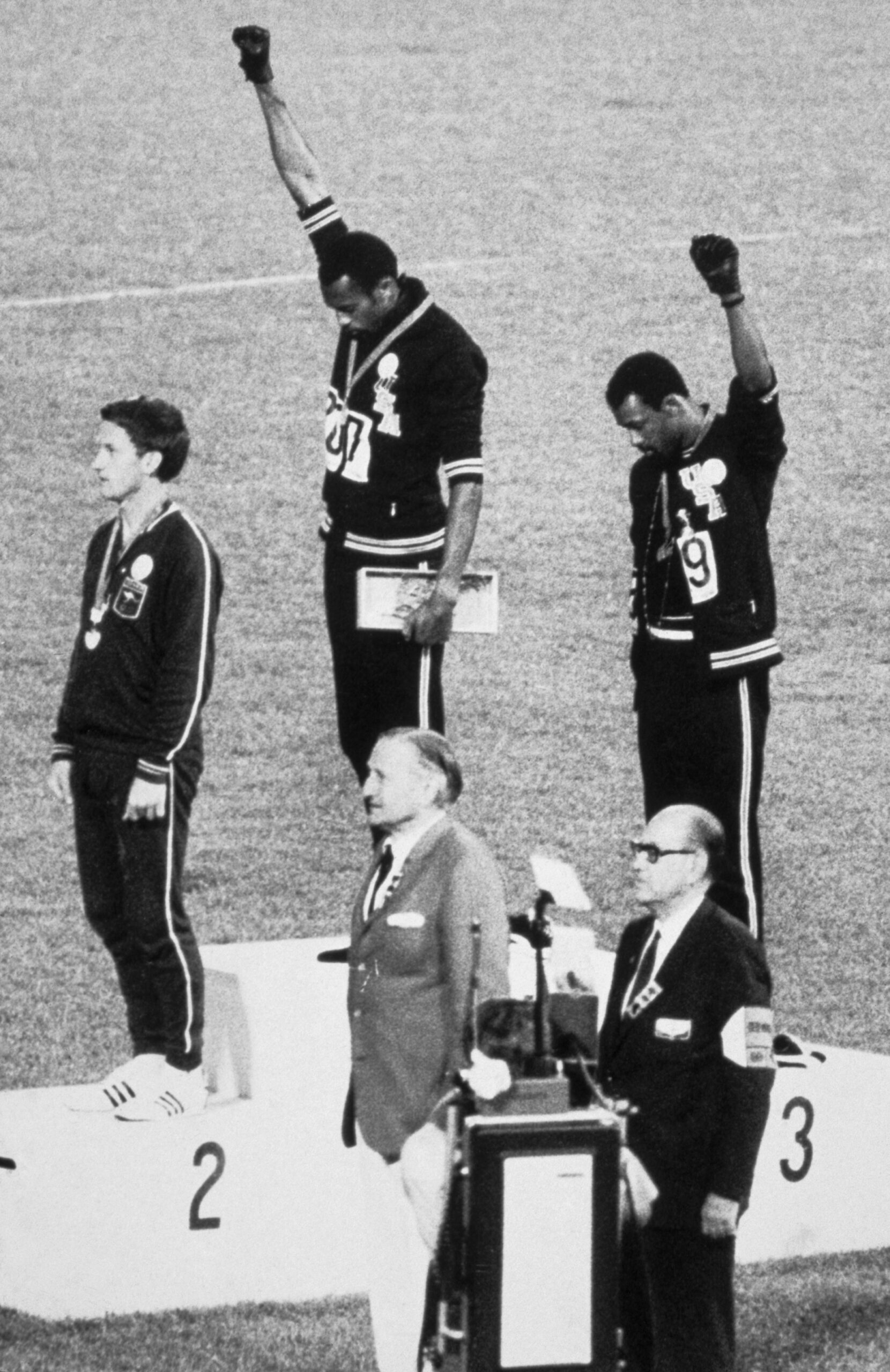

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

On October 16, 1968, after finishing first and third respectively in the 200-meter dash at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, Tommie Smith and John Carlos ascended the medal podium in black socks and thrust their black-gloved fists high into the night. Their act disrupted an American Cold War triumph and transformed it into an iconic moment of Black anti-racist protest.

The protest was seen by more than 80 million households around the world and shocked many. It represented an emergent Black Power Movement’s advocacy to have discrimination redressed by a state that interpreted Black protest as antithetical to its Cold War foreign policy goals.

The protest was a product of the Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), a Black Power campaign that proposed a boycott of the games to protest institutionalized racism. The campaign attracted significant international attention because of its Cold War implications.

Over the preceding three decades, Black athletes had become essential to U.S. competitiveness in international sports, dominating premier events like heavyweight boxing and sprinting. American nationalists and conservatives capitalized on their victories to suggest that the American way of life, capitalism, and democracy produced a superior citizenry.

Many of these same pundits also found it excruciating to admit that a boycott by Black athletes would doubtless result in the Soviets outscoring the U.S. in the medal count for the fourth consecutive games. Several politicians, including Robert Kennedy and Ronald Reagan, openly worried that poor performances at the Olympics damaged public support for the United States’ Cold War effort.

The boycott worried the U.S. State Department because it transgressed foreign policy propaganda that racism was declining in American society. The boycott was also widely debated because it contradicted “the myth of the Black athlete,” a widely accepted notion that the ever-increasing visibility of Blacks in team sports meant that racial equality was viable in American society.

In response to Soviet propaganda that highlighted the routine discrimination and violence Blacks encountered in the United States, and in its efforts to gain geopolitical allies among newly independent nations of color, the federal government disseminated a message that individuals with a sufficient work ethic achieved success in American society, regardless of race.

In the 1960s, the United States Information Agency regularly circulated media to the foreign press that portrayed Olympic medal winners like Cassius Clay and Wilma Rudolph as respected citizens. The State Department also sent Black athletes on some 60 goodwill tours abroad to showcase that development. The international media attention that the Olympics attracted assured that a boycott would present a serious challenge to U.S. foreign policy propaganda.

It was in this context that three Black student activists—Tommie Smith and Lee Evans, both world-class sprinters, and Harry Edwards, a former student athlete—organized the OPHR. Like other progressive groups, the OPHR faced state repression in part because of the Cold War implications. The mainstream media and sports establishment condemned the boycott as reverse racism and unpatriotic and dismissed Edwards as a raging “Black militant.”

Edwards countered by orchestrating events that kept the boycott newsworthy in the national media. For instance, in December 1967, he held a press conference featuring Martin Luther King’s boycott endorsement. The OPHR also gained international support by linking to the anti-apartheid movement that forced the Olympics to bar South Africa.

Edwards also adopted a militant façade that attracted international attention. Thus, an exasperated Sports Illustrated reporter concluded that Black activism could be a bigger problem at the games than Mexico City’s high altitude and extreme heat.

Behind the scenes, however, state repression caused the boycott to falter. The sports establishment attempted to prevent Carlos, Smith, and Evans from making the U.S. team. In the summer of 1968, each had to file protests to claim Olympic spots. They also were harassed by the state. COINTELPRO documents demonstrate that by March 1968, the FBI had targeted Edwards for “neutralization.” They received death threats, were harassed by local authorities, and lost jobs.

Although Lew Alcindor, the best college basketball player of his generation, chose to boycott the games in protest, most Black Olympians did not. As a result, in September 1968, just weeks before the games, the OPHR terminated its boycott campaign.

Nevertheless, Smith and a small number of Black Olympians decided that they would orchestrate their own individual protests. They concluded, as several activists did, that if racists believed that repression could stymie their protest, organized Black activism would only be met with more repression. Secondly, they shared Black progressives’ conclusion that advancing Black rights was as important, if not more so, than the United States’ foreign policy goals.

Thus, Smith led Carlos in their Black Fists demonstration. They stood on the podium in their socks to symbolize Black poverty. Smith wore a black scarf around his neck as a symbol of Black pride and Carlos wore a beaded necklace “for those individuals that were lynched, or killed and that no-one said a prayer for,” as he explained later. The silver medalist, Australian Peter Norman, joined the two Americans by wearing an OPHR badge.

Two days later, in an interview with Howard Cosell, Smith made it clear that he used his Olympic platform to interject Black concerns into the national discourse. He may have won a gold medal, but as he explained to Cosell, most Blacks’ lives remained circumscribed by institutionalized racism. Carlos was even more explicit when he explained that he could not subjugate Blacks’ concerns to the nation’s agenda.

For more than a decade following the protest, Black, leftist, and Third World activists adopted the clenched fist as an anti-imperialism identifier. Simultaneously, the state tried to suppress that meaning by harassing activist-athletes, and the mainstream media condemned the action to deter similar protests.

However, the dramatic gesture has outlived the criticism. In the five decades since that moment, posters, t-shirts, and postcards of the protest have been sold continuously in Black communities and in 2017, several athletes, most notably Colin Kaepernick, resurrected the gesture as a means of raising awareness of social justice issues.

Listen to the author: