Photo by Raymond Boyd/Getty Images

Since 2017, Brazilian street artist Eduardo Kobra’s enormous nine-story mural of the bluesman known as Muddy Waters has towered over the corner of State and Washington across from the iconic Marshall Field & Co. building in the heart of the happening Chicago Loop.

It is a fittingly outsized and colorful tribute to one of more extraordinary and influential American lives, celebrating a sharecropper’s son from Mississippi who grew up without electricity but lived to inform the innovation of a vital music called rock ‘n’ roll.

McKinley Morganfield, known as “Muddy” since childhood, was born in the Mississippi Delta either in 1913 or 1915. In 1941, folklorist Alan Lomax, who entered the Delta to record its musical heritage for the Library of Congress, found him working sixteen acres and making his home in a cabin on the Stovall Plantation.

The purported remains of that dwelling are seen below as photographed around 1995, shortly before they were moved into the Delta Blues Museum in nearby Clarksdale.

Photo by Shepard Sherbell/Corbis Historical/Getty Images

Waters made a name for himself in those parts playing folksy blues numbers on Saturday nights at fish fries and juke joints. Lomax’s attention led him to think that he could be something special. So, in 1943 he took his sideline to Chicago–first playing at parties, then by invitation in clubs and taverns, earning sufficient notice that he was recruited in 1946 to join recording sessions for Columbia.

Waters made his debut record in 1947 with Aristocrat, an upstart Chicago label that Polish immigrant brothers Phil and Leonard Chess gained ownership of that same year and renamed after themselves in 1950. They subsequently released important tracks by the likes of Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley, and, on the recommendation of Waters himself, Chuck Berry.

By the early 1950s, when Waters sat in suit-and-tie with guitar for the promotional portrait featured below, he had established himself as a professional recording artist with multiple hits on Billboard magazine’s “Rhythm and Blues” chart, which had been titled “Race Records” until 1949.

Photo By Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Arguably the most important detail in the image of Waters above is the instrument. A scion of the agrarian south’s acoustic folk tradition gone to the industrial north, he began to play an electric by 1944. This was an entirely practical response to the challenge of playing audibly for the larger, livelier crowds he found in Chicago.

Electric guitars had been commercially available for just over a decade at the time and were still a relative novelty in popular music. This made Muddy Waters one of the earliest professional players to find success with one.

Waters made his transplanted Delta blues bolder by plugging in. Willie Dixon, his sometime bassist better remembered as a songwriter whose many important credits include the canonical Waters hit “Hoochie Coochie Man,” observed in retrospect that “Muddy was givin’ his blues a little pep” while so many of their contemporaries “was singin’ all sad blues” in the early postwar years.

The electric combos he formed to accompany him, which prefigured the prototypical rock lineup and sound, magnified this effect. The image below captures Waters in 1966 surrounded by a group much like those that had backed him for two decades at that point, including such distinguished regulars as Dixon on upright bass and Otis Spann on piano.

This photo was taken of an all-star blues showcase that aired on Canadian public television. Incredibly, it is among the earlier Waters performances of which footage exists.

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Waters’ vocal parts typically were boisterous to match his robust instrumental tracks and delivered with remarkable expression. The characteristic Waters persona was, not unlike his true self, a shameless, sometimes desperate womanizer prone to finding trouble.

Frankly provocative, the impression much of his music leaves is, as biographer Robert Gordon puts it, certainly “not the image of America that Eisenhower’s White House nor television’s ‘I Love Lucy’ suggested.”

The spirit expressed in his energetic blues, however immodest, was deeply authentic and proudly irrepressible. In this music, we can recognize a former sharecropper from Jim Crow’s Mississippi affirming his claim on life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness–on his terms.

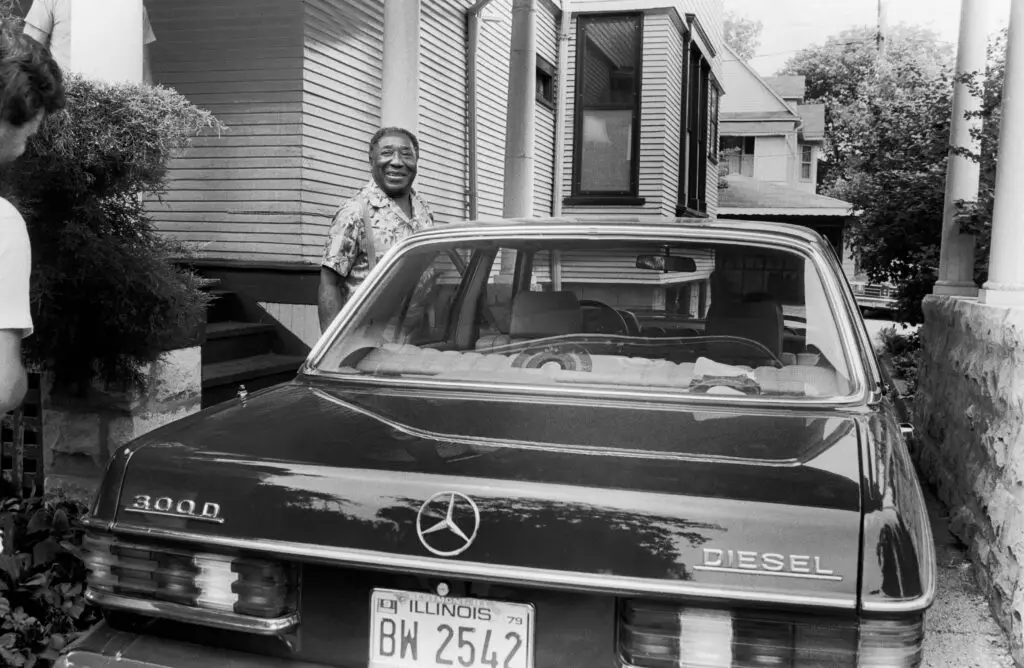

Muddy Waters died in 1983. It had been forty years since he made way to Chicago, and a decade since he moved out to an appreciable, but fairly unassuming suburban home in western Chicagoland. That residence provides the backdrop to the photo below of Waters posed with his Mercedes in the summer of 1981.

Dying at about seventy years of age, he was a younger old man when he went. Yet, while he was neither nearly the first nor the most popular of the early electric players, Waters lived to see himself become one of the very most influential to ever live.

Photo by Paul Natkin/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Despite declining health, those last ten years in the life of the gregarious man pictured here were some of his more fruitful.

He yielded an acclaimed comeback album under the supervision of an adoring Johnny Winter, was backed by The Band as he made a special appearance in their own celebrated concert film The Last Waltz, and played a valedictory of a club set on camera in 1981 with the Rolling Stones. They had taken their name from his 1949 single “Rollin’ Stone,” as at least partly did Bob Dylan’s pathbreaking single “Like a Rolling Stone” and the esteemed culture magazine Rolling Stone.

So immediately obvious as they are, these three namesakes ought to suffice as an enormous testament to the mark left on culture by a man whose lot for nearly half his life was the cotton fields.

Learn More:

Further Reading:

Can’t Be Satisfied: The Life and Times of Muddy Waters, by Robert Gordon (2002)

Muddy Waters: The Mojo Man, by Sandra B. Tooze (1997)

Out of the Blue: Life on the Road with Muddy Waters, by Brian Bisesi (2024)

Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta, by Robert Palmer (1982)

The Land Where the Blues Began, by Alan Lomax (1970)

Further Viewing:

Muddy Waters: Can’t Be Satisfied (2003, dir. Robert Gordon and Morgan Neville)

Muddy Waters: Got My Mojo Working – Rare Performances 1968-1978 (1999)

Chicago Blues (1792, dir. Harley Cokliss)

Sidemen: Long Road to Glory (2016, dir. Scott D. Rosenbaum)

The Last Waltz (1978, dir. Martin Scorsese)

Muddy Waters and the Rolling Stones: Live at the Checkerboard Lounge 1981 (2012)

Further Listening:

Muddy Waters, The Complete Plantation Recordings: The Historic 1941-42 Library of Congress Field Recordings (1993)

Muddy Waters, His Best, 1947-1955 – The Chess 50th Anniversary Collection (1997)

Muddy Waters, At Newport 1960 (1960)

Muddy Waters, Electric Mud (1968)

Muddy Waters, The London Muddy Waters Sessions (1972)

Muddy Waters, Hard Again (1977)