Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

Ask an English fan of football (“soccer” to U.S. readers) to name an iconic image of sporting heritage, and there’s a good chance they will mention national team captain Bobby Moore, World Cup in hand, held aloft on the shoulders of his fellow players.

This famous photograph, taken shortly after England’s 4-2 final victory over West Germany in 1966, marks the only time the nation has won the biggest tournament in world football. With each passing year, the image carries more nostalgia. Only one member of the squad, Geoff Hurst, who stands immediately left of Moore in the picture, is still living.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

For many, the image recalls the passing of a hopeful moment. 1966 was a time of confidence. After the trauma of World War II, rationing, and economic stagnation, England was cool again. That year, Time Magazine declared London the “Swinging City,” Carnaby Street was the colorful center of fashion, and the Beatles and Rolling Stones were taking the world by storm.

Nothing symbolized this sense of renewed optimism better than three of the 1966 players: Moore, Hurst, and Martin Peters (just left of Hurst in the image). These three, captain and scorers of all of England’s goals in the final, played club football for West Ham United, a team from a working-class area of East London damaged badly by wartime bombing.

But if the photo from 1966 tells a story of England’s recovery, it obscures the key role played in that recovery by its Black population. To fill postwar labor shortages and rebuild a shattered country, 500,000 “Windrush” immigrants from its Caribbean and African colonies claimed nationality in Britain between 1948 and 1971.

None of this is evident from the World Cup photo, where every player, like the entire England squad, was white. Despite the profound importance of their labor to Britain’s larger sense of restoration in 1966, there would be no picture of a Black player in an official England team shirt until 1978 when Viv Anderson, the son of two Jamaican Windrush migrants, became the first to play for England (pictured below wearing an England jersey in 1978).

Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Five decades earlier, it might have been different. Anderson might have been the first to play for England, but he wasn’t the first to make the team. That honor fell to Jack Leslie in 1925. Born in 1901 to a Jamaican father and an English mother, Leslie reminds us that Caribbean migrant communities were a fundamental part of English society long before Windrush.

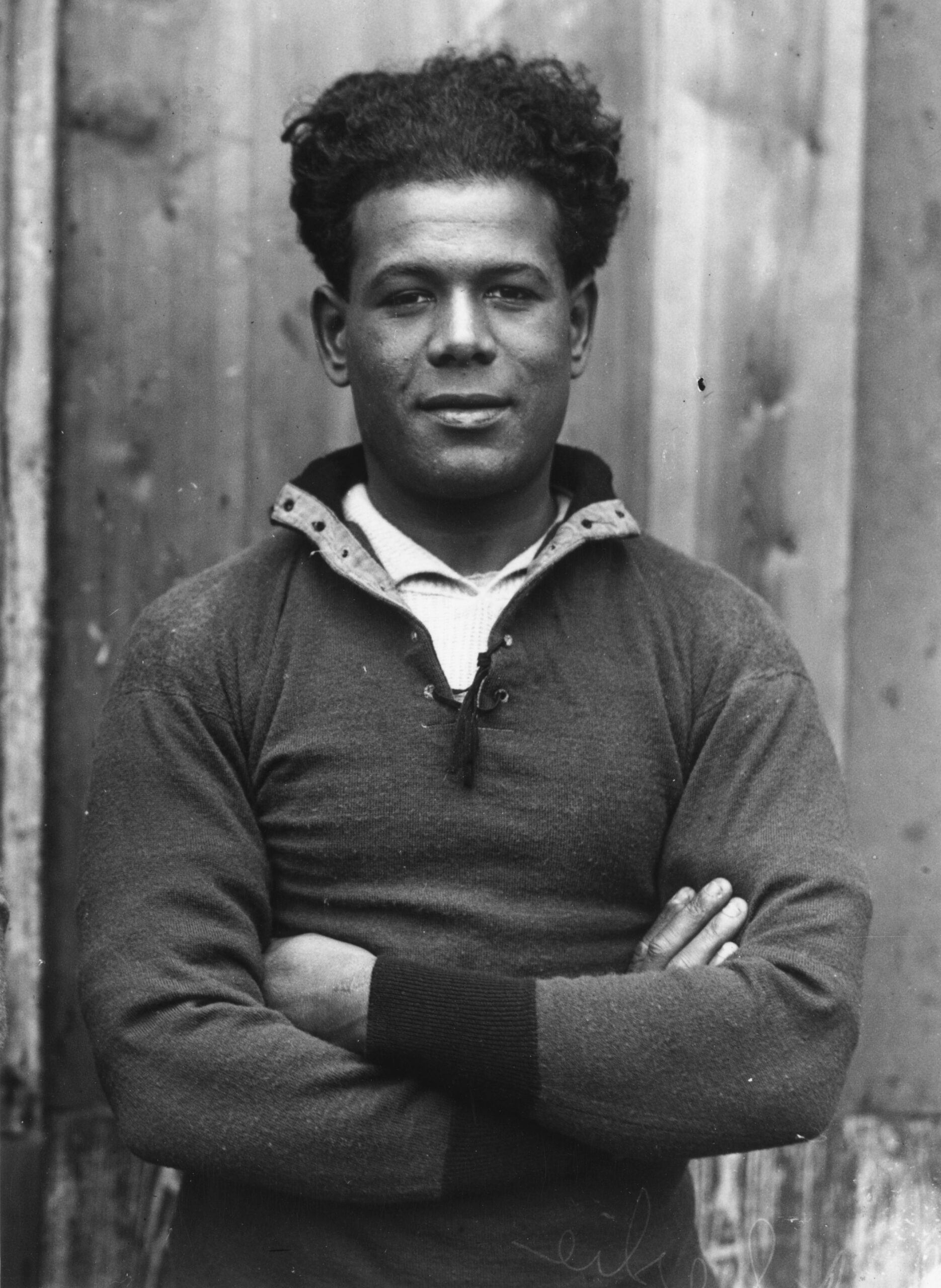

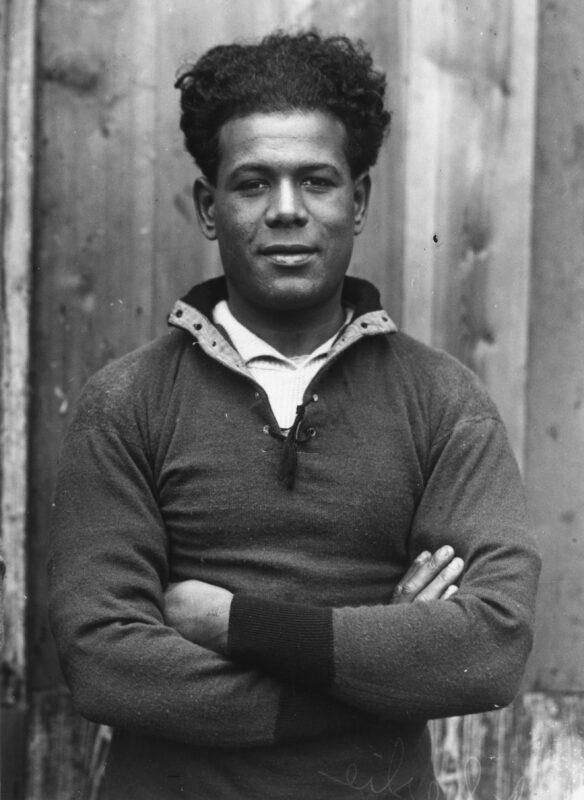

A prolific inside-left forward, Leslie (pictured below in 1922) scored over 250 goals for Barking Town. After being recruited by Plymouth Argyle in 1921, he scored a further 137. His form earned him a call-up from the England International Selection Committee for a match against Ireland.

The Tourquay Herald Express, assumed that “everyone” celebrated the announcement “with keen pleasure,” certain that Leslie “would win further honours” with England.

Leslie never got his chance. “Keen pleasure” was not felt by England’s players or the selection committee, many of whom were unaware of Leslie’s racial identity. Before the game took place, his name was removed from the squad list without official explanation.

Leslie knew the reason. Using common parlance of the time, he joked that “they must have forgot I was a colored boy.” While there is no photo of Leslie in an England shirt, there are pictures of him in Plymouth Argyle’s kit. This one from 1922, in which he looks straight at the camera with his arms folded, captures a sense of certainty in his ability.

In another from 1926, he appears smiling among his teammates, striding together toward a sign that reads “Second Division” (below, Leslie is third from the right). A reference to Plymouth’s impending promotion up the league, which owed much to Leslie’s goals, the image suggests Leslie’s confidence remained undented.

Photo by Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

After he retired from playing, at a time when professional footballers needed second careers to make ends meet, Leslie became the “boot boy” at his local team, West Ham United. There he cleaned the boots of the three World Cup winners Moore, Hurst, and Peters, who never knew about Leslie’s impressive footballing career, nor how close he had come to sharing the distinction of representing the nation.

What more apt metaphor could there be of how England’s sense of renewed optimism in the 1960s relied on the invisible labor of Black people?

Leslie’s death in 1988 went relatively unnoticed by the football world. But he was recognized posthumously in 2022 with a statue outside Plymouth Argyle’s stadium and an honorary cap—the traditional award England players receive for each match appearance—by the Football Association.

Yet this should not suggest football, or England, has resolved the racism that excluded Leslie from the team. While several Black players have played for England since Viv Anderson’s debut in 1978, they regularly experience racist abuse when the team loses.

After defeat to Italy in the 2021 European Championship, Marcus Rashford, Jaden Sancho, and Bukayo Saka were singled out for vitriol after missing penalties in the crucial shootout. When a white player, Harry Kane, missed an equally costly penalty in the World Cup the following year, he received nothing like the same treatment.

It is not hard to imagine that had Leslie ever missed a penalty for England, his experience would have mirrored that of Rashford, Sancho, and Saka. But if his 1922 portrait offers any clue to how he would have responded, it is also not hard to imagine that he too would have persevered, his belief unshaken in his remarkable talent as a footballer and his right to belong in the nation he called home.

Learn More:

Jacobs, Calum, ed., A New Formation: How Black Footballers Made the Modern Game (London: Merky Books, 2022)

Olusoga, David, Black and British: A Forgotten History (London: Macmillan, 2016)

Perry, Kennetta Hammond, London is the Place for Me: Black Britons, Citizenship and the Politics of Race (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016)

Tiller, Matt, Jack Leslie: The Lion Who Never Roared (Brighton: Pitch Publishing, 2023)