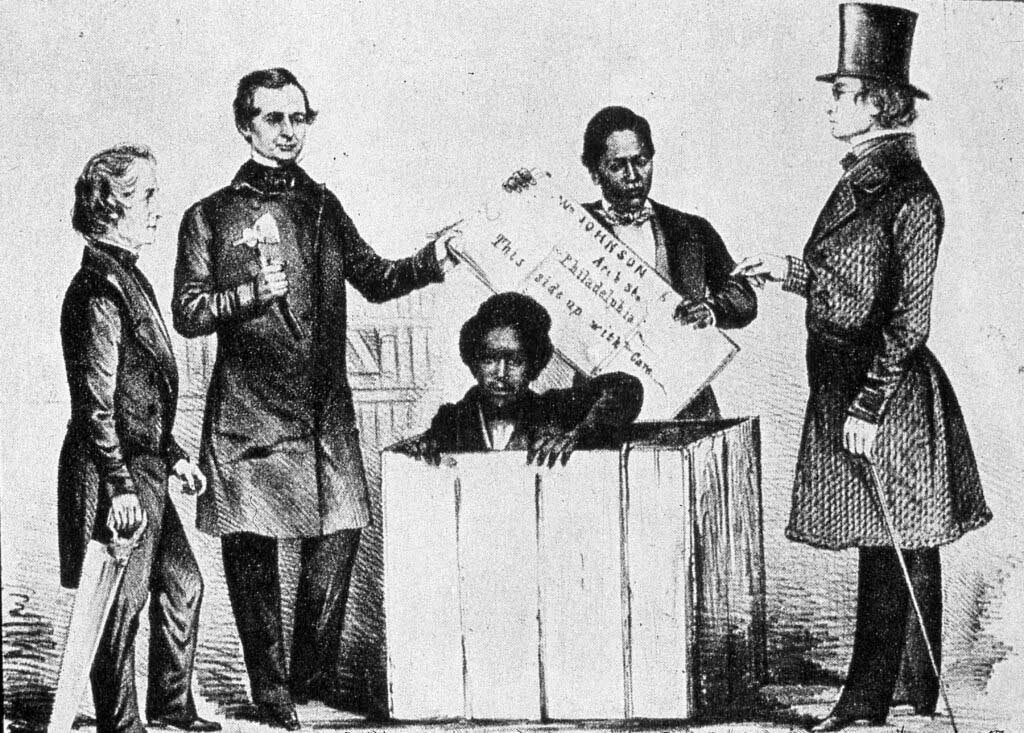

This lithograph, drawn around 1851 by Peter Kramer (1823-1907) and printed by Thomas Sinclair (1807-1881) of Philadelphia, was titled “The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown at Philadelphia.” William Still placed it at the top of the three-page prospectus he printed to advertise his book, The Underground Rail Road. The image was also included as an illustration to one of the book’s chapters, “The Resurrection of Henry Box Brown.”

Although Kramer’s image was not the first to illustrate the “unboxing” of Brown on Saturday, March 24, 1849, in Philadelphia, it is considered to be more accurate than an earlier depiction by Samuel Rowse printed in Boston in January 1850.

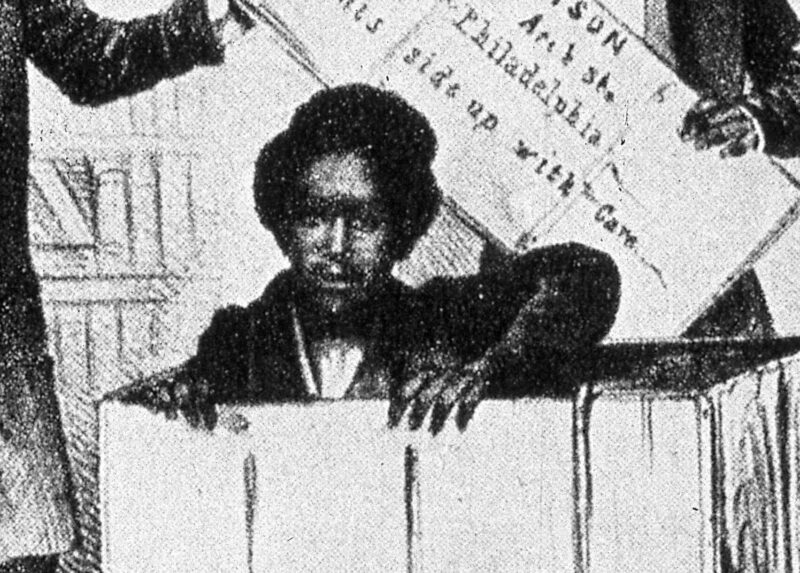

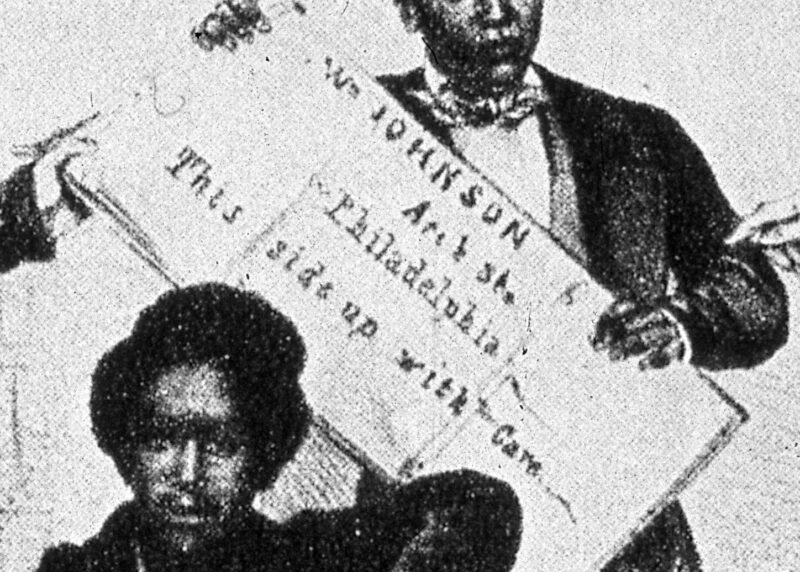

Kramer’s lithograph depicts the moment that Brown’s head and upper torso rose out of the crate, which had delivered him to freedom in Philadelphia after a death-defying 27-hour journey to escape from slavery in Richmond. He cheerfully greeted his four-member audience with the words “How do you do, gentlemen?” They were all pleased that their plan had succeeded and relieved that Brown survived the trip.

The four men who witnessed the dramatic moment of Brown’s emergence were the keenest of abolitionists. With the help of two allies in Richmond—Samuel A. Smith (c.1806- n.d.), a white sympathizer who was imprisoned later that year for “boxing up” two other slaves, and Brown’s friend, James C. A. Smith (fl. 1850), a free Black man—Brown traveled the 350-mile journey via the Adams’ Express, a private firm in Richmond. Brown took these desperate steps after his wife’s owner abruptly sold her and their children. The men are from left to right:

Lewis Thompson (1807-1866), who was part of the Philadelphia based publishing firm, Merrihew and Thompson, which published a variety of anti-slavery materials.

James Miller McKim (1810-1874), the publishing agent for the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society from 1840 to 1862 and later the general secretary for the Port Royal Freedmen’s Relief Association.

William Still (1821-1902), chairman of Philadelphia’s Vigilance Committee and father of the Underground Railroad. The notebooks and diaries he kept of his experiences helping nearly 800 slaves to freedom provide an invaluable record of the history of North American abolition and were later published.

Charles Dexter Cleveland (1802-1869), whose life-long dedication to the anti-slavery movement began as a student of Greek and Latin at Dartmouth College. He engaged in other initiatives, including an effort to free abolitionist Reverend Charles Torrey (1813-1846) from prison for “stealing slaves” in 1846.

Brown turned his ordeal into a money-making enterprise. He took his box to the stage and performed dramatic re-creations of his experience in the United States, the United Kingdom, and finally in Canada where he died in 1897. Brown’s audacity and dexterity as a true to life escape artist drew the attention of many, including Harry Houdini (1874-1926), whose collection of memorabilia about Brown is now in the Ransom Center at the University of Texas.

The image appeared again in 1976, when both Ebony (February and May 1976) and Black Enterprise (February and April 1976) carried advertisements celebrating Black History Month with a montage of famous Black freedom fighters that placed the portion of this lithograph showing Brown’s head and torso rising out of the box in the ad’s upper right corner to sell trips on United Airlines. “Fly the free skies of your land,” the advertisement declared and “celebrate freedom your way.”

In 2001, a reproduction of Kramer’s lithograph topped an orange and black advertisement for the Toyota Motor Company. Appearing in Jet (February 5 and 12, 2001), the text begins with the words “in 1849, the path to freedom was 3 feet x 2 feet” and concludes by saying that “[r]ecognizing those individuals who overcame great obstacles, Toyota joins in celebrating their strength.”

Twenty-first century viewers should be at once startled and dismayed to see the modern automobile and commercial jet liner equated to Brown’s packing crate by admen trying to sell travel to Black consumers. But on closer inspection, Brown’s life tells us that the type of vehicle used to make the journey he undertook was far less important than that it—and he—arrived at its intended destination intact.

Learn more:

Lerone Bennett, Jr., “Generation of Crisis,” Ebony (May 1962): 81-88.

Kathleen Chater, Henry Box Brown: From Slavery to Show Business (Jefferson, NC, McFarlane & Co., 2020).

Eric Colleary, Rare Ephemera Shows the Legacy of Henry “Box” Brown

https://sites.utexas.edu/ransomcentermagazine/2021/05/06/rare-ephemera-shows-legacy-of-henry-box-brown/

Martha Cutter, “Will the Real Henry ‘Box’ Brown Please Stand Up?” Commonplace: The Journal of Early American Life (Fall, 2015) https://commonplace.online/article/will-the-real-henry-box-brown-please-stand-up/

Michele Valerie Ronnick, “’Saintly Souls:’ White Teachers’ Instruction of Greek and Latin to African American Freedmen,” Free at Last! The Impact of Freed Slaves on the Roman Empire, eds. Teresa Ramsby and Sinclair Bell, (London: Gerald Duckworth & Co., 2011): 177-208.

Historical Society of Pennsylvania, William Still’s Prospectus

https://hsp.org/sites/default/files/xam1873still-13744-q.pdf

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins Resurrection, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=O5MR_e7HRIM

Screamin’ Jay Hawkins on Arsenio Hall with Emo Philips, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3S7a4Uj2yME

William Still, The Underground Rail Road (Philadelphia, Porter & Coates, 1872).