Photo by Rapho Guillumette/Archive Photos/Getty Images

The conventional history of the Civil Rights Movement details a series of legal victories from 1954 to 1968 that improved access to voting rights, economic opportunity, and social participation for African Americans.

A lesser-known aspect of Civil Rights activism is that the struggle for domestic social progress was inseparable from international political movements. Civil Rights activists often looked abroad to form partnerships with other marginalized communities, build moral and material support for their causes, and develop strategies to pursue their goals. The American Civil Rights Movement is a human rights struggle on an international stage.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

Federal district judge Thurgood Marshall had been sympathetic to the Kenyan decolonization struggle in the 1950s and he had defended African students as a lawyer for the NAACP. In 1960, Marshall participated in the first of three Lancaster House Conferences that ultimately produced the first constitution of independent Kenya.

At the 1960 Lancaster House Conference, Marshall drafted a “Kenyan Bill of Rights” that protected Kenyan minorities (White, Asian, and African) from discriminatory treatment. Jomo Kenyatta, inaugural president of post-independence Kenya, embraced Marshall’s view of equality under the law during the early days of his administration.

By July 1963, Kenya achieved full independence from Britain, and Kenyatta invited Marshall to witness the practical impact of the earlier constitutional debates. Here the two men share a light moment during Marshall’s short visit to Kenya.

Marshall’s legal framework for justice and equality in independent Kenya articulated the vision of social justice that guided his legal career in the United States.

Photo by Pictorial Parade/Archive Photos/Getty Images

In 1963, the Organization for African Unity (OAU) formed to establish mutual support and consolidate resources among an increasing number of newly formed African nations. Civil Rights activist and Muslim minister Malcolm X (left) speaks with an unidentified man at the African Summit Conference in July 1964, the second gathering of OAU delegates.

Malcolm X petitioned the OAU to denounce the United States for its history of racial violence, discrimination, and bigotry. He insisted that the United Nations declare that America’s racial history constituted a crime against humanity. He further argued that continental and diasporic Africans faced a common struggle to secure human freedom in the presence of imperial and colonial governments. His condemnation of the racial violence of the United States before the international community generated the ire of the U.S. Department of State.

This image captures Malcolm X’s evolving vision of the relationship among political activism, racial progress, and Muslim piety. By late 1963, Malcolm X’s departure from the Nation of Islam and participation in the Hajj led to his newfound faith that racial harmony was possible through Islam.

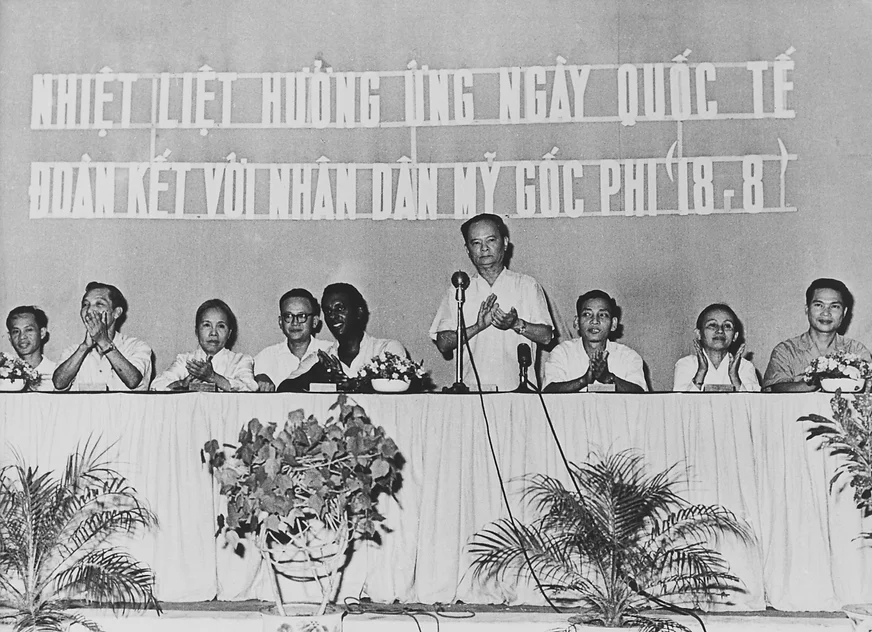

Photo by Rapho Guillumette/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Kwame Ture (previously known as Stokely Carmichael) appeared in Hanoi, to celebrate the 1967 International Day of Solidarity with members of the Black Panther Party. This ceremonial event reflects the global expansion of U.S. civil rights activism to encompass not only Africa but also alliances with developing nations in Asia and South America.

Ture’s appearance in Hanoi deepened the Afro-Asian affiliation that had begun nearly a decade earlier at the 1955 Bandung conference. Black Power activists ran tremendous risks participating in high-profile gatherings with communists in the global south.

In the case of Kwame Ture, along with activists Essie and Paul Robeson, the United States withheld passports to prevent their involvement in socialist causes throughout the decades of the Cold War.

Each of these three photographs captures the internationalism of American civil rights activists in the 1960s. Civil rights leaders understood that their local concerns gained recognition, authority, and legitimacy by attracting international press and collaborations.

The activism of the Civil Rights era included demands for African Americans’ citizenship rights and denunciations of America’s role as an imperial and colonial force across the world. African Americans also contributed their activist labors to support anticolonial struggles across continental Africa. These efforts at coalition building provided a playbook for contemporary social movements to convey their local struggles within a much broader community of international support.

Listen to the author:

Learn more:

George Breitman ed., Malcolm X Speaks: Selected, Speeches and Statements (Grove Press, 1990)

Mary L. Dudziak, Exporting American Dreams: Thurgood Marshall’s African Journey (Princeton University Press, 2011)

Nico Slate, ed. Black Power Beyond Borders: The Global Dimensions of the Black Power Movement (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012)