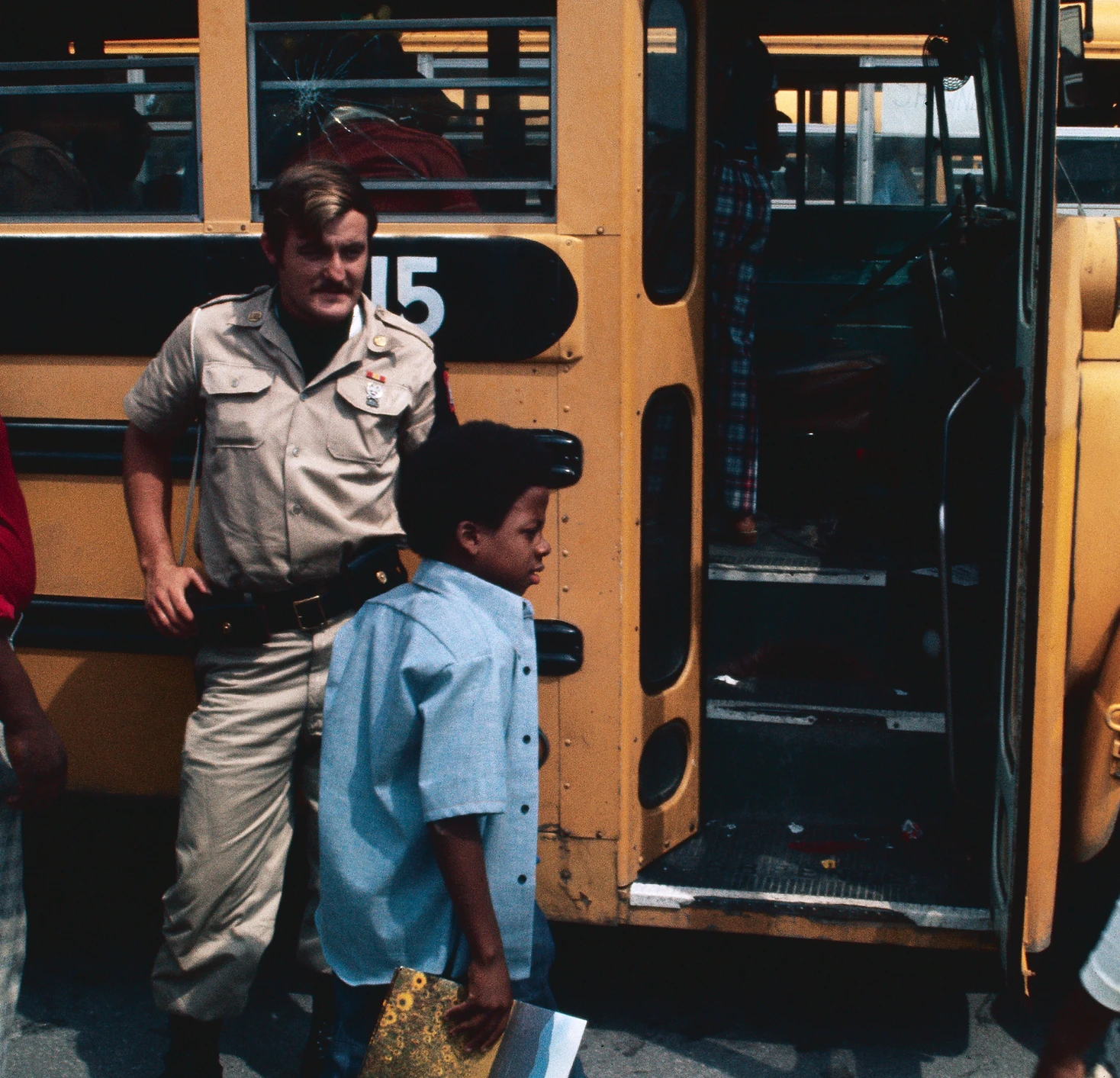

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

The integration of Louisville’s public schools began smoothly enough, all things considered. Attendance was half what it ought to have been on the first day of classes, thanks to a white parents’ boycott and a great deal of fear. Eight of the district’s 165 schools were evacuated because of bomb threats. And the police arrested a white kid for throwing stones at the Black kids at Fairdale High on the district’s seething south side.

But there weren’t any large-scale incidents around the buses or out in the streets, as many people had feared there might be. In September 1975 that counted as a victory.

It had been 21 years since the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had convinced the Supreme Court to declare the legislated segregation of public schools unconstitutional. Prohibiting segregation was one thing, though; integration was decidedly another.

For more than a decade after the Court’s decision, districts could bring themselves into compliance by allowing a single Black child, like little Ruby Bridges, into their otherwise completely white schools. Only in May 1968 did the justices decide—in another NAACP case—that it was time to bar legally segregated systems altogether and to put in their place genuine integration.

What followed was arguably the most radical turn of the civil rights revolution. Across the country NAACP lawyers and their legal allies filed suit to force districts to comply with the Court’s new ruling. The only way to do that, they argued, was to move a substantial portion of white children into Black schools and Black children into white schools, until their color lines were obliterated.

In the largest districts the numbers were startling: to integrate the Los Angeles school system, the NAACP proposed busing 250,000 kids a day, white kids in one direction, Black kids in another. The protests that brought down Jim Crow in the mid-1960s had been more dramatic, the recent demonstrations of Black Power more startling to white America. But never before had the civil rights movement tried to place the weight of racial change so directly onto millions of white families.

White Americans responded with countersuits, petition drives, recall campaigns, and protest marches meant to mimic the ones the civil rights movement had staged in its glory days.

When those tactics failed and the buses started to run in district after district, a striking share of white people turned to massive resistance, part of the larger efforts of segregationists to resist federal integration law. Busing defiance began in the Deep South in 1970-71, then followed the courts’ rulings north to its furious peak in blue-collar Boston in 1974-75, busing’s most brutal school year yet with widespread rioting and violence.

Louisville’s turn came on Friday, September 5, 1975, the second day of the academic year. There were flashes of violence in the morning as the buses pulled into the south side high schools; worse when classes let out that afternoon and knots of white people took to pelting the buses with rocks and bottles.

From there the crowds swelled—drawn in by Friday football—until by nightfall 1,000 people had gathered around Southern High and maybe ten times that number at Valley High, out on the southwest side’s Dixie Highway. The rioting started shortly thereafter in a paroxysm of white rage: mobs on the highway stoning cars; mobs on the business strips smashing store windows; mobs in the school parking lots burning buses; mobs brawling with the police.

The next morning the governor ordered in the National Guard. The mayor put in place a ban on anti-busing protests. And the local authorities announced that come Monday each of the district’s buses would have a policeman aboard.

This photo was taken a few days later, as the Black students at one of the south side schools boarded the buses that would take them home. By then the crowds around the high schools had been cleared away. The bomb threats had stopped. Even the boycott was fading, eighty percent of white parents having decided that they’d send their kids to school after all.

And the heaviest burden of integration had been pushed back onto the thousands of Black children whose route to and from school now came with an armed escort for fear of what white people might do.

Listen to the author: