Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

A Pulitzer Prize winner hailed as a literary masterpiece, Toni Morrison’s Beloved has also been the subject of repeated censorship, revealing the ongoing tension between its critical acclaim and the discomfort it causes in confronting the history of slavery, Black resistance, and the painful legacies of racial trauma.

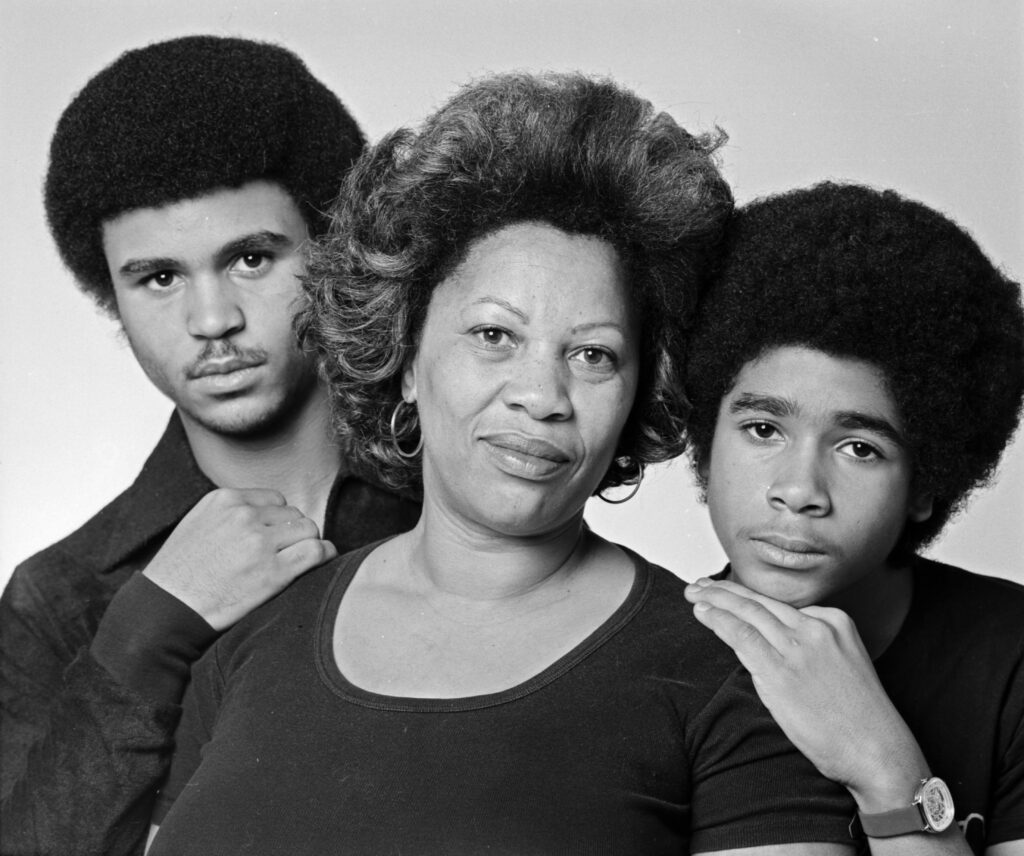

When Morrison, seen here in 1985, published Beloved in 1987, it instantly captivated both popular audiences and the literary world. Morrison’s fifth novel, today Beloved appears in more than 1,500 syllabi and is central to some 1,000 scholarly works. Morrison is one of the most-read women writers in universities in the United States, Canada, and Australia.

At the same time, Morrison’s work has been a target for censorship. In 2016, Virginia state Sen. Richard Black called Beloved “vile” and “profoundly filthy […] moral sewage.”

In fact, The American Library Association (ALA) frequently includes Morrison’s books on its Top 10 Most Challenged Books list. Beloved appeared in 2006 and 2012, and The Bluest Eye was listed in 2006, 2013, 2014, 2020, and 2023. The ALA reports that book bans are increasing.

Dana A. Williams, president of the Toni Morrison Society, argues that Morrison is singled out because “Blackness is the center of the universe for her and for her readers,” which some audiences consider inappropriate.

Morrison presents Black characters as fully realized individuals, unsettling those who expect Black experiences to be framed through whiteness. The backlash—censorship, bans, accusations of obscenity—shows that even mainstream recognition cannot shield her work from those who find it threatening.

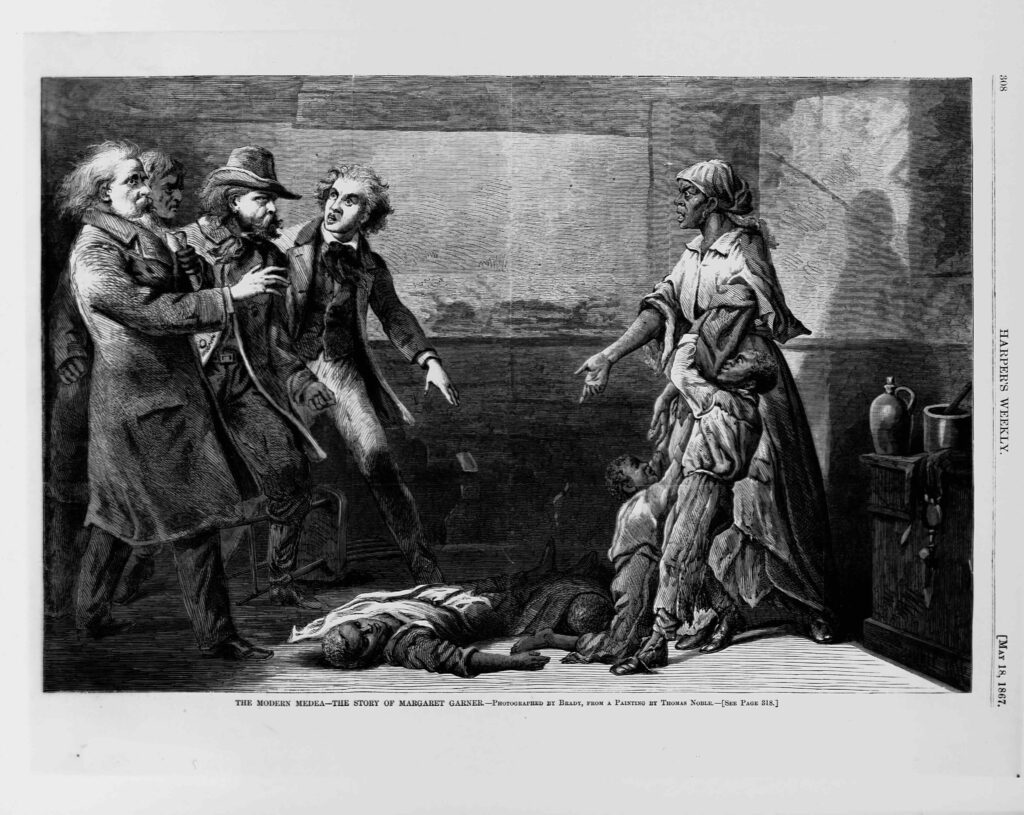

Morrison was inspired by Margaret Garner, an enslaved woman who tried to escape with her family. On a frozen January night in 1856, they fled a Kentucky plantation and crossed the Ohio River into Cincinnati, seen here in 1848. Ohio was a free state, but the Garners were pursued and caught.

Photo by Fotosearch/Getty Images

Archibald Gaines and Thomas Marshall obtained a warrant under the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act and, with U.S. marshals, attempted to reclaim the Garners—not as people, but as property. The family resisted.

Margaret, knowing they would all be enslaved again, killed her 2-year-old daughter, Mary, and attempted to kill the rest of her children before being stopped. Margaret later said she would rather her children “go home to God than back to slavery.”

Instead of being tried for murder, she was indicted for destruction of property. She was found guilty and forced back into enslavement with her family. This wood engraving dramatizes Garner confronting her pursuers. She stands defiantly over two of her dead children as the other two cling to her skirt.

Photo by Library of Congress/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

In Beloved, Morrison keeps “the essence” of Margaret’s bold act. Sethe, like Margaret, resists slavery’s control over her body and her children’s futures.

This relates to what Ta-Nehisi Coates called “the system that makes your body breakable.” Parents who inflict pain do so to shield their children from a world that would harm them even more. Sethe says, “The best thing she was, was her children. Whites might dirty her all right, but not her best thing, her beautiful, magical best thing.”

In 1987, Morrison told Alan Benson, “For me, it was the ultimate gesture of the loving mother. It was also the outrageous claim of a slave. The last thing a slave woman owns is her children.”

Margaret’s daughter, Mary, was “nearly white” and may have been Archibald Gaines’ child through rape, a common reality for enslaved Black women. Margaret herself was described at the time as “mulatto.” To Gaines, Margaret did not own Mary—he did. Unlike Margaret, Sethe goes on to live a free life.

Photo by Jack Mitchell/Getty Images

Morrison, pictured here with her sons, was clear that Beloved is not about slavery itself but about “what happens internally, emotionally, psychologically, when you are in fact enslaved and what you do to try to transcend that circumstance.” She described the novel as focusing on “the interior life of […] a small group of people, and everything that they do is impacted on by the horror of slavery, but they are also people.”

In 1988 Beloved won the Pulitzer Prize, though not the National Book Award. But on October 8, 1993, 23 years after her first published book, Morrison won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Among the four Black writers who have won the Nobel Prize in literature, Morrison remains the only woman.

Prize prestige shapes which books are read and which authors are revered, but it does not protect them from censorship. Harlem Renaissance poet Langston Hughes wrote, “We Negro writers, just by being Black have been on the blacklist all our lives […] Censorship for us begins at the color lines.”

The fact that Morrison’s books are so often challenged proves that the stories they tell successfully undermine American misunderstandings about Black history.

And while banning Morrison’s books have been futile attempts to silence her distinctive voice, she told the audience at the Nobel banquet on December 10, 1993, that she – and we – wait “in joyful anticipation of [the] writers to come.”

Learn More:

Toni Morrison. Beloved.

Toni Morrison. Burn This Book: PEN Writers Speak Out on the Power of the Word.

Toni Morrison. The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations.

James F. English. The Economy of Prestige.

Percival Everett. Erasure.

Timothy Greenfield-Sanders. Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am.

Alexander Manshel. Writing Backwards: Historical Fiction and the Reshaping of the American Canon.

Mark Reinhardt. Who Speaks for Margaret Garner?

Richard Jean So. Redlining Culture: A Data History of Racial Inequality and Postwar Fiction.

Nikki M. Taylor. Driven Toward Madness: The Fugitive Slave Margaret Garner and Tragedy on the Ohio.

‘Who Cares about Literary Prizes?” by Alexander Manshel, Laura B. McGrath, & J. D. Porter

“Toni Morrison, In Her New Novel, Defends Women” by Mervyn Rothstein

“Margaret Garner’s story has resonated for the past 164 years. It’s one she never got to tell” by Sarah Haselhorst

“Margaret Garner, Rememory, and the Infinite Past: History in Beloved” by Kristine Yohe

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

Overlooked: Margaret Garner by Rebecca Carroll

A Mother’s Desperate Act: ‘Margaret Garner’ by Bruce Scott

48 Black Writers Protest By Praising Morrison By Edwin McDowell

Black Writers in Praise of Toni Morrison

What 35 Years of Data Can Tell Us About Who Will Win The National Book Award

Divided Shelby school board lifts ban on book by Lynn Moore

Toni Morrison defends ‘sacredness’ of books against censorship by Alison Flood

Black Literature Day: Re-Discovering Beloved by Toni Morrison by Whitney Greyton