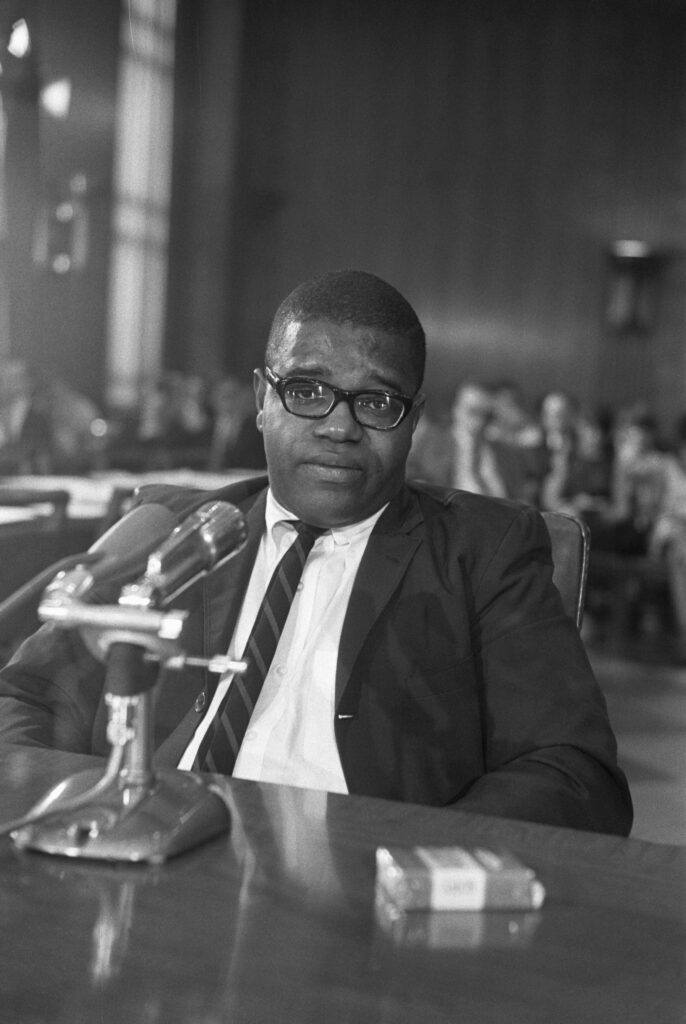

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

In this photograph, writer Claude Brown sits before a microphone in Room 1202 of the New Senate Office Building on Capitol Hill on August 29, 1966. He was there to give testimony about the growing “urban crisis” in America. For the third summer in a row, the nation’s cities had been rocked by uprisings of mainly poor, Black residents. Brown appears worried, his brow furrowed and eyes slightly downcast.

Despite his serious expression, Brown had been asked by Abraham Ribicoff, chair of the Senate Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization, to offer his “upbeat, affirmative” perspective.

Brown was the author of Manchild in the Promised Land, an autobiographical novel, released in 1965. In Manchild, he described growing up in Harlem during the 1940s and 1950s and his introduction at a young age to the world of gangs, junkies, pimps, and prostitutes.

His frequent run-ins with the law and his time in juvenile correctional institutions set him on a path that seemed likely to land him in prison. However, Brown chose to pursue education, moved to Greenwich Village, and went to night school to obtain a high school diploma. By the time this photograph was taken, he had earned a degree from Howard University and was about to start law school.

Manchild offered many white readers a glimpse into a world they little knew. Brown’s descriptions of the violence he encountered from a young age—he was shot during a robbery at 13 and saw another boy thrown off a roof on 149th Street—were shocking. And yet, Ribicoff noted, in Manchild he told his story “without bitterness, self-pity, or rancor.” Brown was affable, not angry.

Moreover, he appealed to white liberals such as Ribicoff because he embodied the promise of a liberal society: that a Black child raised in a place like Harlem could succeed on the terms of white society, even if that success remained out of reach for most others. Against all odds, according to Ribicoff, Brown had “made it.”

Understanding that his was an exceptional case, Brown brought his childhood friend Arthur Dunmeyer to testify alongside him. Dunmeyer, he said, was “more of a typical ‘manchild’” than himself: a grandfather at age 30 who had done time at Sing Sing and Attica. Dunmeyer represented the path that Brown might have gone down had he not left Harlem to pursue an education.

In their testimony, Brown and Dunmeyer described crime in Harlem—from sex work to illegal gambling to stickup artistry—as the way that people who were denied economic opportunity found means to participate in the consumer society of Cold War America. With “no doors really open to him,” how else could a man afford a nice suit and “a big Cadillac?” How else could a woman give her kids “the things that TV says that they should have?”

If anything, the pair argued, the hustles that many Harlem residents used to get by testified to their ingenuity. Those who “had a sheet on them”—that is, had a felony record—were shut out of the legitimate economy. Congress should pass a law, they suggested, to open government jobs to those convicted of felonies who had served their time. This, they insisted, “would stop the vicious cycle.”

Brown and Dunmeyer also criticized the few social services that were available in Harlem. In their view, anti-poverty programs were driven by detached experts—“the psychologists and the sociologists”—with little interest in learning about the everyday lives of people in places like Harlem.

Instead, they pushed for localized poverty relief programs that would be driven by the expertise and ability of the very people they were meant to serve. “You have to go all over,” Dunmeyer insisted, “and look at every group, every situation for what it really is.”

In this way, Brown and Dunmeyer’s testimony reflected the mandate in President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty programs for “maximum feasible participation of the poor.” Indeed, the Model Cities Program, announced in early 1966 and signed into law months after this hearing, captured some of the spirit of their proposal. However, the program was underfunded and ran into a slew of criticisms before being discontinued in 1974.

Throughout the decades that followed, life in Harlem—along with predominantly Black urban areas throughout the country—grew more difficult.

The supposed failure of War on Poverty programs to solve the entrenched problem of inequality was used to justify shifting federal funding away from cities. At the same time, approaches to policing and incarceration became increasingly punitive.

As Black life became criminalized in new and harsher ways, more and more would find themselves locked in the “vicious cycle” that Brown and Dunmeyer had described.

Learn more:

Claude Brown, Manchild in the Promised Land, Reprint edition (New York: Touchstone, 2011).

Federal Role in Urban Affairs: Hearings Before the United States Senate Committee on Government Operations, Subcommittee on Executive Reorganization (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1966).

Thomas Sugrue, The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit, Revised edition (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2014).