Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Nicholas Hood, pastor of the Plymouth Congregational Church in Detroit, looked around and asked himself: Where did all these people come from? This question captured his breathless amazement at the size of the crowd, but, in fact, it had an easy, straightforward answer: Detroit.

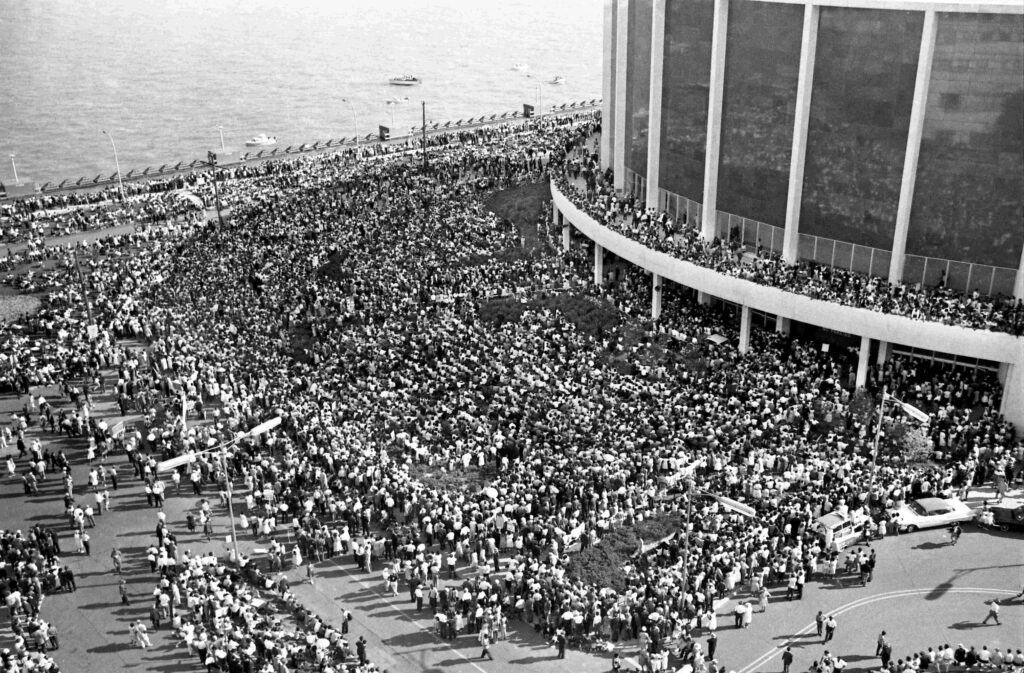

It was June 23, 1963. Hood was standing on Woodward Avenue, one among an estimated 125,000 who had come that day to participate in the “Walk to Freedom.” Two months almost to the day before civil rights marchers gathered on the National Mall, they walked down Woodward Avenue all the way to Cobo Hall in what was the largest civil rights demonstration to date in the country’s history.

Woodward Avenue, the major north-south route through the heart of Detroit, was a boundary, separating Detroit’s east side from its west. It was a bustling meeting place filled with stores, churches, jazz clubs, and theaters—a microcosm of Detroit’s energy in one place.

The Walk had come together quickly, in just six weeks, and was organized by a loose and fractious coalition of church leaders and civil rights activists calling itself the Council for Human Rights chaired by the flamboyant Rev. C. L. Franklin, pastor of New Bethel, one of the largest Black churches in the city, and father of the singer Aretha.

The Detroit chapter of the NAACP stayed away from the organizing, but once it became clear just how big the event would be, they rushed to print posters for marchers to carry.

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

It helped that the city’s establishment, rather than opposing the Walk or tangling it up in bureaucratic red tape, endorsed the event. Mayor Jerome Cavanaugh spoke on the dais to give an official welcome to the crowd at Cobo Hall. Police Commissioner George Edwards insisted to his force: “I want this event to be peaceful and happy.”

Michigan governor George Romney issued a proclamation that June 23, 1963 would be “Freedom March Day.” And powerful Walter Reuther, who ran the United Auto Workers from Solidarity House on East Jefferson Avenue, was deeply committed to racial equality. He spoke too.

The Walk also offered Detroiters the chance to exorcise some demons. Twenty years earlier, almost to the day, Detroit had erupted in racial violence, most of which took place in the Black Paradise Valley section of the city. By the time it was over, 34 people lay dead, 25 of them Black.

Nor was the irony lost on marchers that they finished their walk at Cobo Hall. The city’s new convention center had opened in 1960 and was named for former mayor Albert Cobo. Cobo had built his political career on unapologetic race-baiting and implacable opposition to open housing. Now tens of thousands of Detroiters marched to Cobo Hall in the name of civil rights.

Big as it was, Cobo Hall could not accommodate the crowds. As the photograph below shows, thousands stood outside in the warm June afternoon trying to listen to the speakers on a sound system. Many stayed even though they couldn’t hear a word.

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

So many people gathered at the staging ground that the Walk actually kicked off an hour before it was scheduled. The early start meant that, when he arrived from the airport, the guest of honor had to scramble to get to the front of the march. Martin Luther King, Jr., in the midst of his campaign in Birmingham, flew into Detroit, and was greeted by Commissioner Edwards.

When he finally spoke at Cobo Hall, King called the Walk the largest and greatest demonstration for freedom in American history and he marveled at the peacefulness of it all—not a single episode of violence, according to Commissioner Edwards.

With preliminaries out of the way, King went on to deliver a stirring speech.

As it crescendoed, he told the crowd about a dream: “And so this afternoon,” he began, “I have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream. . .” And he finished: “we will be able to achieve this new day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing with the Negroes in the spiritual of old: Free at last! Free at last! Thank God almighty, we are free at last!”

The press didn’t much notice this part of King’s speech. The New York Times didn’t mention it at all in its coverage and King would tweak it before he delivered it again on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

What became arguably the greatest political speech of the 20th century got its dress rehearsal in Detroit. And for a day in 1963 Detroit shined as the opposite of Birmingham, a mirror image to show the nation what racial progress could look like.

Learn More:

Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis, (Princeton: 1996)

Thomas Sugrue, Sweet Land of Liberty: The Forgotten Struggle for Civil Rights in the North, (Penguin: 2008)

David Maraniss, Once in a Great City: A Detroit Story, (Simon & Schuster, 2015)

Gerald Early, One Nation Under a Groove, (Echo Press, 1995)

Heather Ann Thompson. Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City, (Cornell University Press, 2017)

Grace Lee Boggs. Living for Change: An Autobiography, (University of Minnesota Press, 2016)