Photo by Keystone/Staff/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

All the world over, Black people have fought their oppression in inventive ways.

Music continues to provide an avenue for Black people to voice their resentments, nurture hope in an otherwise grim world, foster collaborations among musicians, and establish transcontinental connections between Africa and its diasporas. It is a medium with a long underrecognized tradition of lyrical engagements and interactions among Black musicians on and off the African continent, all aiming to sing justice into existence for all Black people.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

Wennyuk’uMbombela [There goes the train]

– “Train Song” from An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba

Wenyuk’ekuseni [it goes in the morning]

Weh bab’uyandishiya [oh father it is leaving me behind]

Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba were among the most notable artists engaged in this intercontinental collaboration among Africa, the Caribbean, and North America. Pictured above in 1966 with their Grammy Award for the Best Folk Song on the album An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba, the two were inseparable in their lyrical quest to capture Black joy.

With Belafonte facing segregation in the U.S. and Makeba in exile from apartheid South Africa, both fought oppression most of their lives. They seamlessly recognized each other’s distinct encounters with Black struggle, which strengthened their musical collaborations and underlay their acknowledgement of the universality of Black people’s plight. In 1963, the two had travelled to the motherland to share in the glory of Kenya’s independence from British colonial rule.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

All I want is equality

– “Mississippi Goddam” from Nina Simone in Concert

for my sister, my brother, my people, and me

On March 18, 2022, the reggae artist Stephen Marley produced Celebrating Nina: A Reggae Tribute to Nina Simone in honor of the legendary singer and songwriter. The EP brought together a young generation of female reggae artists from Jamaica, all of whom were influenced, one way or another, in their musical careers by Simone’s melodic prowess. It memorialized her art in the rhythms and upbeat tempos of reggae, an indication of the wide reach of her music in the Black world.

Like Stephen’s father, the legendary reggae artist Bob Marley, –Simone was profoundly aware of the interconnectedness of Black struggles. In her music, she mapped out the intercontinental reach of racial prejudice she encountered as a Black woman.

A visit to Nigeria in 1961 lent a fiery perspective to her position on the universal nature of Black oppression and shaped her musical career. Her Pharaoh-styled scarf in this photograph is one of the ways she gestured to the continent for both lyrical and artistic inspiration.

Photo by Mike Moore/Daily Express/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

nijo wo la ma bo ooo [when will we be free]

– “Black Man’s Cry” from Live!

l’oko eru [from the slave plantation]

Almost a decade after Simone visited Nigeria, Fela Kuti journeyed from Nigeria to the U.S. in 1969. The Africanist Tejumola Olaniyan, in his cultural biography of Fela, described his 10-month stay in the U.S. as the catalyst for Fela’s “transformation into a socially conscious exponent of afrobeat,” a more radical musical genre.

He and his band performed at an NAACP event in Los Angeles, where he met the Black Panther member and activist Sandra Smith Izsadore, who eventually became his mentor. Speaking about his encounter with her, Fela noted: “Sandra gave me the education I wanted to know. She is the one who spoke to me about… Africa. For the first time I heard things I had never heard about Africa.”

Upon his return to Nigeria, Fela produced songs that highlighted the interconnected plight of Black people all over the world. He lived the remainder of his life rendering his sentiments about corruption in his country and imperialism in Africa on his signature wind instruments. The soprano saxophone pictured here was one of many instruments that accompanied his unapologetic protest songs.

Photo by Keystone/Staff/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Every man got the right to determine his own destiny

– “Zimbabwe” from Survival

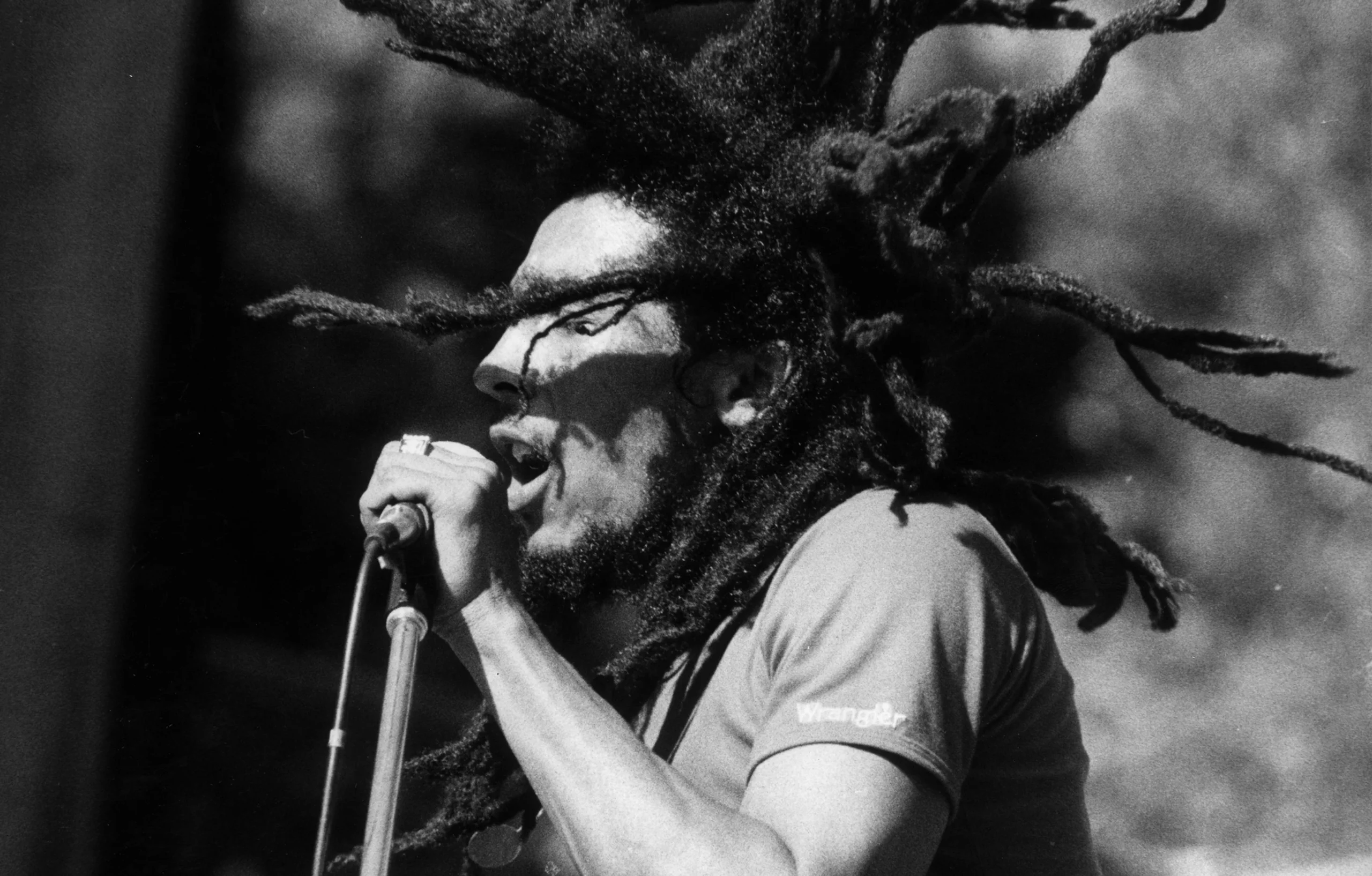

Like Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba, Bob Marley and the Wailers graced the continent with their performance at Zimbabwe’s independence day celebration on April 18, 1980. On that day, the renowned reggae artist skanked to the lyrics of the song “Zimbabwe,” which he had composed in Ethiopia.

This photograph of him in motion captures the zest with which he and other reggae artists approached reggae music as a fervent message about hope to the oppressed. This message continues to reverberate in all corners of the world where Black people have been subjected to oppression.

That Bob Marley wrote “Zimbabwe” in Ethiopia was fitting. For many Rastas, Ethiopia was the point of reference when Marcus Garvey prophesied the ascent of Haile Selassie I to the throne and his role as the Black messiah. Seen differently, the gesture captures the spirit of oneness of the Black race. It was a “Redemption Song” by an Afro-Caribbean reggae band in honor of an African nation’s sovereignty after almost a century of British colonization.

These four musicians and songwriters reached the peak of their musical careers sometime between the 1940s and the early 2000s, with Bob Marley and Fela Kuti’s music truncated by their untimely deaths.

The depth of their impact on the Black music scene and activism cannot be measured solely on their accomplishments during this period, because generations of Black artists continue to draw inspiration from them. Lauryn Hill, Somi, Beyoncé, Nas, Damian Marley, Kendrick Lamar, and Burna Boy, among many others, have imbibed the style of these musicians and songwriters. They continue to channel the message of Black liberation into their lyrical and visual content on account of this influence.

Together, these old and new musicians form a continuum of Black intercontinental and intergenerational lyrical connections sustained by each new generation’s consciousness of the struggles of the Black race.

Listen to the author:

Learn more:

Barrett, Leonard E. The Rastafarians: Sounds of Cultural Dissonance. Boston: Beacon Press, 1997.

Belafonte, Harry and Michael Shnayerson. My Song: A Memoir. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2011.

Dawes, Kwame. Bob Marley: Lyrical Genius. London: Sanctuary Publishing Limited, 2002.

Feldstein, Ruth. ““I Don’t Trust You Anymore”: Nina Simone, Culture, and Black Activism in the 1960s.” Journal of American History, Vol. 91, No. 4 (2005), 1349-1379.

Makeba, Miriam and James Hall. Makeba: My Story. New York: New American Library, 1987.

Olaniyan, Tejumola. Arrest the Music!: Fela and His Rebel Art and Politics. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2004.