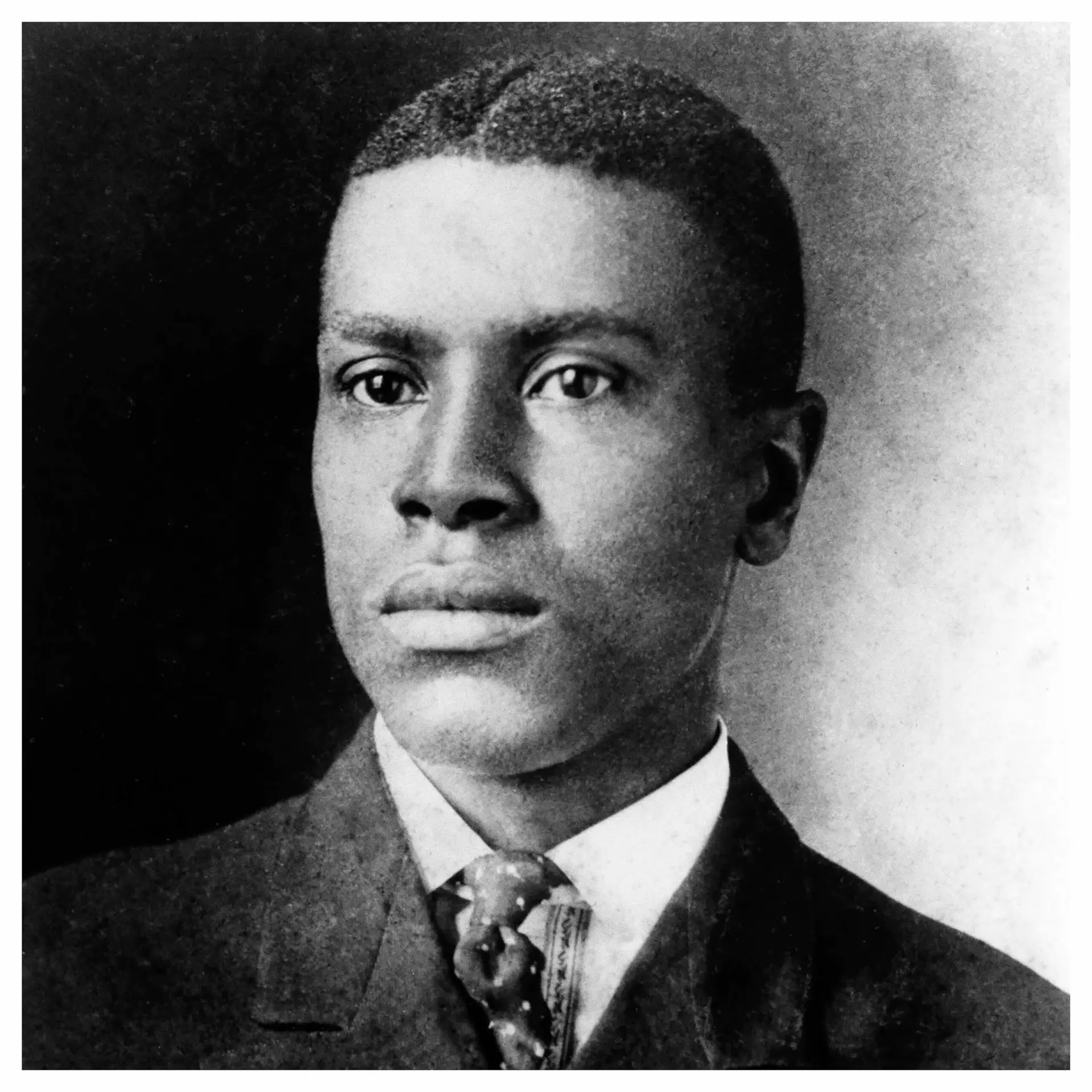

Photo by John Kisch Archive/Getty Images

Oscar Micheaux was a maverick and an innovator who possessed an extraordinary creative drive. An author and one of the earliest African American filmmakers, Micheaux (shown here in his youth) wrote seven novels and produced some 40 films.

Born in southern Illinois in 1884 to two formerly enslaved parents, Micheaux’s life was a series of migrations, new beginnings, and transitions—each one a learning experience. After moving to Chicago at 18, the future director worked in multiple jobs, including in the stockyards, as a shoe shiner, and as a Pullman porter.

A supporter of Booker T. Washington and a practitioner of racial uplift, Micheaux demanded that Black people spend their money well and create enterprises to support their lives and communities. He advocated a “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” attitude in the Black press, calling for the community to move West and take advantage of pioneering opportunities. He embodied uplift in the way he dressed and carried himself and in his actions.

Though he would return to the city later in life, Micheaux was drawn to the countryside. Taking advantage of landownership opportunities in the West, the young Micheaux spent nearly a decade on a western adventure, moving to South Dakota in 1904 to work a homestead.

Attempting to live self-sufficiently, Micheaux faced harsh weather and failing crops. His marriage to Orlean McCracken, who badly missed city life in Chicago, was soon to be over in a very public and nasty divorce.

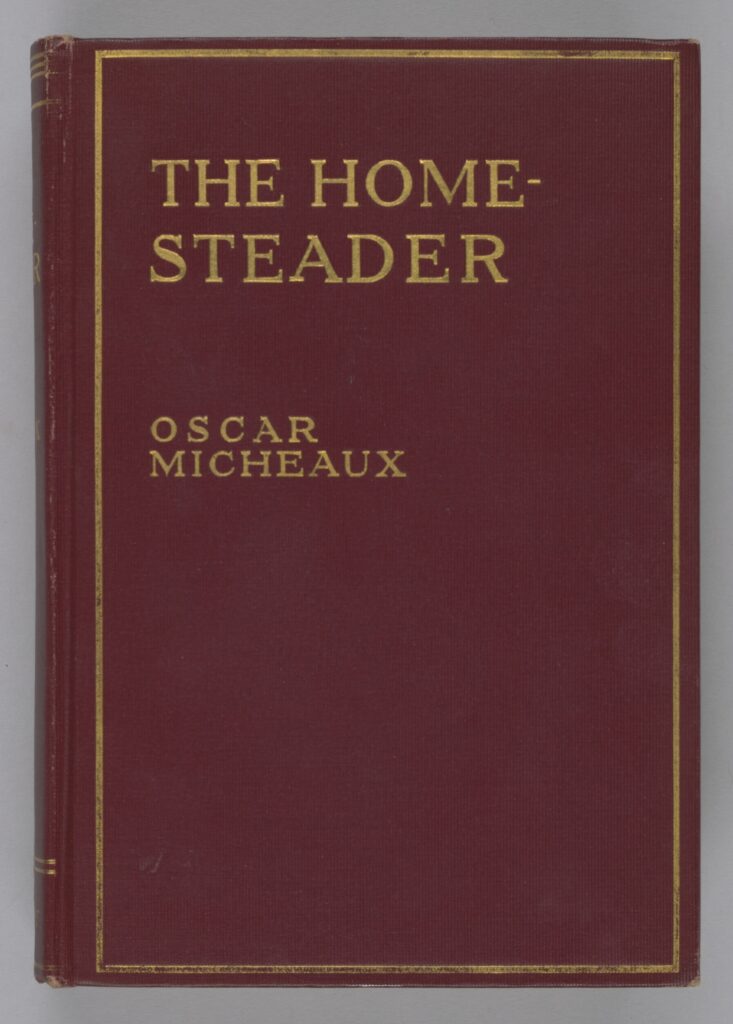

Photo by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images

By the early 1910s, Micheaux was drawing upon these experiences to write his novels. His first, The Conquest: The Story of a Negro Pioneer, published in 1913, The Forged Note, published in 1915,and his third, The Homesteader (pictured here), published in 1916, are all autobiographical texts detailing his life in South Dakota.

Convinced of the story-like nature of his own life, Micheaux took his failure and repositioned it for potential commercial success, telling his life story as a homesteader through a lens of hard work, persistence, and even a bit of romance. Though not best sellers by any means, Micheaux’s novels afforded him comfortable living.

The Homesteader, which Micheaux funded and published through fundraising from his white neighbors in South Dakota and distributed through relentless self-promotion, served as the basis for his first film. Released in 1917, the film allowed Micheaux to move his life story (his “biographical legend,” as some scholars say) to the big screen.

The origin of this film and his shift to filmmaking reflect Micheaux’s drive and ambition. He was approached by an employee of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, a popular enterprise that produced race films, to adapt The Homesteader.

A relatively new and potentially lucrative development dating to around 1910, race films were those by, for, or about African Americans, seeking to fill a void that the mainstream film industry was not necessarily interested in. With no film experience whatsoever, Micheaux rejected Lincoln’s offer. Instead, he created the Micheaux Film and Book Company and began fundraising among his white neighbors again—all before he even wrote the script.

With probably no more than middle school education, Micheaux possessed a business cunning that kept his films in theaters (usually in those spaces or at showings specifically for Black audiences) despite some resistance from censors and critics.

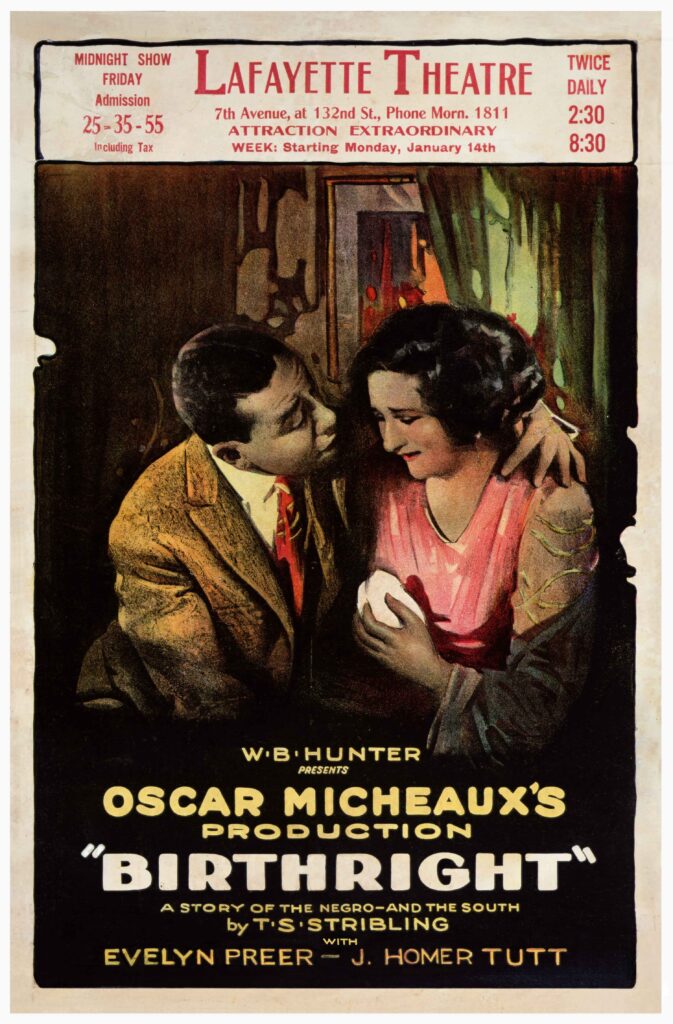

Photo by John Kisch/Getty Images

Birthright (1924), for example, was flagged by censors in New York, Chicago, and Virginia for its allusions to interracial affairs and bold criticisms of southern racism. A promotional poster (shown here advertising the film’s Black leads) only hints at the emotional turmoil its main female character, Cissie Dildine, experiences in the wake of threatened sexual assault and police violence in a segregated Tennessee town.

In cases such as this, Micheaux either negotiated with the censors or, taking a radical option to defy restrictions on his material, simply showed the films without formal licensing and review—yet another display of his relentless determination.

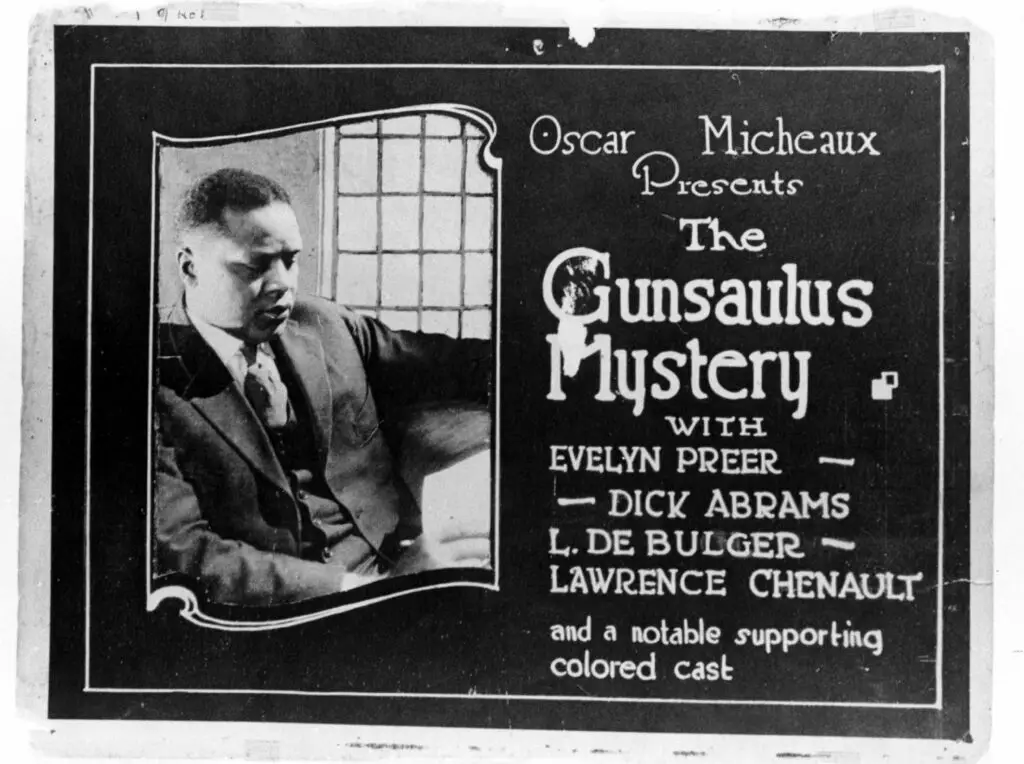

His advertising materials usually played up the fact that his films featured all-Black casts. He especially emphasized well-known performers such as Evelyn Preer or Laurence Chenault (each advertised in the posters here). To draw in a crowd and drum up anticipation, Micheaux toyed with sensationalism and highlighted the melodrama of his films.

Photo by Smith Collection/Gado/Getty Images

The films, too, spoke to their audiences and historical moment. A committed showman with a penchant for moralizing, Micheaux’s films often hinged on well-known or ongoing controversies or hotly debated topics within the Black community.

The Gunsaulus Mystery (1921) claimed to rely on the trial of Leo Frank, a Jewish man lynched after being accused of raping and murdering a woman in Georgia in 1915. Birthright’s story, which centered the question of Black higher education, also pushed the boundaries of acceptability by boldly insinuating a white man’s rape of a Black woman.

It is no surprise, given his dogged commitment to Black storytelling, that Micheaux made the transition from silent to sound films in the 1930s. His career continued until his death in 1948, though his popularity significantly waned because of his reluctance (or inability) to adhere to Hollywood standards.

An independent filmmaker without access to the funds and support of the Hollywood system, Micheaux always operated with a limited budget and small staff (which included his second wife, Alice B. Russell).

His legacy, fraught as his career, was that of a man bound by his principles with an any-means-necessary approach to his work. Though all but three of his silent films are lost, and his sound films are generally neglected, Micheaux’s impact on the history of Black filmmaking is indelible.

Learn More:

Charles Musser, Jane Gaines, and Pearl Bowser, eds. Oscar Micheaux & His Circle: African American Filmmaking and Race Cinema of the Silent Era (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001).

Jane Gaines, Fire & Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001).

J. Ronald Green, Straight Lick: The Cinema of Oscar Micheaux (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000).

Charlene Regester, “Emerging from the Shadows: Alice Burton Russell—African American Film Producer, Actress, and Screenwriter,” Film History 32, no. 1 (2020): 127-155.

Patrick McGilligan, Oscar Micheaux: The Great and Only: The Life of American First Black Filmmaker (New York: Harper Perennial, 2008).

Pearl Bowser and Louise Spence, Writing Himself into History: Oscar Micheaux, His Silent Films, and His Audiences (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2000).