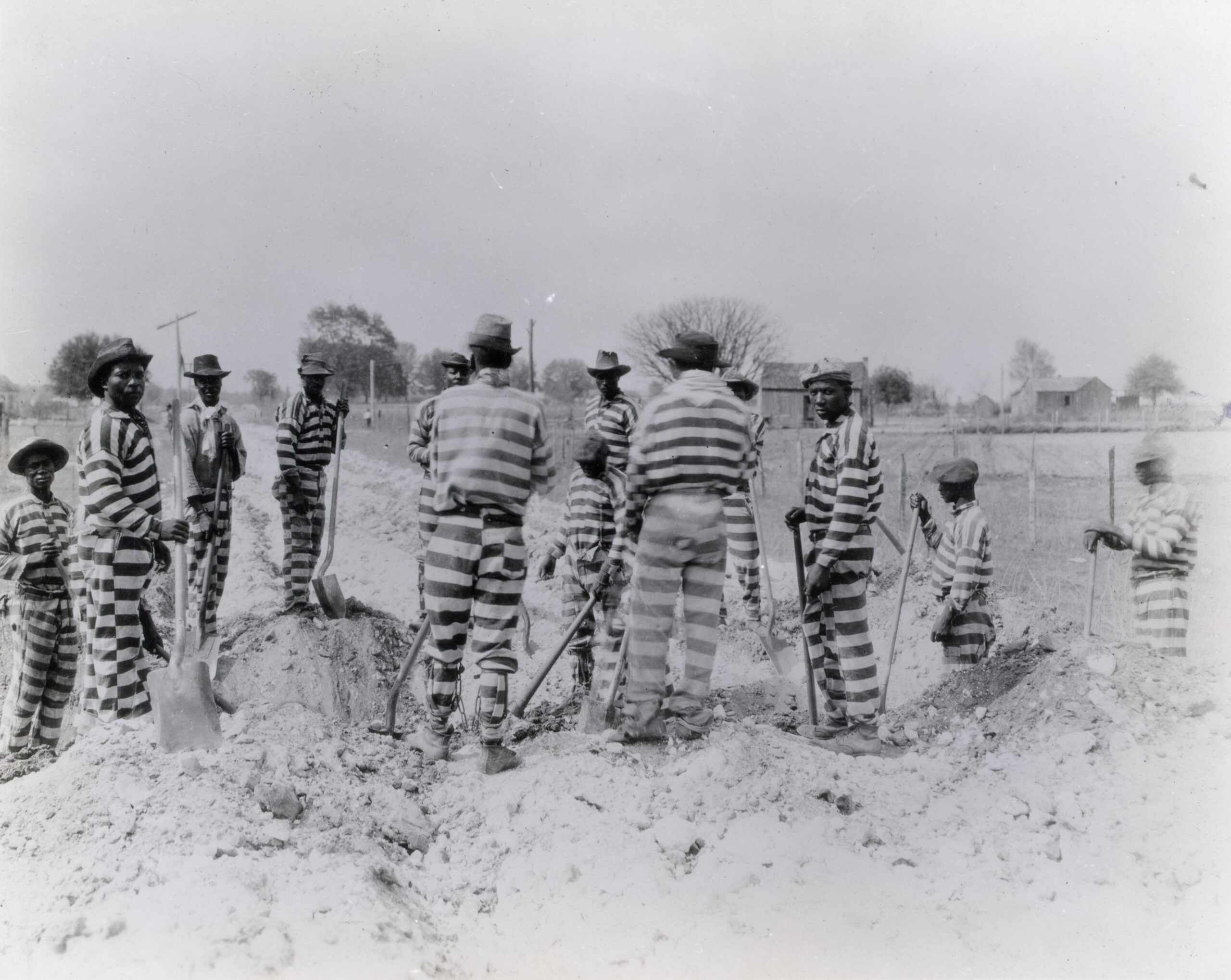

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Dressed in black-and-white striped uniforms and holding shovels, the unnamed incarcerated Black men in the above picture (ca. 1900) paused their arduous work on a road in Florida to stare piercingly into the camera. Their uniforms highlighted their status as prisoners, but the shackles attached to the ankles and thighs of the man in the center with his back turned to the photographer communicates this status even more viscerally.

Though slavery supposedly had ended in 1865, freedom likely seemed far away for the men photographed here.

Although the Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution had abolished the institution of slavery in 1865, the amendment made an exception: Slavery was banned “except as a punishment for crime.”

Following the end of the Civil War, local and state officials, private companies, and white Southerners took advantage of this clause as they established and participated in a system called convict leasing. Simultaneously, Southern criminal legal systems convicted Black Southerners at high rates after the Civil War, allowing the convict lease system to rely on Black labor.

Adopted by several Southern states in the years after emancipation, the convict lease system granted county and state governments the authority to rent out incarcerated people to private individuals and companies. Some states, including Texas and Louisiana, even leased entire populations of state penitentiaries to lessees. Lessees became responsible for feeding, clothing, guarding, and punishing the incarcerated people under their control.

While a few states, such as Louisiana and Alabama, had engaged in convict leasing before the Civil War, 12 postbellum Southern legislatures embraced the system in order to defray the costs of the growing incarcerated populations, reduce the overcrowding of jails and prisons, increase profits, and control the freedom and labor of formerly enslaved people.

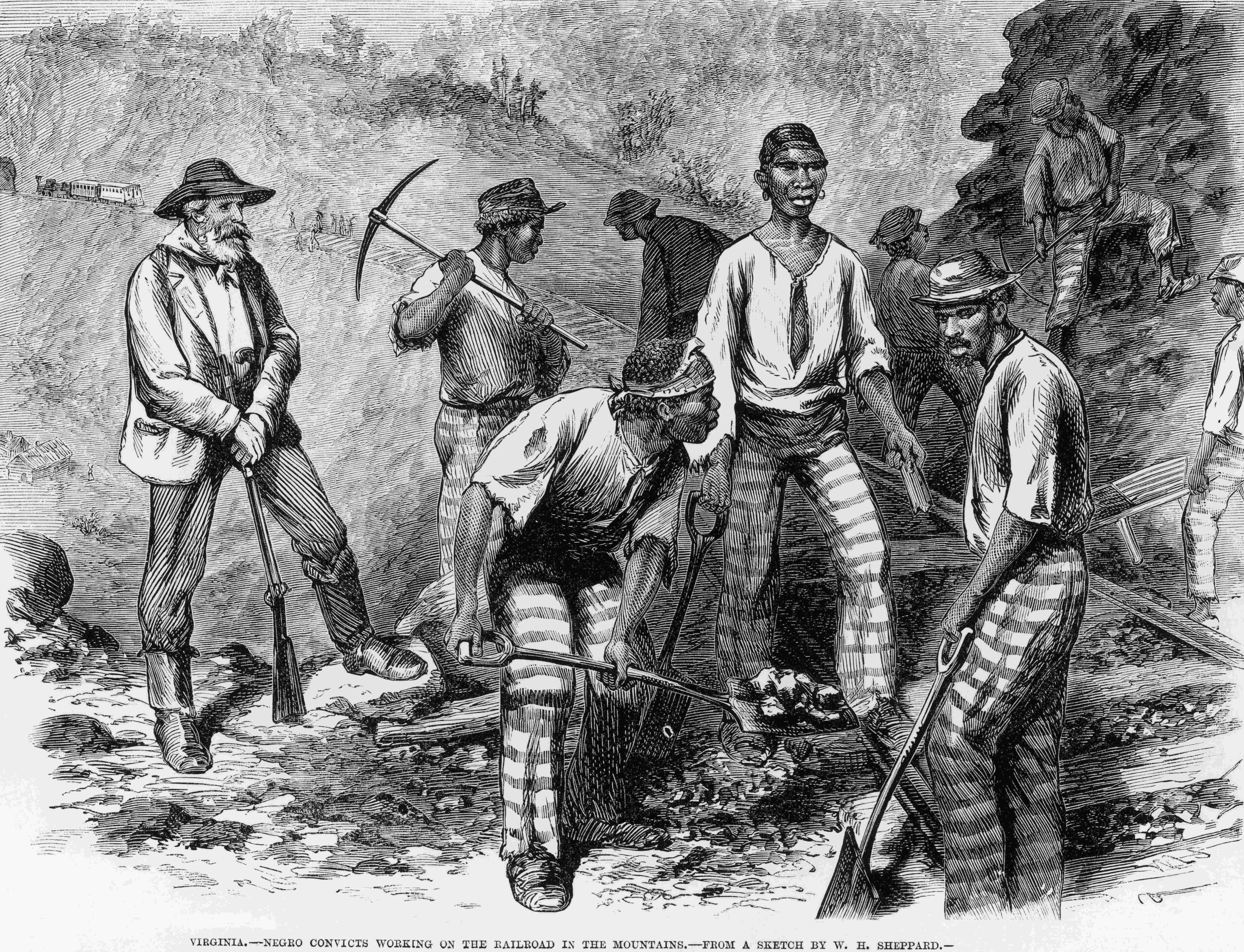

Photo by Photo by Fotosearch/Getty Images

Railroad companies became one of the earliest and most prominent industries to rely on leased convict labor after emancipation. The W.H. Sheppard engraving above (ca. 1870) demonstrates this trend. Under the watchful eye of a white guard who holds a rifle, the incarcerated Black men perform the demanding work of laying mountainside railroad tracks in early 1870s Virginia.

Although the engraving portrays Virginia, incarcerated people’s labor on railroads across the entire South were essential contributions to industrialization after the Civil War.

Lessees’ use of incarcerated men, women, and children extended to a number of other industries as the nineteenth century continued. In addition to railroads, incarcerated people labored on plantations and in mines, quarries, lumber yards, iron works, and factories. Convict labor became a massive source of revenue for lessees and the state.

The drive to increase profit and lessees’ belief in the disposability of Black prisoners predictably produced deadly conditions for those forced to serve part or all of their sentences under the convict lease system. This included poor living conditions, backbreaking labor, and violence.

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

The photograph above (ca. 1900) offers a brief glimpse of this violence. A white man, likely a dog sergeant, trains three hounds to attack an incarcerated Black man. In the same way that enslavers and slave patrollers used hounds to hunt down runaway enslaved people, prison guards utilized bloodhounds to track and viciously attack incarcerated people who attempted to escape.

Lessees and prison officials relied on routine violence to control and terrorize their incarcerated labor forces, such as hounds, whippings, sexual violence, and other physical punishments.

However, incarcerated Black people adopted several strategies to navigate and resist the violence they experienced, including escaping, writing letters to state officials, stealing from lessees, organizing mutinies, and many other methods.

Between the 1890s and the early twentieth century, an anti-convict leasing movement emerged as public outrage about the system grew throughout the United States. Opponents argued that the convict lease system undermined free laborers and created inhumane conditions for incarcerated people.

Black activists, such as Ida B. Wells-Barnett, objected to convict leasing for the insidious role it played in limiting the rights of Black Southerners. In her 1893 pamphlet The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition, Wells poignantly argued that high conviction rates for Black men “not only means able-bodied men … swell the state’s numbers of slaves, but every Negro so convicted is thereby disfranchised.” According to Wells, the convict lease system served as an important tool of white supremacist lawmakers and citizens who sought to remove Black people’s freedom and citizenship rights.

Ultimately, through the work of Black activists like Wells and other prison reformers and labor movement activists, several Southern states began passing laws to end convict leasing at the state level between the 1890s and early twentieth century. The Tennessee General Assembly abolished leasing in 1896, for example, whereas Alabama did not end the practice until 1928.

However, the abolition of the lease system did not result in the end of convict labor. Instead of leasing incarcerated people to individuals and companies, the state still required labor from incarcerated people but assumed responsibility for their care and reaped the profit for themselves.

Many Southern states constructed state-owned prison plantations, such as Parchman Farm in Mississippi and Imperial State Farm in Texas. Most former convict leasing states organized incarcerated people into chain gangs, directly profiting off the labor of predominantly Black incarcerated populations.

Despite the abolition of slavery in 1865, the forced labor of incarcerated people has been a longstanding challenge to the freedom Black people have secured, even to this day.

Learn More:

Haley, Sarah. No Mercy Here: Gender, Punishment, and the Making of Jim Crow Modernity. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2016.

LeFlouria, Talitha. Chained in Silence: Black Women and Convict Labor in the New South. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2015.

Lichtenstein, Alex. Twice the Work of Free Labor: The Political Economy of Convict Labor in the New South. New York: Verso Books, 1996.

Mancini, Matthew J. One Dies, Get Another: Convict Leasing in the American South, 1866-1928. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1996.

Wells, Ida. B. The Reason Why the Colored is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition: The Afro-American’s Contribution to Columbian Literature. Chicago: Ida B. Wells, 1893.