Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

On January 7, 1973, Mark Essex, a twenty-three-year-old Black Navy veteran from Emporia, Kansas, was shot and killed by police on the rooftop of the Howard Johnson’s Motor Lodge in downtown New Orleans. His body lay dead, riddled with more than 200 bullet wounds, as a dark smoke cloud filled the air from the top floor of the burning hotel. Quite literally, the roof was on fire.

A series of shootings by Essex, beginning on the night of December 31, 1972, and ending with his rooftop execution, left nine others dead and twelve people wounded. Most of these were white police officers. Essex came to be known as the New Orleans Sniper.

Three days after the Howard Johnson’s showdown, police discovered Essex’s last known residence at 2619½ Dryades Street, an apartment in the predominantly Black Central City neighborhood.

While stationed at Imperial Beach Naval Base in California in the late 1960s and early 1970s, Essex had experienced racist harassment by white petty officers on base and white police officers off base. As a result, he drew closer to fellow Black sailors with militant attitudes including one from New Orleans. Essex moved to New Orleans in summer 1972 to try and reconnect with this friend. He continued to witness police brutality inflicted on Black people.

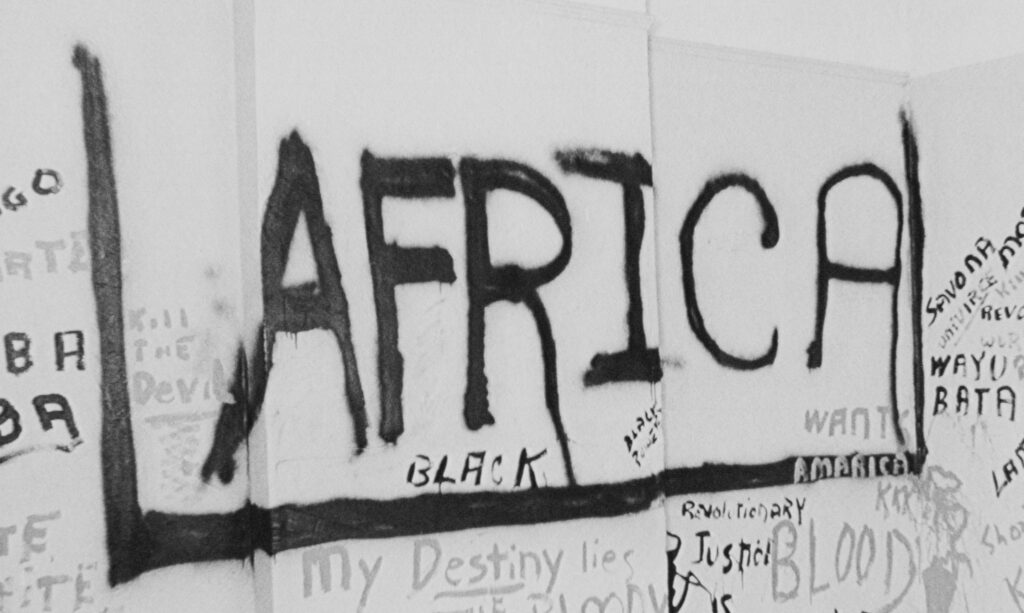

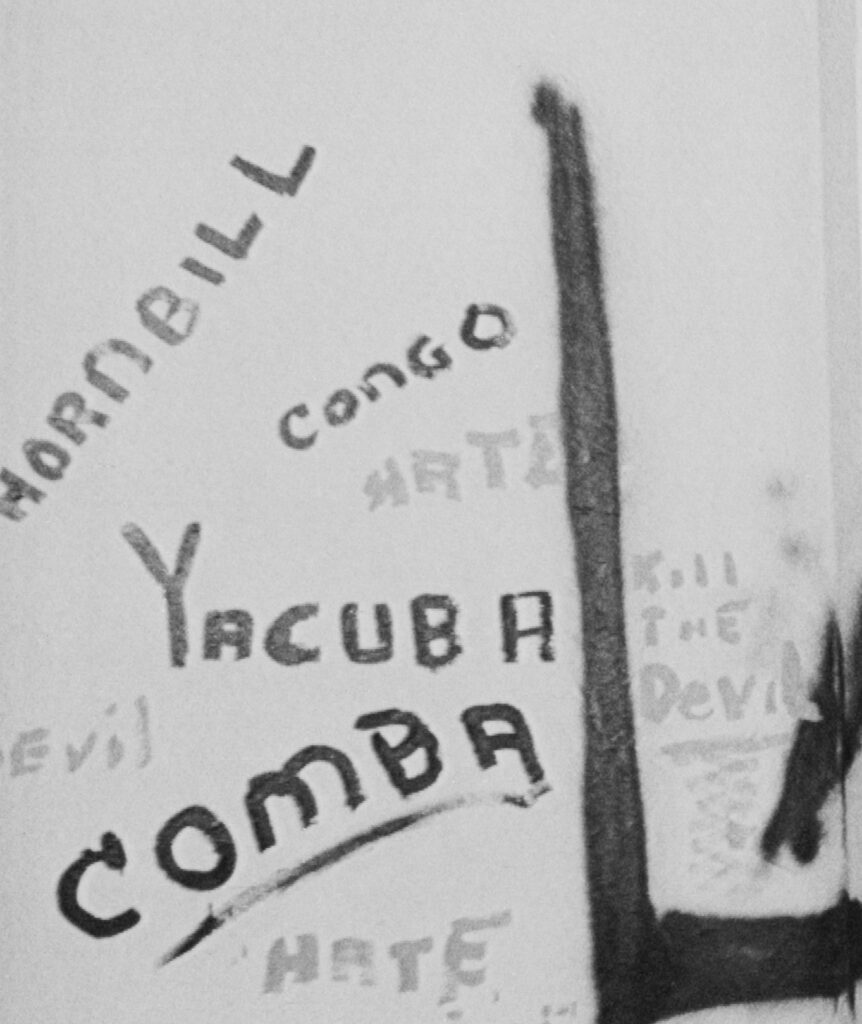

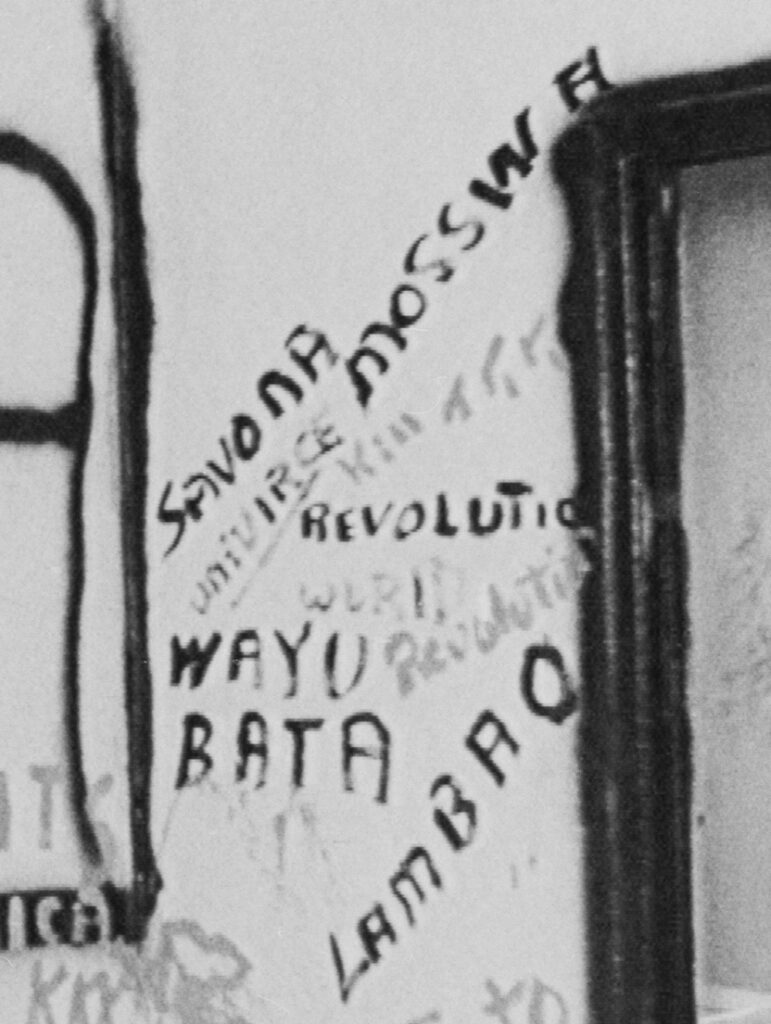

Police found his apartment in a state of disarray: a leaking waterbed, greasy floors, broken baseboards, empty juice bottles, disheveled books and periodicals, and charred pieces of paper. But the general condition of the place was accented by painted scribblings on the walls.

This photograph gives us a peek inside that apartment. The viewer’s eye is likely drawn first to “AFRICA.” Painted in black letters inside of a boxed border of the same color, its enormous size and position suggest it is more central to Essex’s thinking than the other words and ideas painted on the wall.

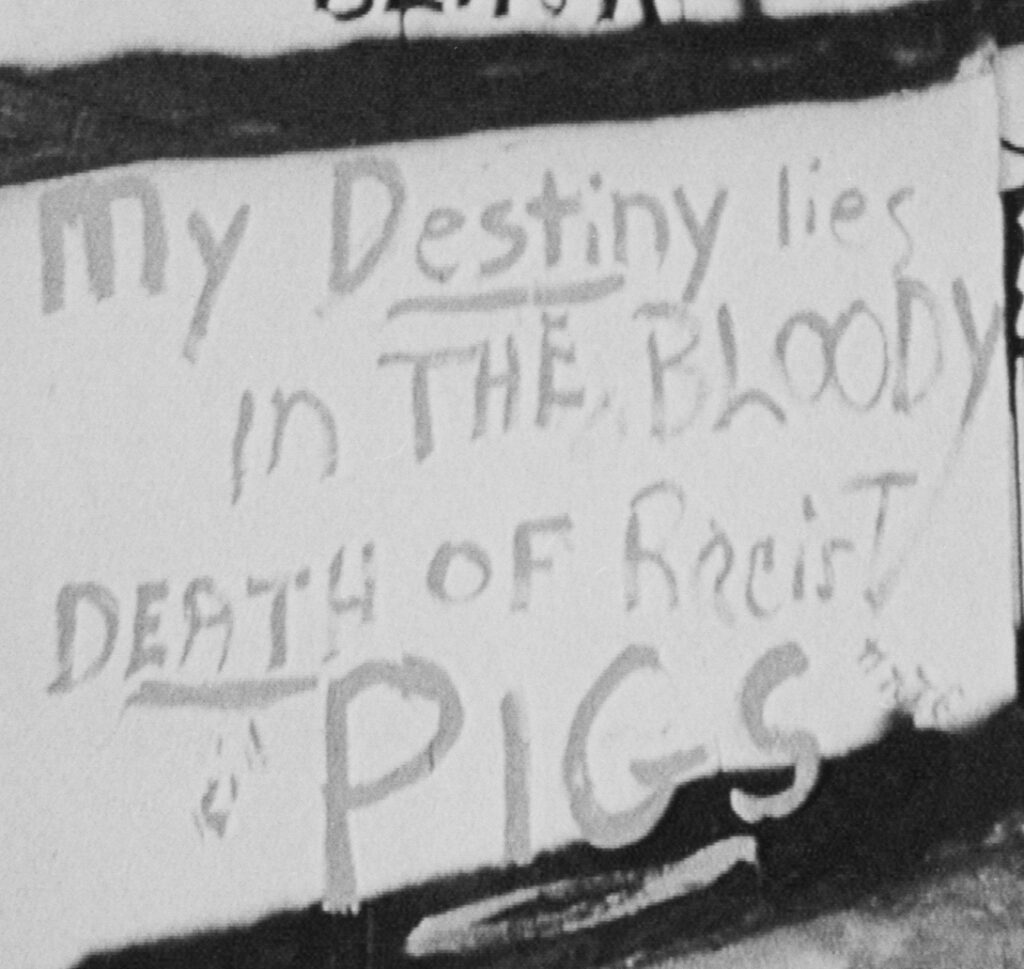

The prefix “AFRI” surges forward on a protruding wall and is underscored by the word “BLACK.” Invisible in the photograph, Essex penciled inside the giant letter C, “The quest for freedom is death—then by death I shall escape to freedom.” This vision, then, is directly linked to the red-painted message beneath it: “My Destiny lies in THE BLOODY DEATH OF Racist PIGS.” Reporters, police officers, and community members were immediately drawn to this particular message because of its prophetic nature.

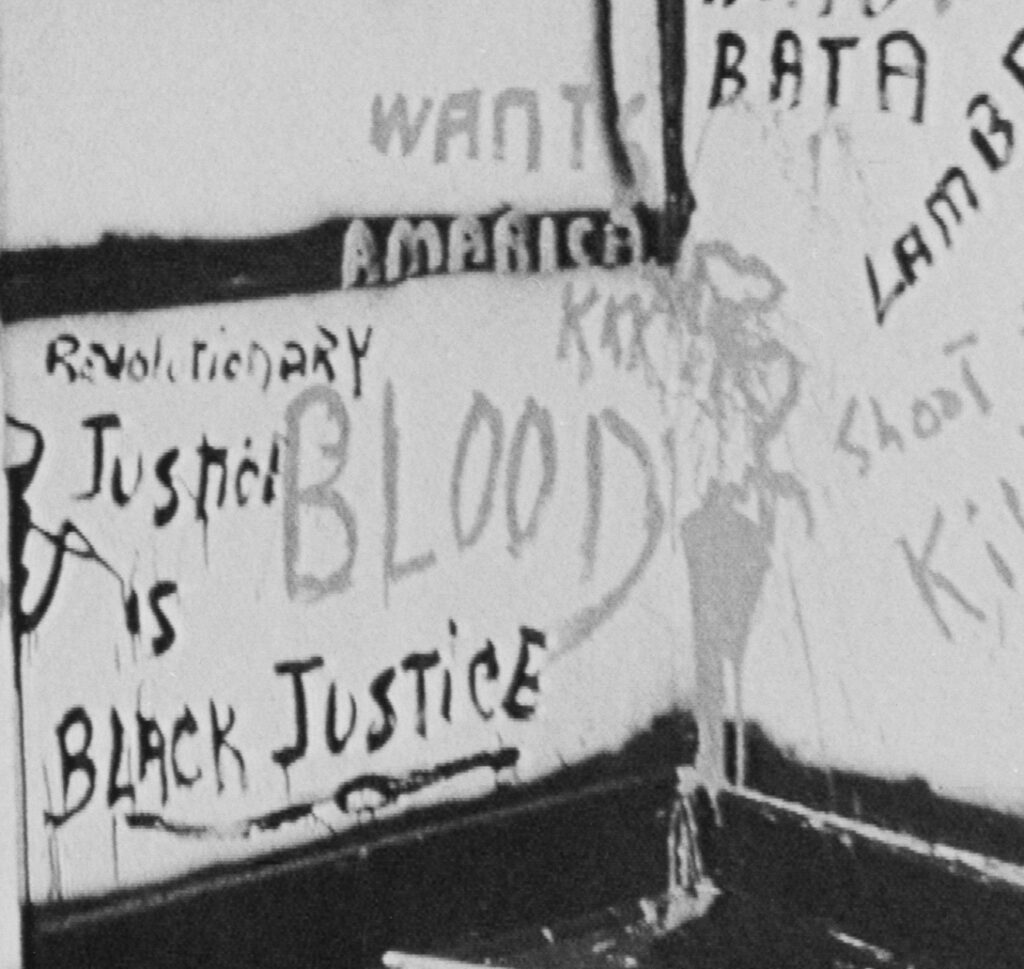

On the immediate outskirts of the black frame, we see various English and Swahili words—some misspelled—referencing war, battle, revolution, and justice. Some of these words appeared in two letters that Essex sent before the shootings began: one to his mother in Emporia, Kansas; another to a local news station in New Orleans.

In both, Essex opens with “Africa,” as in “Africa greets you,” or “Africa, this is it mom.” He also signs them “Mata”—one of the words found painted on his apartment wall, which a Swahili language expert translated as “a native shooting weapon.”

In the letter to WWLTV, Essex notes, “The death of two inocent [sic] Brothers will be avenged. And many others.” Less than two months before the New Orleans shootings, white police officers had killed two Black students on the campus of Southern University in nearby Baton Rouge.

Alarmed neighbors gathered in the apartment days after the police’s discovery. While the local Black community might not have identified with the “New Orleans Sniper,” many recognized him through his torturous writings on the wall. His rhetorical rage reminded them of younger brothers and cousins who spoke with a similar disdain for white people. While they initially saw Essex as “crazy,” the familiarity with his written ideas complicated their reactions.

Much has been written about Essex—his mental state, his presumed organizational affiliation with the Black Panthers, and even his encounters with racial prejudice. But what do his writings reveal?

His message—in both of his final letters and especially in the painted words on his apartment walls—reveals a militant commitment to defending the Black community from white brutality. The writings on the wall made it harder to dismiss his legitimate rage. Instead, in 1973, Black and white New Orleans was forced to grapple with his thoughts on race and resentment, not just the shootings.

Learn more:

William Earl Berry, “The Navy Did This to Him,” Jet (February 1, 1973).

Danny Cherry Jr., “Mark Essex: The Fires We Ignore,” Antigravity (May 2022).

Peter Hernon, A Terrible Thunder: The Story of the New Orleans Sniper (New York: Doubleday, 1978).

Leonard Moore, Black Rage in New Orleans: Police Brutality and African American Activism from World War II to Hurricane Katrina (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2010).

New Orleans Police Department, “Official Report on the Mark Essex Shootings” (August 31, 1973).