Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

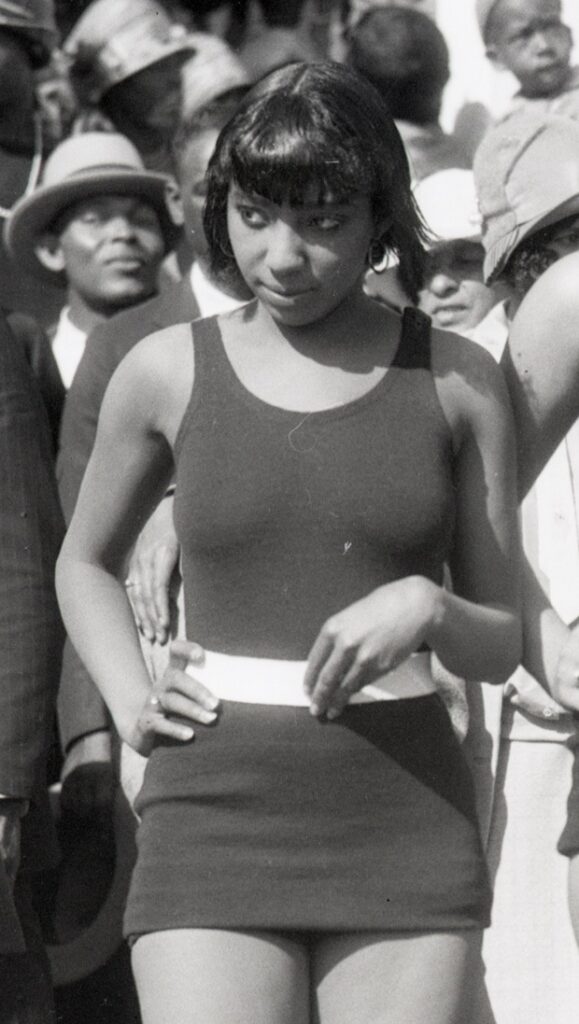

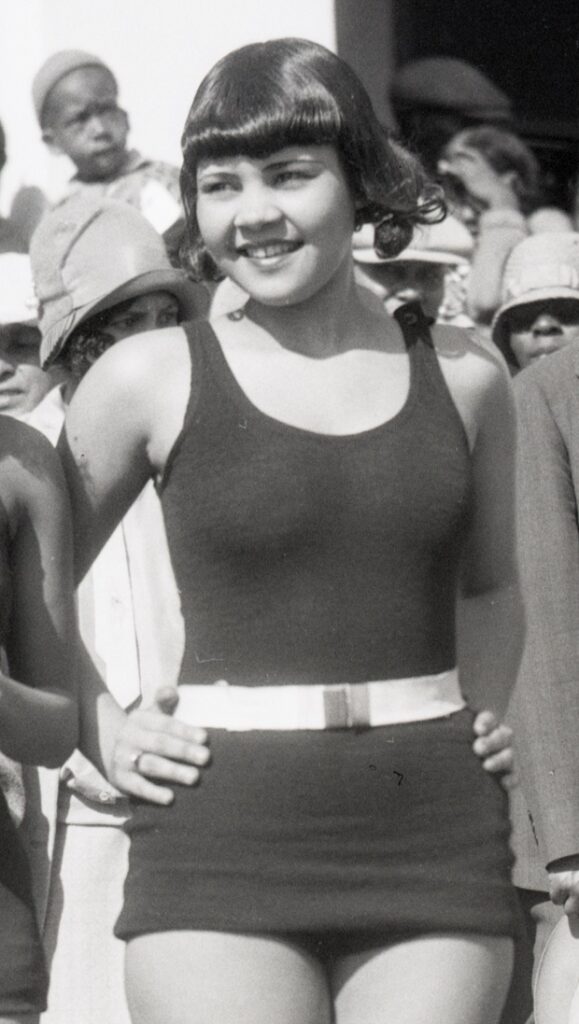

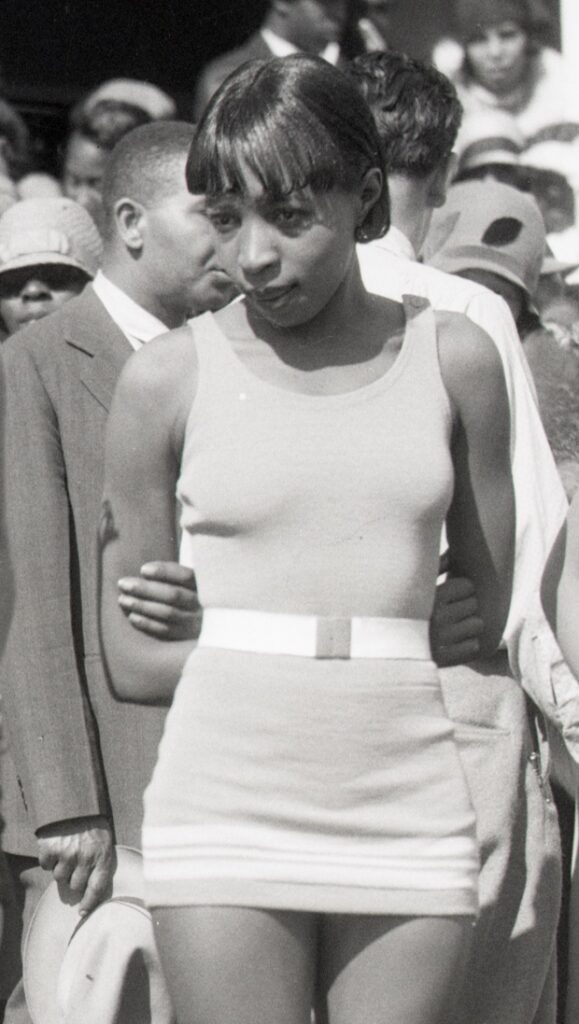

When the Parkridge Country Club opened in the summer of 1928, hundreds gathered to watch seventeen Black women compete in a beauty pageant for a prize of $2000, membership to the club, and the honorary title of “Miss Parkridge” (four contestants are pictured above). Located in Corona, California, Parkridge was the first country club to serve African Americans in greater Los Angeles.

Participating in a pageant was a rare opportunity for the city’s Black women during the 1920s. Women were often occupied raising children and working full-time as domestics, teachers, or nurses. The opportunity for young Black women to take center stage embodied one of many reasons why the African American community valued the Parkridge Country Club.

Southern California’s thriving economy attracted African Americans fleeing white supremacy in the South throughout the early twentieth century. However, migrants continued to face discrimination in all facets of life, including recreation.

Excluded from leisure spaces like Catalina Island or Griffith Park, they actively crafted their own recreational opportunities. Places like Bay Street Beach in Santa Monica, Lake Elsinore in Riverside, and Parkridge in Corona provided Black people sites of leisure, recreation, and the chance to build community away from the racial oppression clouding their everyday lives.

Parkridge’s opening-day beauty pageant was an example of the fragile promise of African American leisure spaces. While the contestants wore their bathing suits, the majority of those attending the beauty pageant arrived in formal dress, potentially suggesting an aspirational mindset toward Parkridge as a source of upward mobility.

The club’s founders—Dr. Eugene Nelson, Clarence Bailey, and Journee White—offered African Americans the opportunity to invest in Parkridge and to purchase estate sites on the club’s property. Thus, in addition to enjoying the club’s tennis courts, golf course, swimming pool, or gun range, its members could secure long-term investments and build generational wealth.

The importance of a country club for African Americans lay not only in its potential for leisure and wealth building, but also in the social capital it provided to its members. Aspiring business owners could make contacts that would build their clientele or lead to lucrative partnerships. For families the club was also a venue for matchmaking and romantic partnerships that could lead to marriage. As they gathered together to watch the beauty pageant, Parkridge’s members formed valuable connections.

While its target demographic was African Americans, Parkridge welcomed white patrons, as shown in the crowd. However, Corona’s white community did not take kindly to the country club. Upon learning that African Americans had purchased the club, white citizens lit a flaming cross on a hillside across from Parkridge. At the inaugural event, local policemen harassed club members with unwarranted traffic citations.

By 1929, white opposition coupled with financial troubles forced ownership to close the club.

When Mildred Boyd went home with the crown on that warm summer day in 1928, the promises of Parkridge were still fresh. Her career outlived the club, but it nonetheless mirrored the limitations of its promises.

Perhaps in part due to the exposure provided to her by the beauty pageant, Boyd pursued a successful career in Hollywood. She appeared in more than 200 films throughout the 1930s and 1940s. Like other Black actresses in those years, she most often portrayed a nurse or a maid.

Parkridge presented African Americans in greater Los Angeles with a rare space to relax and strengthen community ties. As the club’s swift closure showed, however, no space was free from the impacts of white supremacy and structural racism in the 1920s. African Americans’ struggle for leisure spaces persisted well into the twentieth century.

Learn more:

Alison Rose Jefferson, Living the California Dream: African American Leisure Sites During the Jim Crow Era (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2020)

Lawrence Culver, The Frontier of Leisure: Southern California and the Shaping of Modern America (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010)

Brian McCammack, Landscapes of Hope: Nature and the Great Migration in Chicago (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2017)