Photo by Archive Photos/Stringer/Getty Images

The coming of the Civil War brought the hope of liberation to millions of enslaved people.

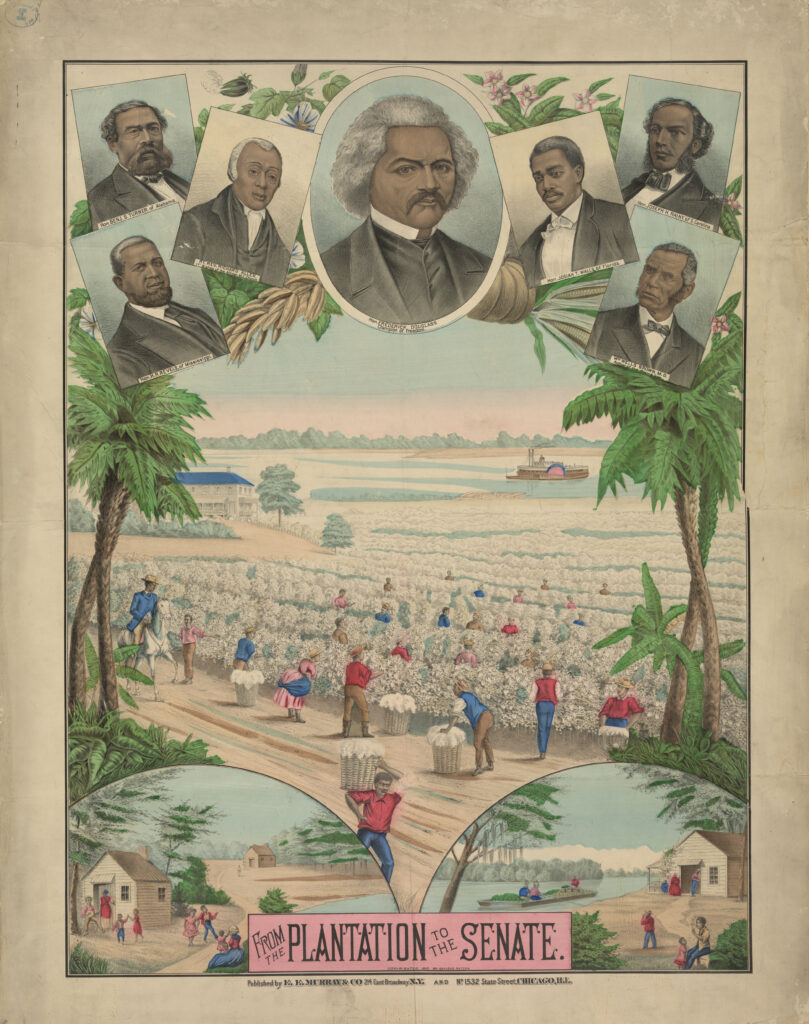

By the middle of the war, the Union had begun to see dismantling slavery and recruiting Black soldiers as necessary to victory. Individuals like Frederick Douglass made it clear that, with the end of slavery in sight, securing civil rights for the newly emancipated was crucial.

In 1863, Douglass proposed that formerly enslaved Blacks, if given the vote, would become the U.S. government’s “best protector against the traitors and the descendants of those traitors who will inherit the hate, the bitter revenge which shall crystallize all over the South, and seek to circumvent the government that they could not throw off.” The nation would need each of them “to uphold in peace, as he is now upholding in war, the star-spangled banner.”

Douglass, like many others, made the case that the ability of Black people to protect their rights and freedoms won in war depended on their right to shape politics and the law at the polls in peacetime.

Photo by Archive Photos/Stringer/Getty Images

When the 3rd United States Colored Troops (USCT) participated in capturing Fort Wagner, South Carolina in September 1863, among them was a twenty-year-old formally enslaved man named Josiah T. Walls.

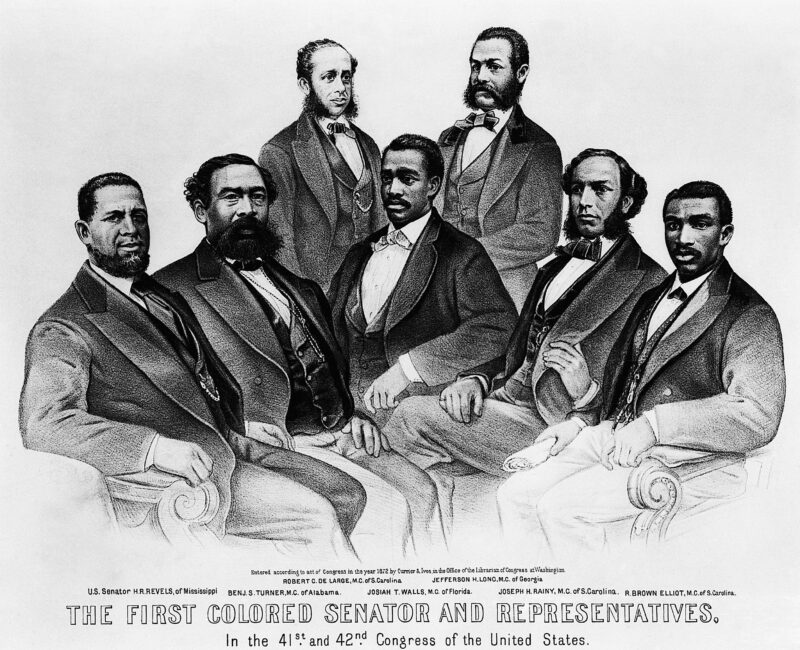

Walls, pictured in the above image to the right of Frederick Douglass (center), settled in Florida at the end of his military service and entered politics, eventually becoming one of the first Black men to serve Florida in the House of Representatives.

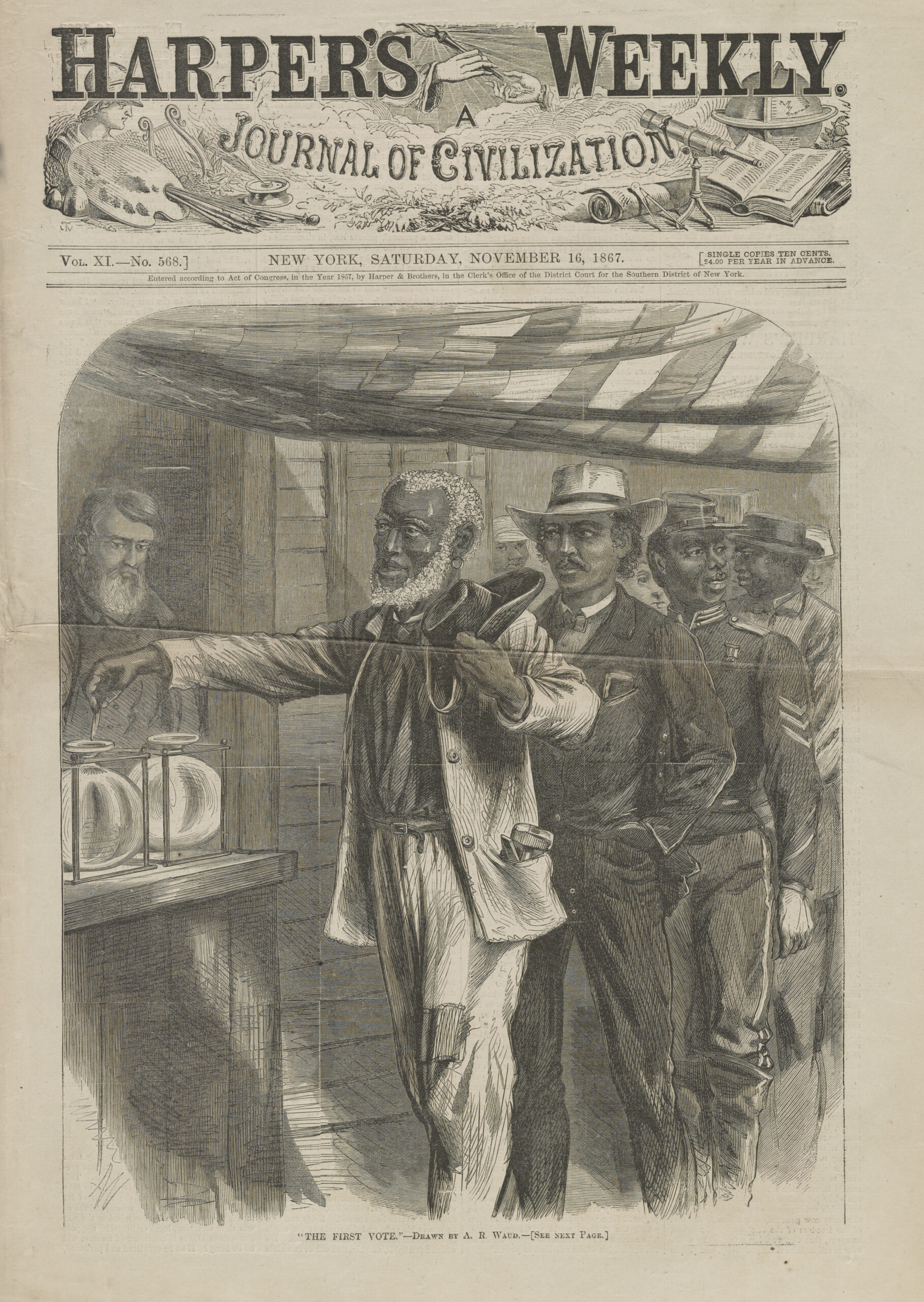

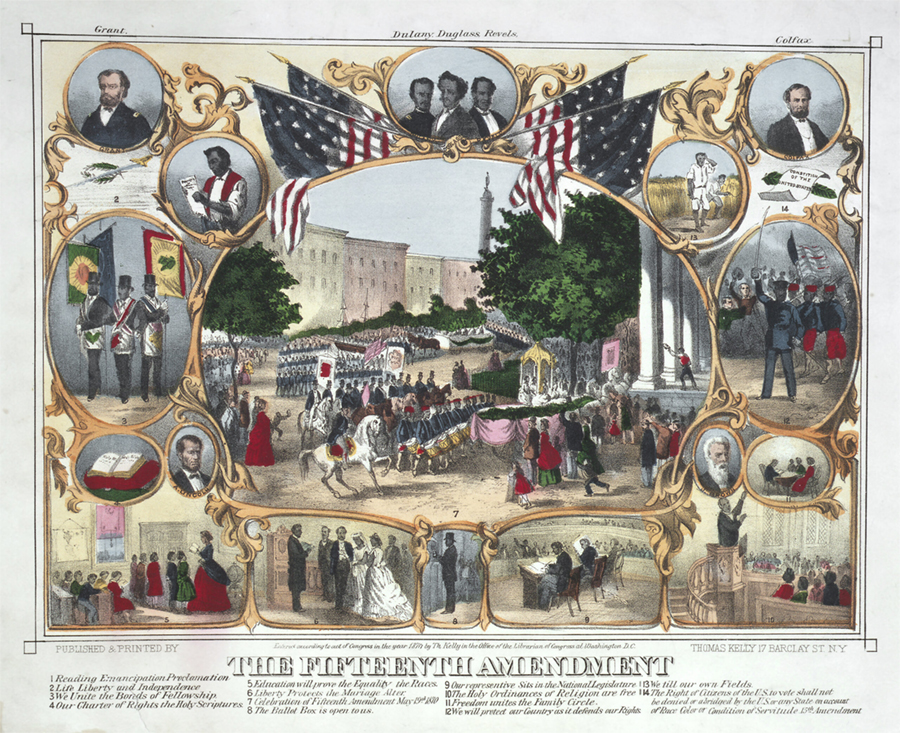

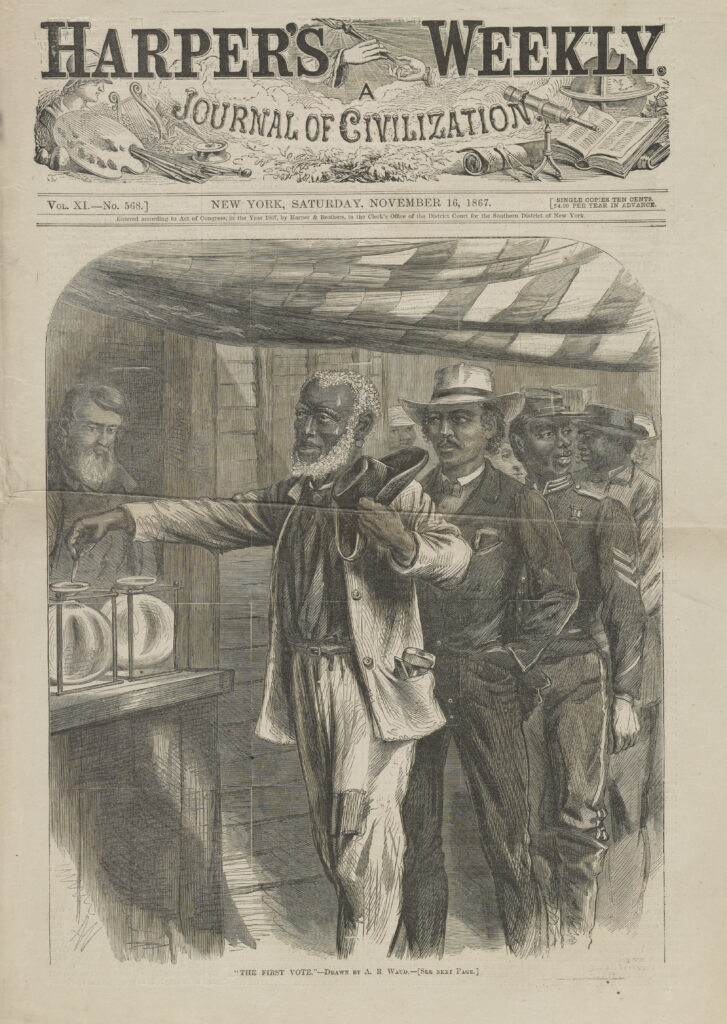

Before the 15th Amendment—celebrated in the image below, which guarantees citizens’ right to vote, regardless of “race, color, or previous condition of servitude”—took shape, the Reconstruction Act of 1867 forced former Confederate states to enfranchise all males before they could be readmitted to the Union.

Photo by Archive Photos/Stringer/Getty Images

Galvanized by the new laws, Black men by the thousands ran for public office both locally and nationally. Walls represented a trend of individuals who had passed through the crucible of war and emancipation and seized the opportunity to shape politics and the law to protect newly gained freedoms and rights for Blacks.

Born into slavery in Winchester, Virginia, on December 30, 1842, Walls was forced to be the private servant of a Confederate artilleryman at the onset of the Civil War. In May 1862, he fell into Union hands and was sent to Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where he received some education and enlisted in the 3rd United States Colored Troops.

The 3rd USCT was mustered into service at Camp William Penn, near Philadelphia, along with ten other Black regiments. In late Summer 1863, the regiment was sent south to participate in the siege and capture of Forts Wagner and Gregg.

By early 1864, the regiment was in Florida. Walls proved a commendable soldier and eventually reached the rank of sergeant by the time he mustered out in October 1865 with the 35th USCT.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

Walls, centered above among other early Black Congressional and Senate representatives, remained in Florida at the end of the war, worked at a sawmill on the Suwannee River, and later taught with the Freedmen’s Bureau.

His first steps into a political career came in 1868 when he represented Alachua County in the Florida constitutional convention. He was elected to the state senate along with four other freedmen in January 1869. He then served three terms in Congress from 1871 to 1877, all against constant challenges from white supremacists.

Despite election challenges, Walls represented the formerly enslaved, who at the time were coping with unemployment and substandard education. On the state level, he pushed for compulsory and racially equitable public education. He promoted Florida as a mecca for tourism and farming to elevate the economic well-being of the state.

This famous image from Harper’s captured the dignified gravity with which Black men, like Walls, conducted themselves as they exercised the voting rights they thought had been enshrined in the Constitution.

However, Walls eventually stepped back from his political career after losing his bid for state senate in 1890. The fundamental laws that allowed his election disintegrated as Jim Crow was set in place.

While he represented a small group of Black men who became involved in politics, he was joined by thousands nationwide who played a part in shaping their communities through the vote and setting an example for what voting equality could mean.

Learn More:

Eric Foner, Freedom’s Lawmakers: A Directory of Black Officeholders During Reconstruction

Philip Dray, Capitol Men: The Epic Story of Reconstruction Through Lives of the First Black Congressmen

Carol Anderson, One Person No Vote: How Voter Suppression is Destroying our Democracy

Glory [film 1989]