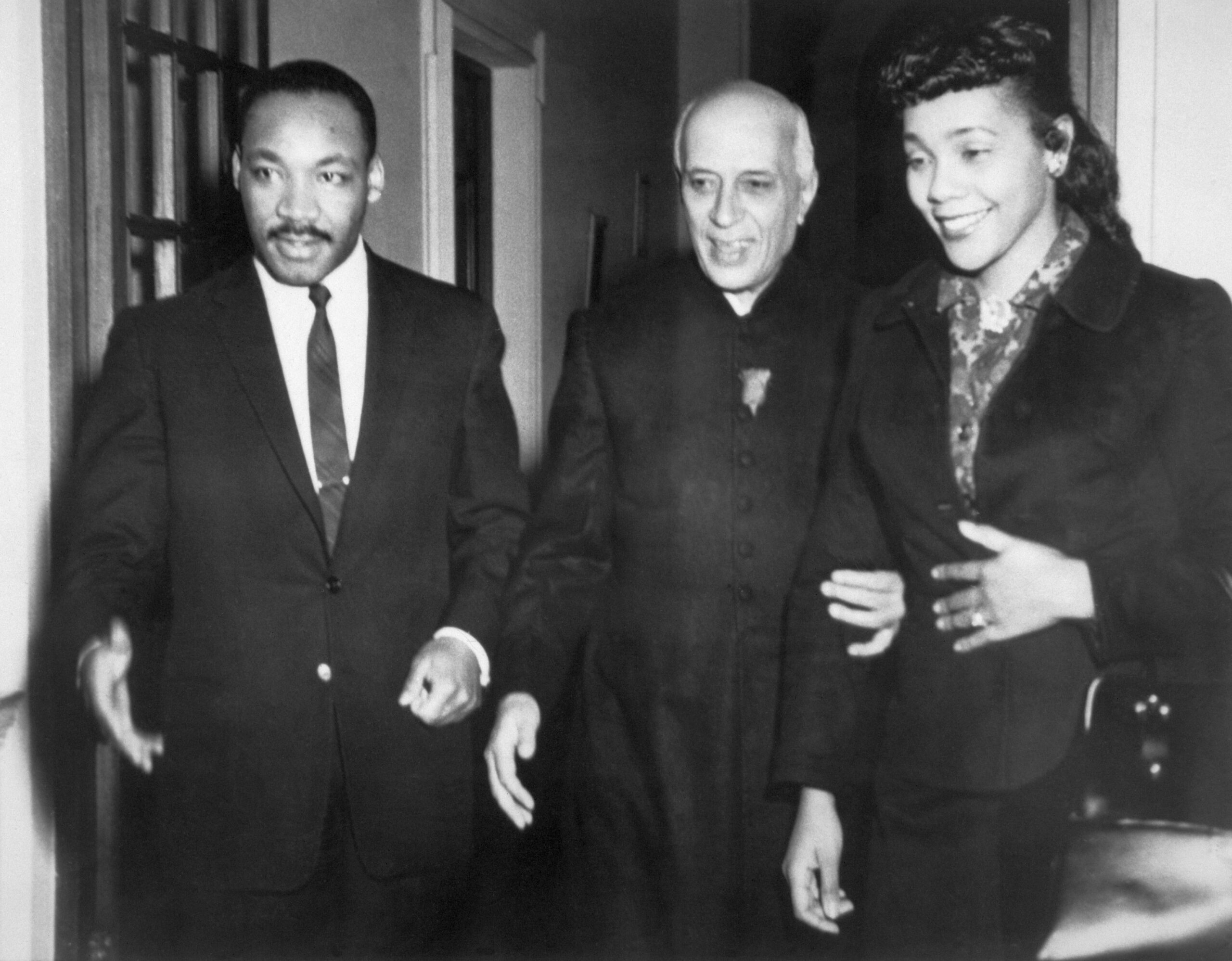

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

On February 18, 1959, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and his wife, Coretta Scott King, were greeted in Delhi by the Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru. A photo shows the three figures smiling, Nehru in the middle, a flower pinned to the hip-length fitted coat known to this day as a “Nehru jacket.”

In addition to speaking with Nehru, the Kings met with a range of prominent veterans of the Indian freedom struggle, including Jayaprakash Narayan, a socialist leader who had committed his life to anti-poverty work, and Rajendra Prasad, the President of India and a dedicated Gandhian pacifist.

Coretta Scott King remembered her husband comparing their schedule to “meeting George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison in a single day.” The trip was cosponsored by the Gandhi Smarak Nidhi (Gandhi Memorial Fund), and King was repeatedly heralded as the “American Gandhi.” As his conversations with Nehru reveal, however, his global vision extended well beyond Gandhian nonviolence.

From Delhi to Vietnam to the hills of Tennessee, King opposed the “three evils” of racism, materialism, and militarism and fought for a fundamental transformation of the United States and the world.

King and Nehru discussed the persistence of poverty in the United States and India, poverty that mapped onto inequities of race and caste. Asked about India’s granting of “reservations” in education and government employment to those who had suffered caste oppression, Nehru declared that such affirmative action policies were a necessary “way of atoning for the centuries of injustices we have inflicted upon these people.”

King recalled this conversation in one of his books, using the Indian example to argue for the necessity of confronting economic inequity in the United States. After returning home, he repeatedly linked the poverty he found in India to colonial rule, identifying lessons that he then applied to the necessity of combating inequality closer to home.

In an account of his trip to India that Ebony magazine published soon after he returned, King lamented the poverty and economic injustice he found in India and declared, “The bourgeoisie—white, black or brown—behaves about the same the world over.”

The economic dimensions of King’s global vision were on display again in October 1957, some six months after he returned from India, when he visited the Highlander Folk School, a tiny integrated institution in the hills of Tennessee. Founded as a labor school in 1932, Highlander had become an important nerve center for the growing civil rights struggle.

In his speech at Highlander, King praised labor unions as one of the Civil Rights Movement’s “strongest allies in the struggle for freedom,” and decried “the tragic inequalities of an economic system which takes necessities from the masses to give luxuries to the classes.” He also noted that Jim Crow segregation strengthened “communist appeals to Asian and African peoples.”

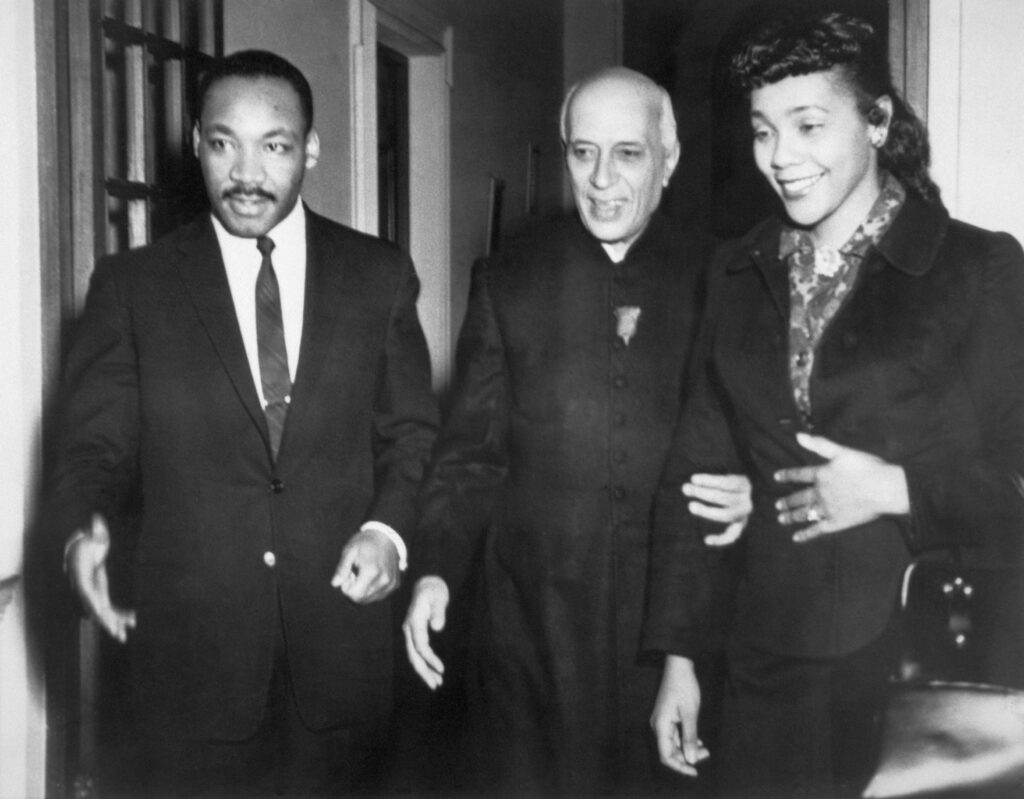

His suggestion that racism was providing fodder for communism did not prevent racists from attacking King as a communist. Indeed, the photo below, taken at that Highlander gathering, became the most renowned propaganda tool in the effort to attack King as a communist.

Photo By Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

In the photo, King is seated in the same row as Rosa Parks and Myles Horton, the founder of Highlander, but it was a relatively unknown figure, kneeling at the far left of the image, who provided fodder for those who wished to link King to communism.

Abner Berry, an African American communist who wrote for The Daily Worker, had not identified himself to King or any of the Highlander staff. Neither had the photographer, Edwin H. Friend, who was spying for the state of Georgia.

The image Friend captured was first distributed in a four-page broadside produced by the Georgia Education Commission (GEC), a pro-segregation publicity group that aimed to attack Highlander, King, and the Civil Rights Movement as a whole. The GEC printed over 200,000 copies, and the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist organizations helped to distribute them.

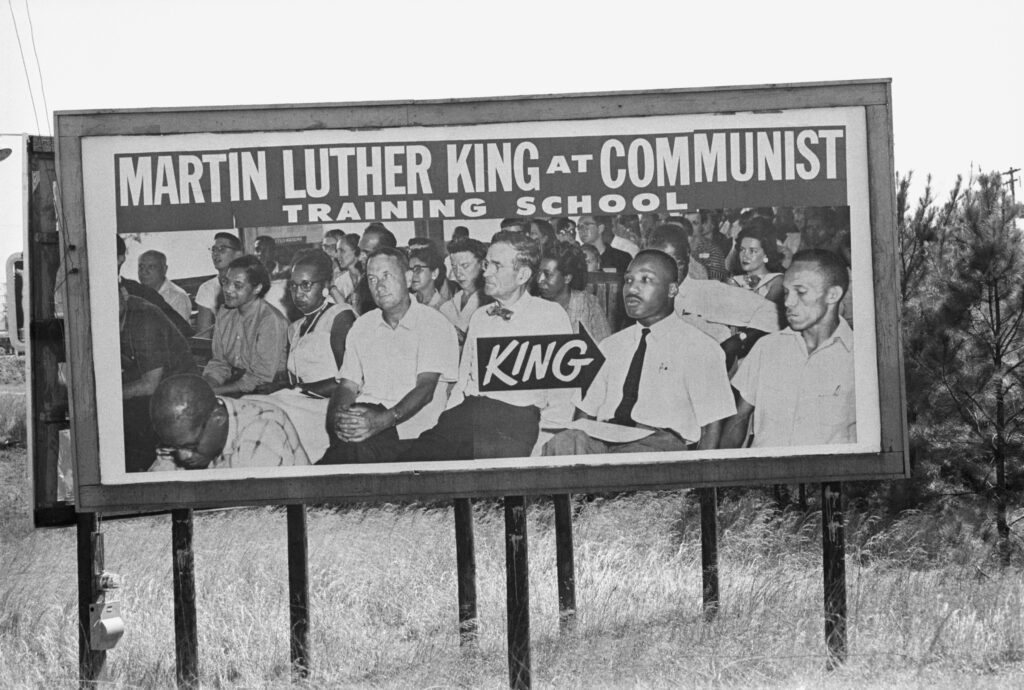

In Spring 1965, the image gained even more notoriety when it was pasted on hundreds of billboards across the American South as proof that King had attended a “Communist Training School.” He was not a communist, but he was a critic of capitalist inequity who had long recognized the ties among inequity, racism, and other forms of injustice—including imperialism and militarism.

In March 1965, at the same time that the “Communist Training School” billboards went up across the South, King spoke out publicly for the first time in opposition to the war in Vietnam. He lamented that “millions of dollars can be spent every day to hold troops in South Viet Nam and our country cannot protect the rights of Negroes in Selma.”

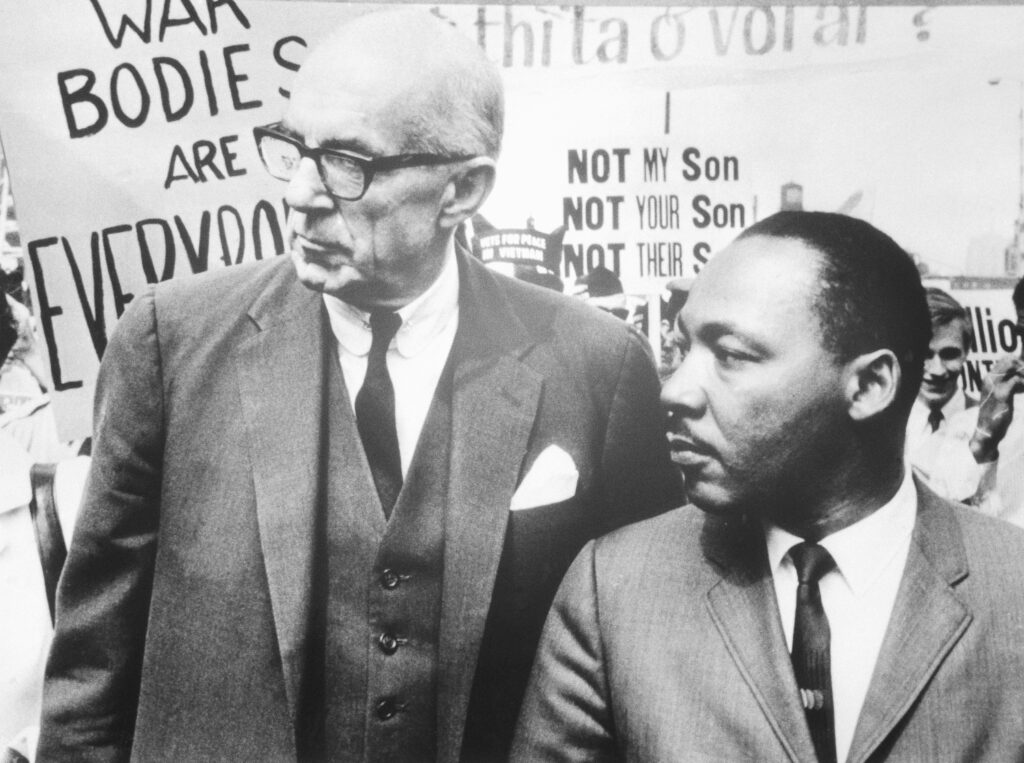

On January 25, 1967, he was photographed alongside the prominent pediatrician and antiwar activist Dr. Benjamin Spock while helping to lead an antiwar march in Chicago.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

Three months later, in April 1967, King took to the pulpit at Riverside Church in New York to offer his most renowned statement in opposition to the war in Vietnam. As the photo of him and Dr. Spock demonstrates, he had already formed public alliances in opposition to the war. King opposed the war in Vietnam as an advocate of peace and nonviolence, but also as a fierce critic of imperialism and of the maldistribution of resources.

Linking this photo to the snapshot of King at Highlander and the image of the Kings with Nehru in Delhi uncovers the interconnected nature of King’s global vision, as well as the radical depth and breadth of that vision.

Learn More:

Tommie Shelby and Brandon M. Terry, eds., To Shape a New World: Essays on the Political Philosophy of Martin Luther King, Jr. (Harvard University Press, 2020)

Vicki L. Crawford and Lewis V. Baldwin, eds., Reclaiming the Great World House: The Global Vision of Martin Luther King Jr. (University of Georgia Press, 2019)

Nico Slate, Colored Cosmopolitanism: The Shared Struggle for Freedom in the United States and India (Harvard University Press, 2012)