Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

Driving across Georgia in August 1960, eleven students from Atlanta’s Morehouse College passed the time singing “Wade in the Water,” an African American spiritual said to have been sung by Harriet Tubman on the Underground Railroad. It was a long drive to Savannah, where they planned to wade into the water off the coast of Tybee Island to desegregate the beach.

Inspired by the success of recent lunch counter sit-ins, African American activists organized wade-ins along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts throughout the early 1960s. In Savannah, the white population assailed them with racial slurs until police escorted them to jail. African Americans continued to stage wade-ins in Savannah for the next two summers, finally forcing the city to desegregate the beach in 1963.

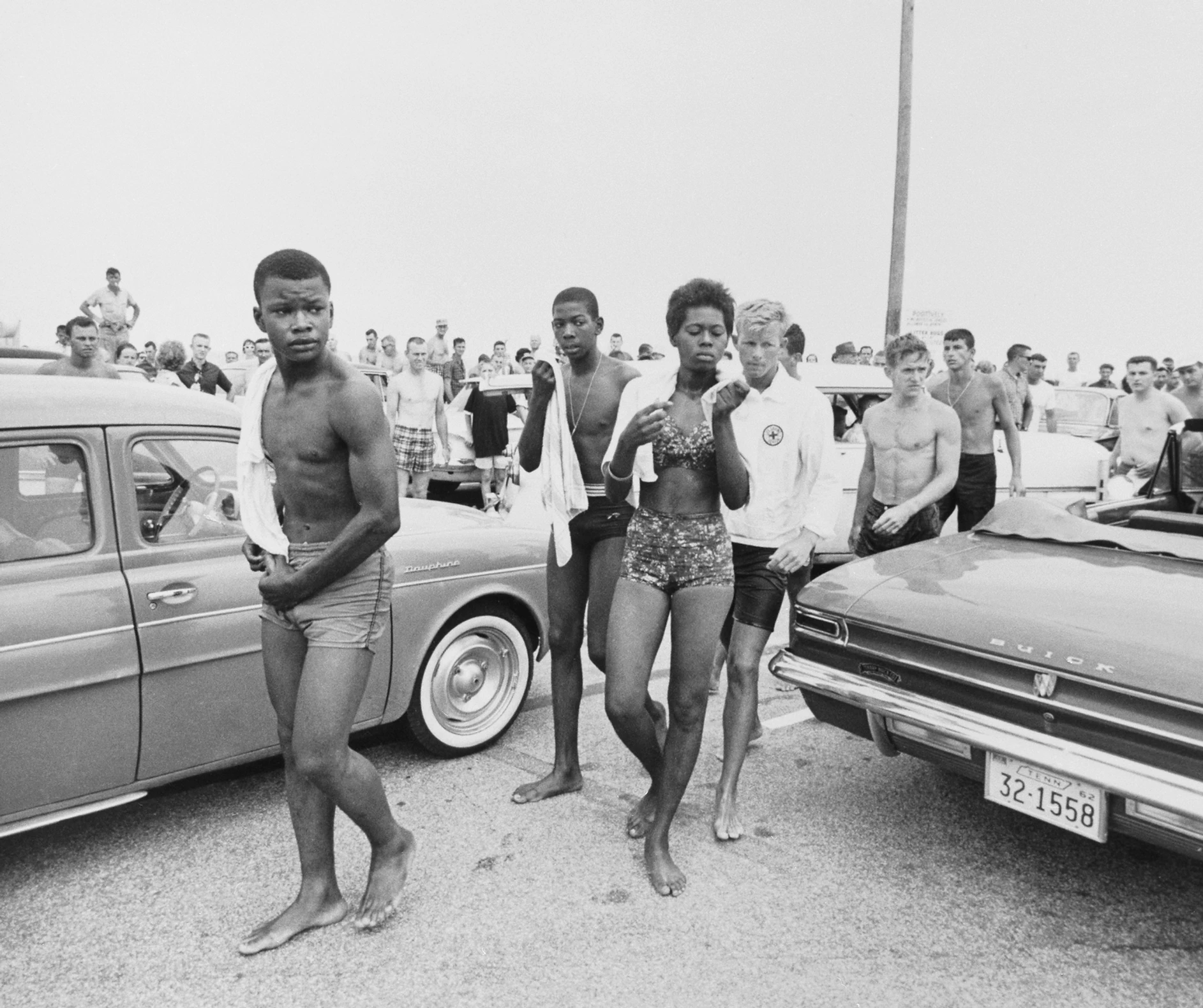

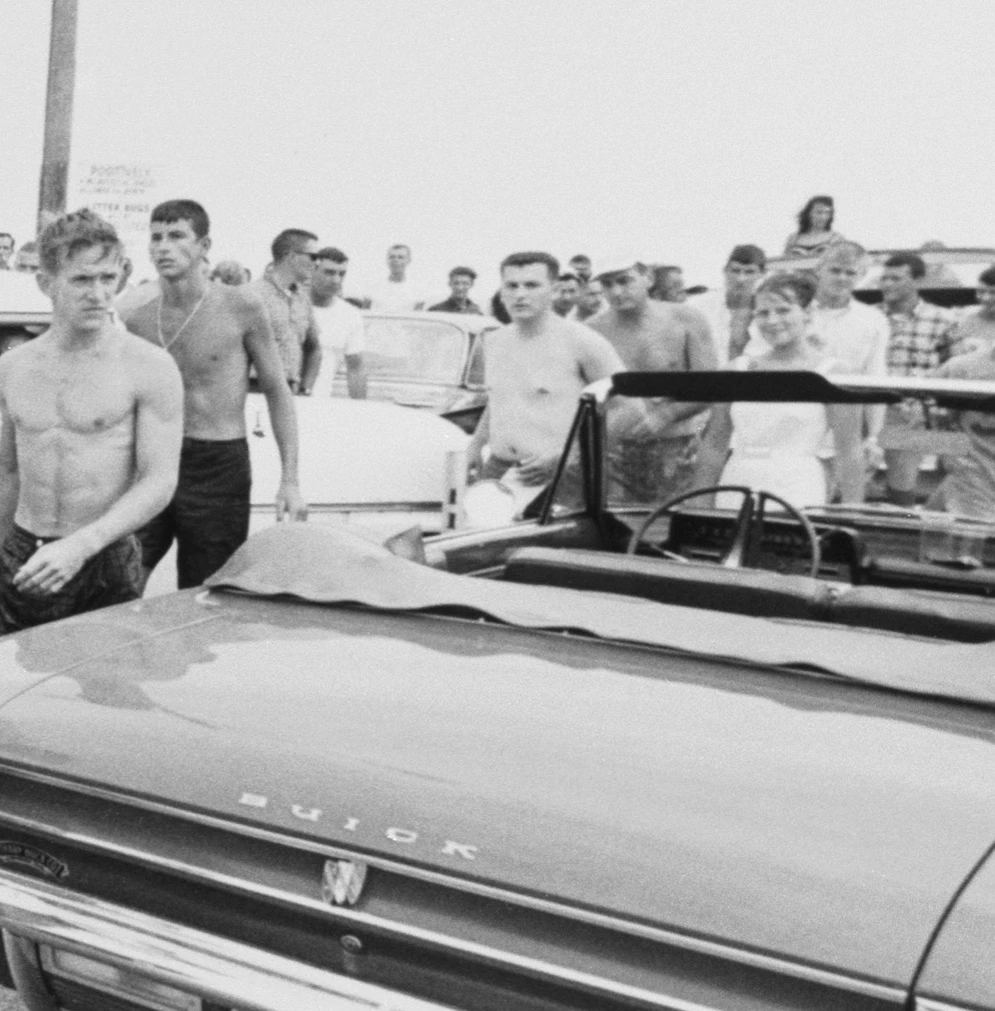

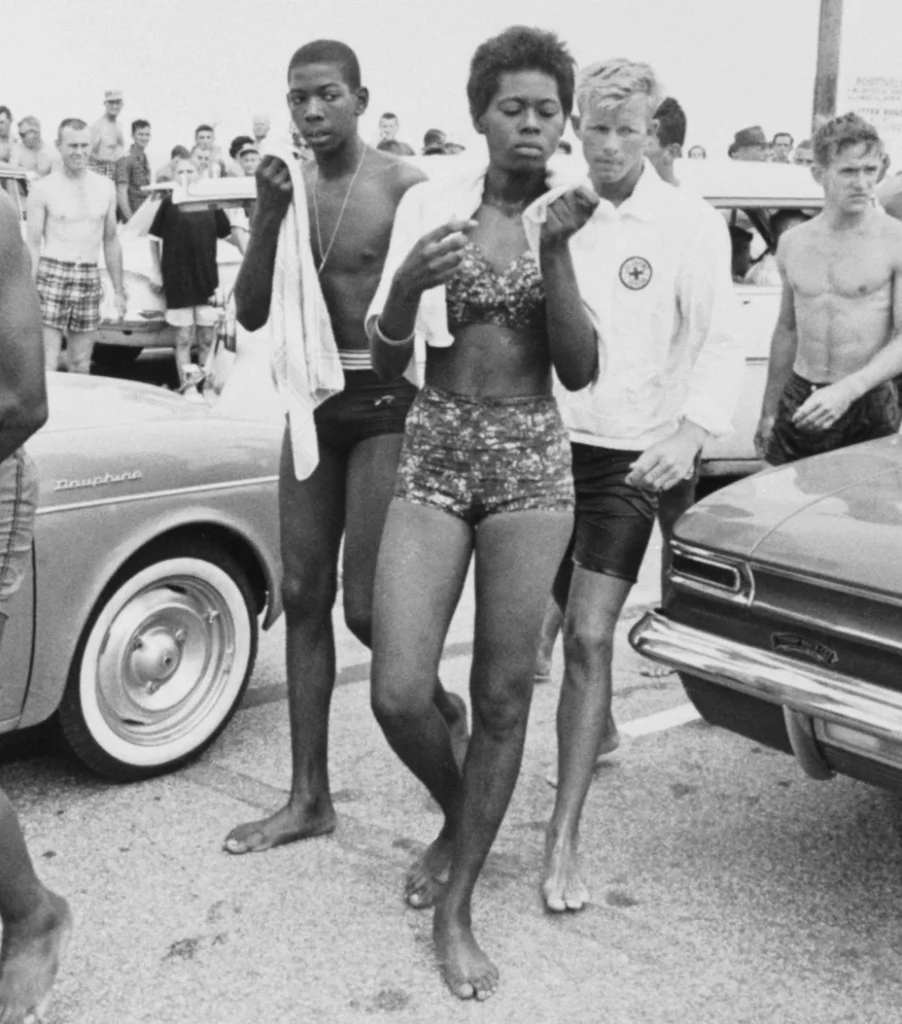

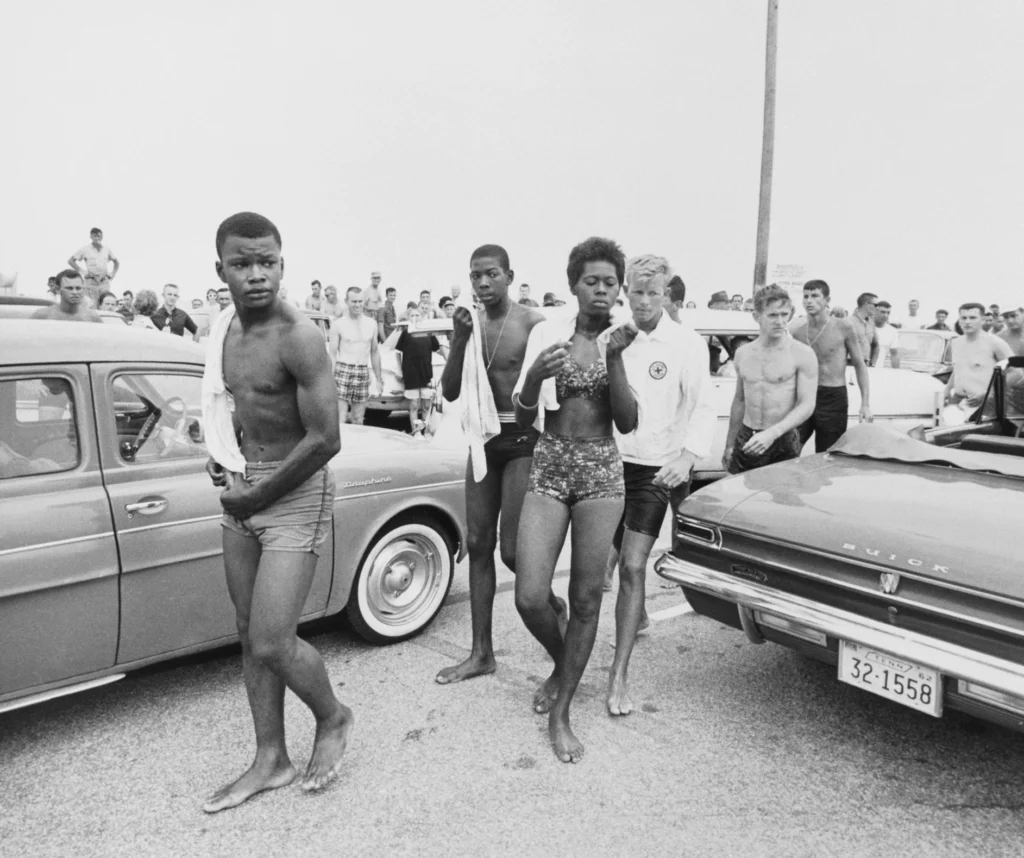

Photographs of this wade-in highlight the complexities of the Black Freedom Struggle and Jim Crow segregation. The mob’s anger reveals how the struggle for leisure and access to nature accompanied those for voting rights and economic freedom. For whites, upholding a segregated landscape and regulating the sexuality of the activists’ semi-nude bodies were paramount.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

In the photograph above, Savannah’s white beachgoers exhibited a range of emotions from anger to glee as they flanked and outnumbered the young African Americans they drove off the beach. The state’s involvement in Jim Crow segregation is also on full display as local police officers escorted the activists to jail. Such unified opposition reveals just how strongly the white population and local government did not want African Americans to enjoy Savannah Beach.

Civil rights activists in the early 1960s fought to integrate spaces like buses and lunch counters, each integral to daily life, but they also maintained that African Americans deserved equal access to leisure and recreation. Summer days at the beach were a part of life in Savannah and other coastal cities, and activists considered wade-ins central to their wider struggle.

The rows of cars lining the beach remind us of the important role that mobility played to the Black Freedom Struggle, and specifically to the environmental injustices plaguing Savannah. The nearest beach to which African Americans had access was in Hilton Head, South Carolina, about twice the distance from downtown Savannah as Tybee Island. Driving was never completely safe for African Americans, but the longer journey made going to the beach that much more dangerous and inaccessible.

Beaches and other natural spaces provided a much-needed place for southerners to cool off during the summer. Excluded from beaches, African American children often swam in streams polluted by industry or parks overcome with runoff, contributing to disproportionately higher death rates. Desegregating the natural spaces of Savannah Beach represented a step toward greater access to relaxation and environmental justice.

Dressed only in swim trunks and bikinis, the bodies of male and female activists drew the ire of white beachgoers and provide the focal point of both photographs. White anxiety regarding interracial sexuality played a central role in upholding segregation.

Whites maintained stereotypes of Black men as sexual predators preying on white women, whom they considered emblematic of racial purity. They cast Black women as sexually promiscuous figures who took advantage of white men. More than anything, they feared interracial sex and marriage. At Tybee Island and other beaches, these threats became terrifyingly real with the risk of white and Black bodies intermingling daily.

Singing “Wade in the Water” as they fought to desegregate Savannah Beach, these young activists participated in a struggle for freedom that reached back to the eighteenth century. The beach had been there before anyone, white or Black.

When slave traders first brought West Africans to Georgia in the eighteenth century, Tybee Island served as a quarantine station. Following the treacherous Middle Passage, enslaved men and women were forced into a nine-story lazaretto, an Italian word meaning “pest house,” alongside rats and other vermin. They remained quarantined for days to protect Savannah’s population from infectious diseases. Slave traders and plantation owners eschewed any sort of dignified burial procession for those who died, burying them directly on Tybee Island.

Today, Black college students host their annual Orange Crush spring break celebration on Tybee Island. Savannah officials have taken efforts to limit the event’s success by increasing policing and denying permits, promoting narratives of the event as loud, dirty, and dangerous. On Tybee Island, the struggle for racial equality is far from over.

Listen to the author:

Learn more:

More photos from the Wade-in at Savannah Beach

Andrew Kahrl, The Land Was Ours: African American Beaches from Jim Crow to the Sunbelt South (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012)

William O’Brien, Landscapes of Exclusion: State Parks and Jim Crow in the American South (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2016)

Jeffery Finney and Amy Potter, “‘You’re out of your place’: Black Mobility on Tybee Island, Georgia from Civil Rights to Orange Crush,” Southeastern Geographer Volume 58, Number 1 (2018): 104-124