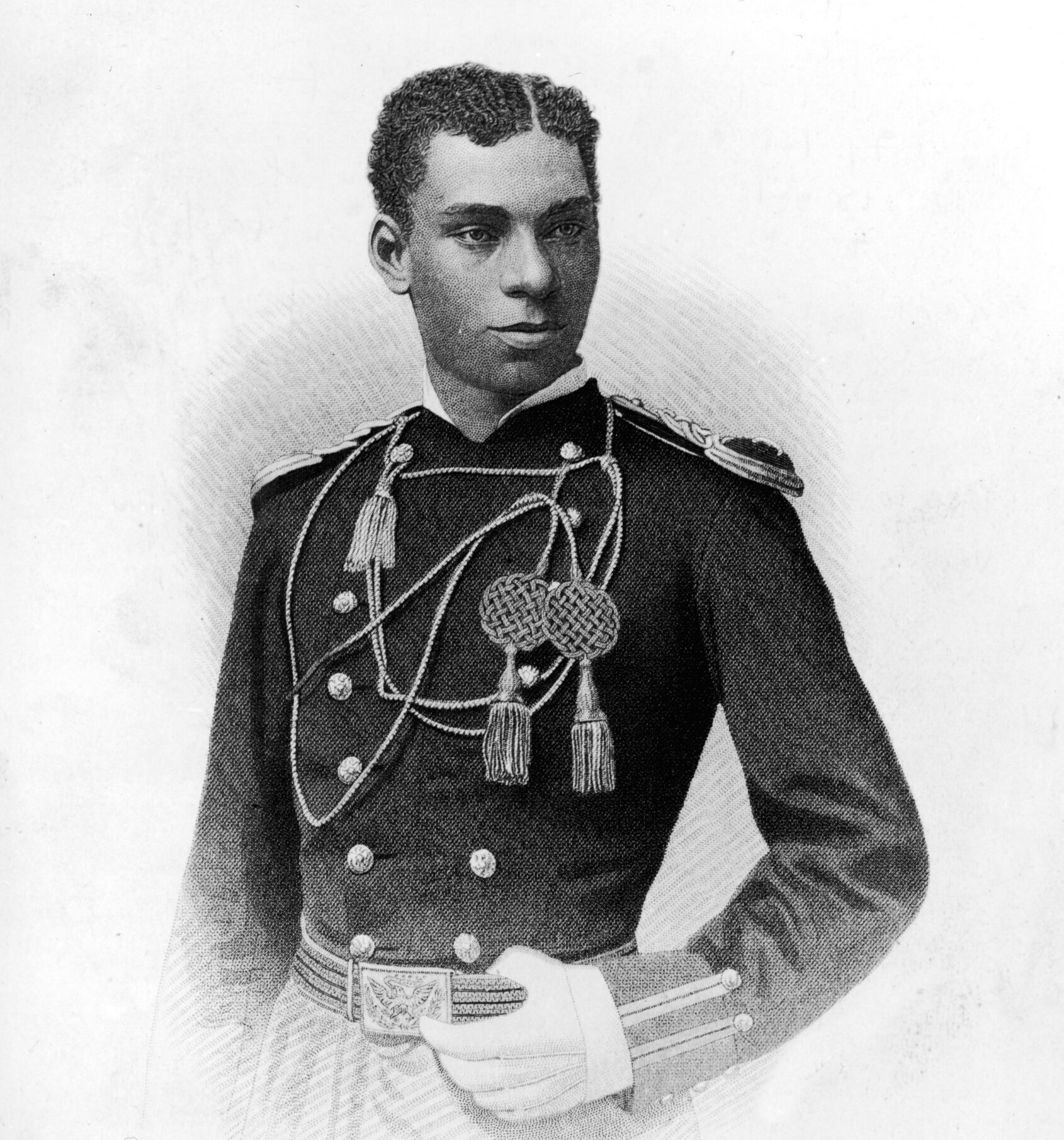

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The story of Henry Ossian Flipper, the first Black American to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point, remains a tale largely unknown. Far from a simple success story, Flipper’s life reads like the biography of an antihero: celebrated one moment, ostracized the next; lauded for his talents yet denounced for his convictions.

His journey—from enslavement in Georgia to West Point, from pioneering engineer to dishonored officer and finally to respected civilian expert—reveals a complex man whose fierce independence both elevated him and isolated him from the communities he once represented.

Born into slavery in Thomasville, Georgia on March 21, 1856, Flipper grew up on the Ponder plantation. Two men shaped Flipper: John F. Quarrels and James Webster Smith.

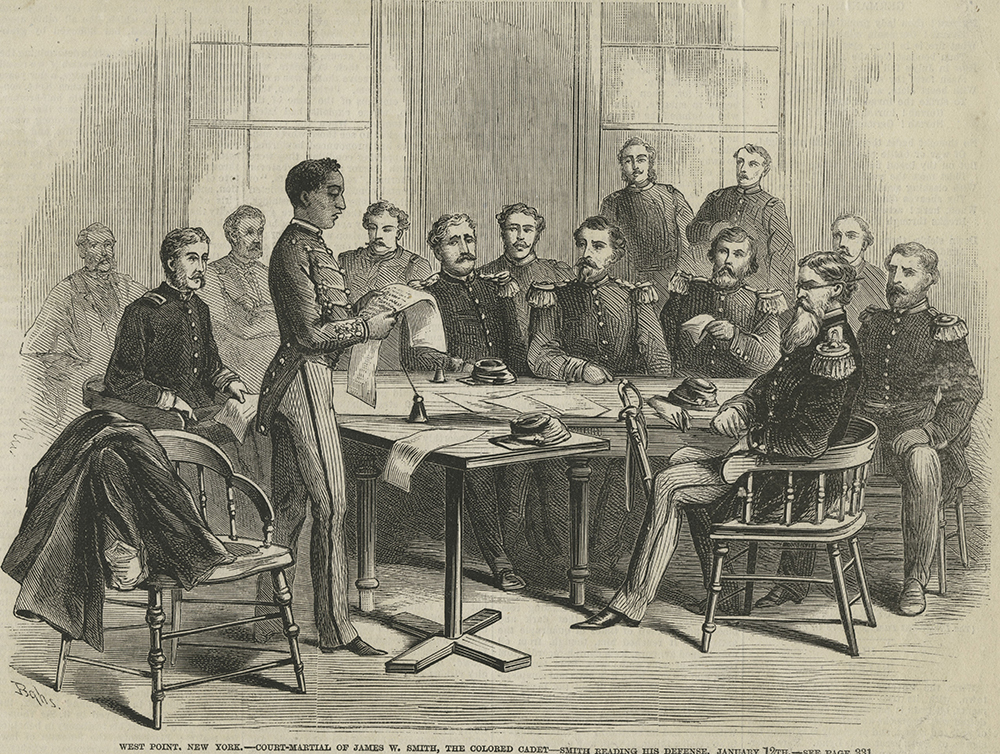

Quarrels, the first Black member of the Georgia Bar, served as young Henry’s teacher and role model. He inspired Flipper to master Spanish. Smith was already famous as the first Black American admitted to West Point in 1870, though his time there proved tumultuous.

Yet it was witnessing Sherman’s March to the Sea that awakened in him an unexpected sympathy for the dying Confederate soldiers and sparked his ambition to wear the U.S. Army’s uniform.

Flipper arrived at West Point in 1873, well aware of Smith’s bitter struggles there. Smith had faced relentless harassment, three court-martials, and eventual dismissal just a year before graduation (the drawing below captures Smith reading his defense statement at his court-martial hearing at the United States Military Academy, January 12, 1871).

Smith even roomed with Flipper briefly and wrote him a letter of warning and encouragement. Smith’s public battles against racism won him Black community support but cost him his commission.

Photo by Sepia Times/Getty Images

When Flipper graduated and was commissioned at the rank of second lieutenant, he became one of the most famous Black figures in the United States. At the age of 22, he published his autobiography, The Colored Cadet at West Point, solidifying his celebrity status.

Yet within the pages of this autobiography Flipper described just how differently he perceived himself from the other embattled Black cadets who preceded him, particularly Smith. Flipper was critical of Smith for being too public about his treatment and openly rejected the idea of ever being a professor at any of the Black colleges or universities.

Flipper did not want to be seen as a racial activist and concluded his story with praise and appreciation for his time at West Point, despite the bitter isolation he experienced.

Assigned to the 10th Cavalry, Lieutenant Flipper distinguished himself as an engineer. His surveys and roadbuilding in the Southwest often outperformed those of his white peers, showcasing both skill and grit.

Yet in September 1881, accusations of embezzlement upended his military career. While acquitted of the principal charge, he was convicted for a minor paperwork violation and, on January 30, 1882, was dishonorably discharged for “conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.”

His conservative politics—publicly rejecting “racial uplift” orthodoxy in his autobiography—meant that few in the African American press rose to defend him.

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Flipper’s post-military career proved just as successful as his military one. He served as an agent for the Department of Justice in the Court of Private Land Claims for several years.

His work and expertise in mining along the Mexican border, along with his fluency in Spanish, made him the ideal candidate to do intelligence work for Senator Albert Fall and the Senate subcommittee on Mexican Affairs during the Mexican Revolution of 1912.

All the while, Flipper lobbied continuously to clear his name. Simultaneously, he wrote letters to the Black press criticizing Black soldiers anytime the white press attacked them for standing up against Jim Crow racism. In his second unpublished autobiography, which contains several letters, Flipper wrote to a friend in 1937 that he opposed the Federal anti-lynching law because he believed it to be unconstitutional.

Flipper died on May 3, 1940, still burdened by his dishonorable discharge. He would be vindicated: in 1976, he received an honorable discharge, and in 1999, President Bill Clinton officially pardoned both Flipper and Smith.

Flipper’s life—a study in contradictions of loyalty, honor, and identity—remains a powerful testament to perseverance. His story challenges us to rethink heroism, recognize the costs of dissent, and honor the full complexity of America’s first Black West Point graduate.

Learn More:

McGovern, Rory, and Ronald G. Machoian. Race, Politics, and Reconstruction: The First Black Cadets at Old West Point. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press, 2024.

Donaldson, Le’Trice D. Duty Beyond the Battlefield: African American Soldiers Fight for Racial Uplift, Citizenship, and Manhood, 1870–1920. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2020.

Henry Flipper, The Colored Cadet at West Point.

Robinson, Charles. The Court Martial of Henry O. Flipper. El Paso: Texas Western Press, 1994.

Harris, Theodore D., ed. The Black Frontiersman: The Memoirs of Henry O. Flipper. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1997.