Photo by F. Roy Kemp/BIPs/Getty Images

On July 25, 1971, the New York Times declared Philadelphia the “graffiti capital of the world.” The city had not earned this moniker overnight. From approximately 1965 to 1985, Black teenagers like Dr. Cool No. 1, Tity Peace Sign, Cool Earl, Sexy Snake, Knife, and Cornbread, who proclaimed themselves “wall writers,” ignited a modern graffiti movement.

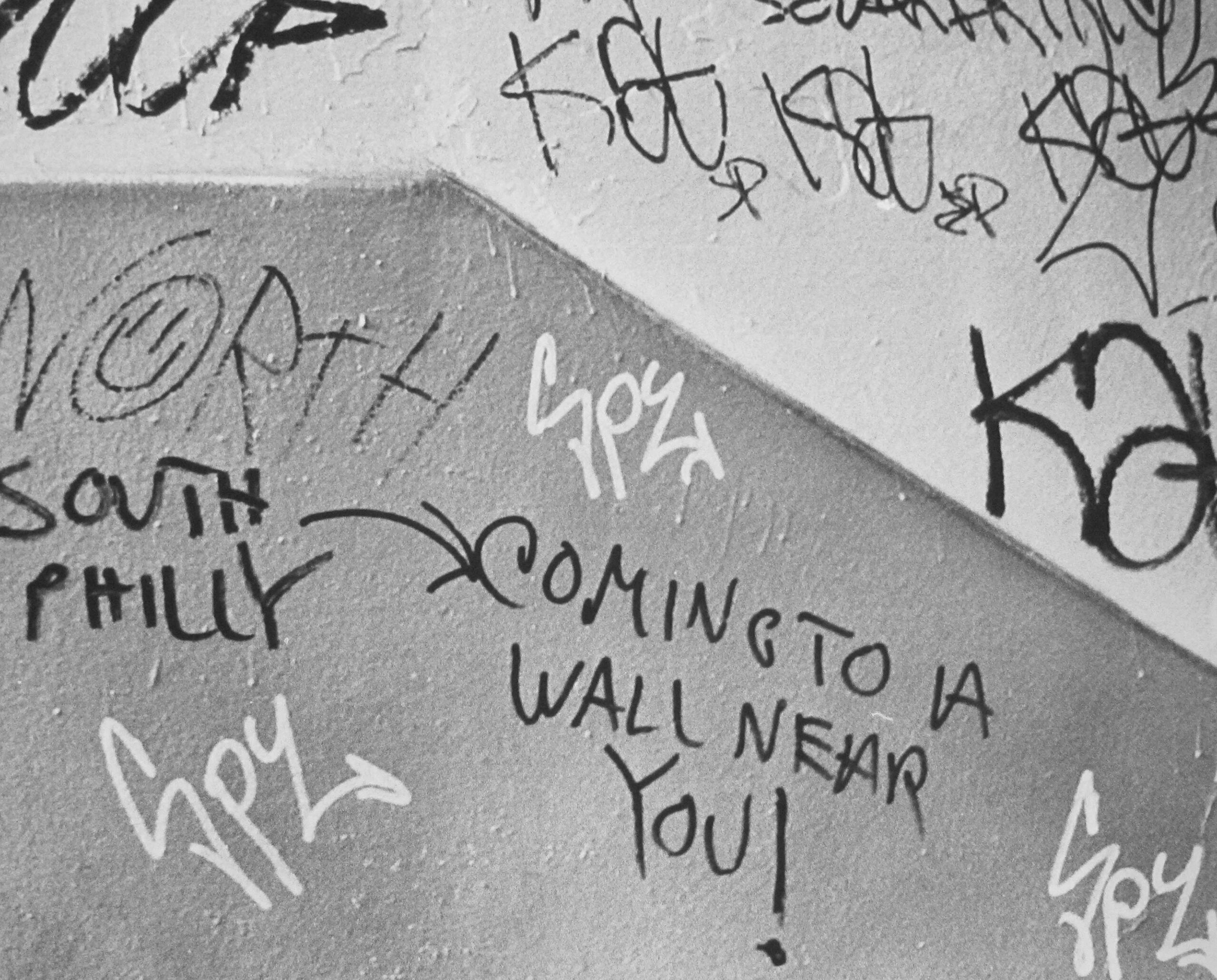

This 1975 image of a graffitied wall at Philadelphia’s 22nd Street trolley station demonstrates how youth not only tagged their names and neighborhoods, but also protest messages.

Photo by Jack Tinney/Getty Images

Two years earlier, in 1969, the New York Times had also declared Philadelphia the “gang capital” of America because its police department documented 70 gangs and the highest rate of gang-related violence in the country: 45 murders and 267 injuries. Some gangs used graffiti to document their members’ names and warn rivals to avoid their turf.

By the 1970s, Philadelphia’s poverty rate was 15.4%, and 200 gangs operated throughout the city, with 96% of members being Black males. Nevertheless, some frustrated Black teenagers who experienced urban decline refused to cope with life through gang activity and drug use. Instead, they chose graffiti.

In 1965, North Philadelphia teenager Darryl “Cornbread” McCray, the “godfather” of the modern graffiti movement, began “writing” in the Youth Development Center (YDC) where he served stints for disorderly conduct, shoplifting, trespassing, runaway, truancy, and vandalism. His tag name came from a Mr. Swanson, the head cook of the facility, who threw him out of the kitchen for badgering the staff to bake his grandmother’s style cornbread.

Cornbread started writing on walls with a magic marker and graduated to using spray paint on countless public spaces. Cornbread’s initial moment of notoriety occurred when he tagged “Cornbread Loves Cynthia” at bus stops and on neighborhood buildings to win the affection of his eighth-grade classmate at Strawberry Mansion Junior High School.

Between 1967 and 1971, Cornbread sought to gain a reputation citywide by tagging his name on buses, police cars, postal trucks, cabs, freight trains, the subway, a brand-new Holiday Inn, and “heaven spots” where someone could risk their life tagging, like a 30-story skyscraper under construction.

Although journalists, geographers, and everyday citizens often associated graffiti with blighted Black neighborhoods, the February 1971 gang-related murder of 17-year-old West Philadelphia teenager Cornelius “Corn” Hosey helped solidify the public’s belief that graffiti was linked to violent crime.

When Philadelphia journalists reported Hosey’s death in newspapers like the Inquirer, Daily News, and Tribune, they erroneously claimed Hosey was Cornbread. Cornbread later telephoned newspaper headquarters and the local Black radio station WDAS to inform them he was still alive and would be even more ambitious in his tagging.

Cornbread then tagged his name on the Jackson 5’s plane at the airport when they arrived for a concert and wrote “Cornbread Lives” on an elephant at the Philadelphia Zoo with spray paint.

Cornbread’s antics encouraged the police to develop a Graffiti Squad composed of 10 plainclothes officers that August to halt vandalism they claimed cost the city $2 million a year to remove. Police conducted stakeouts on streets and subway platforms to arrest juvenile graffiti writers. Within two years, the Graffiti Squad made 474 “vandalism” arrests and sentenced youth to probation and community service that involved graffiti cleanup.

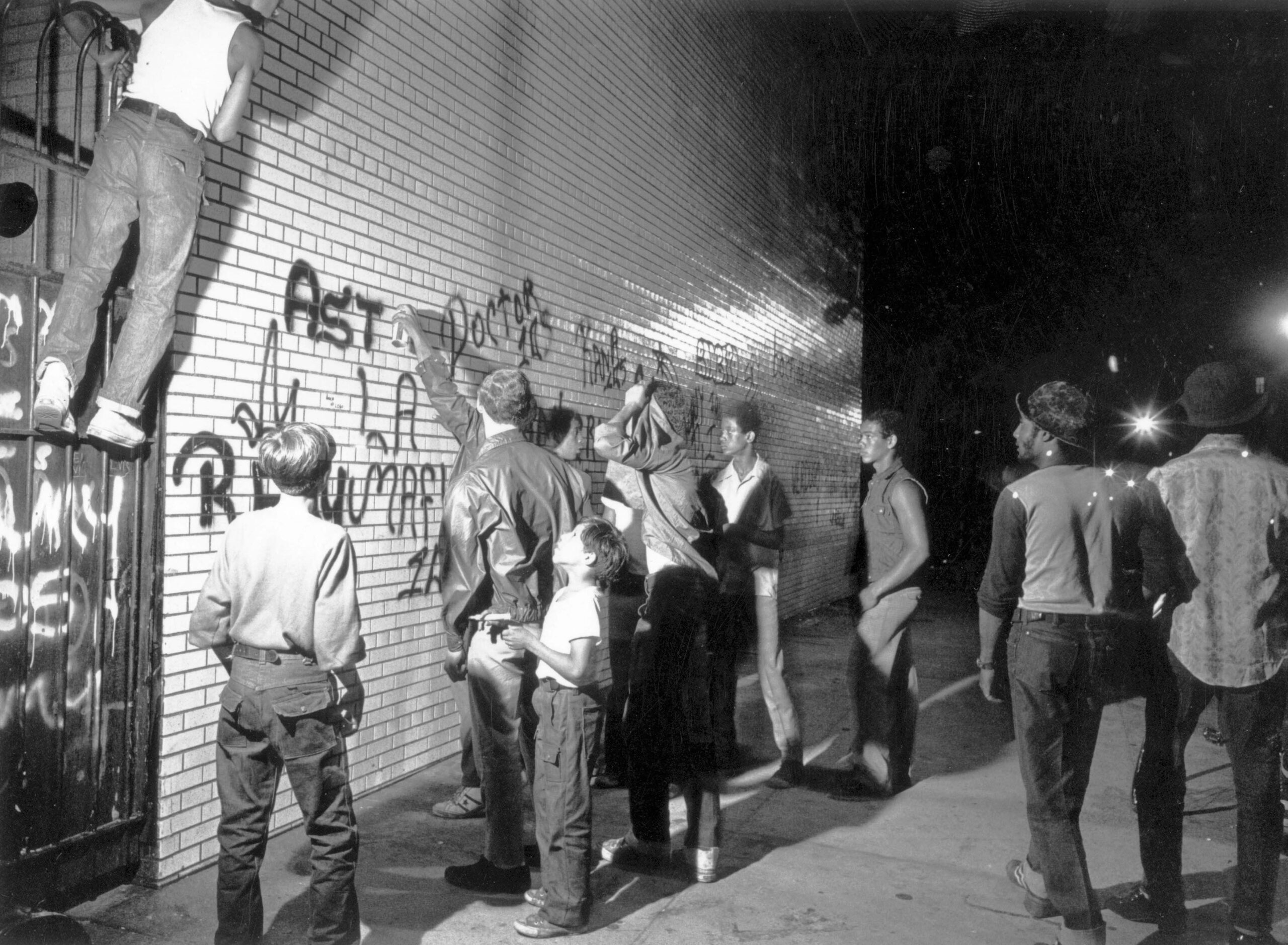

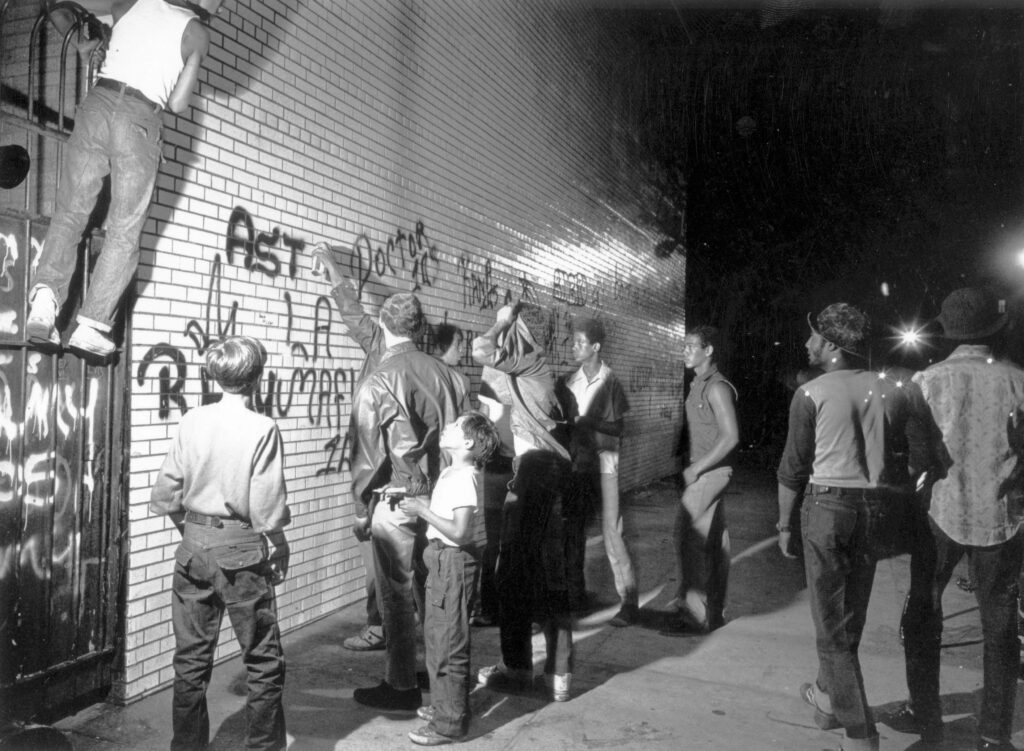

As 18-year-old Cornbread and several other graffiti writers considered “retirement” and pursued mainstream career paths as commercial artists, thousands of youths in Philadelphia and across America continued to tag as individuals or in groups of up to 50 (as seen above in this July 1972 image of youth in New York).

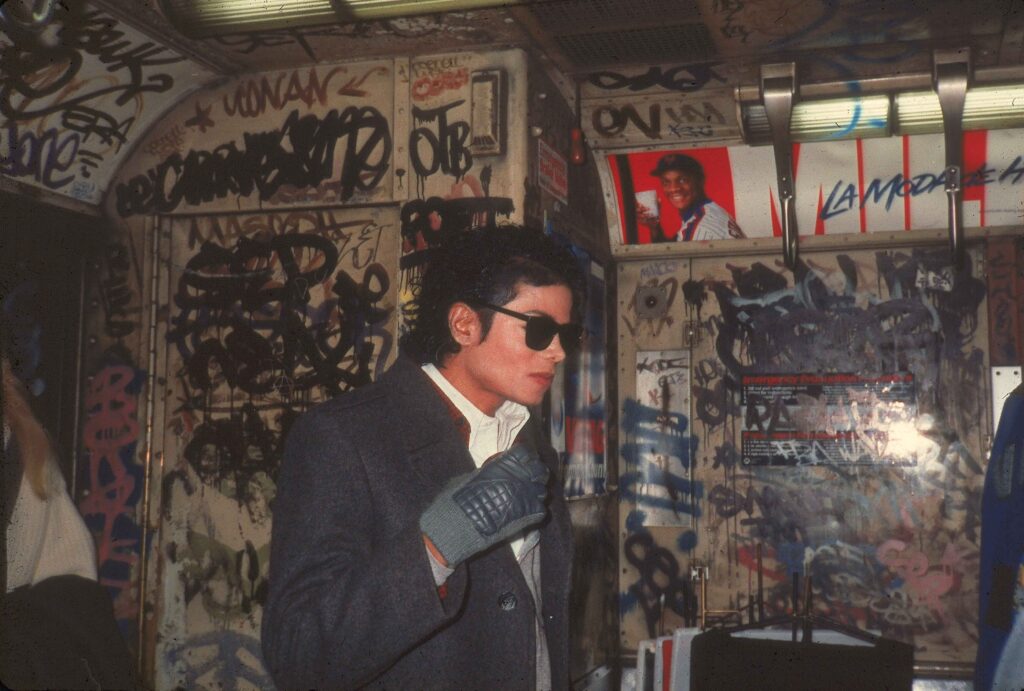

During the 1980s, graffiti became closely tied to the musical genres hip-hop and rap. Even R&B/Pop singer Michael Jackson filmed graffitied subway scenes for his 1986 “Bad” music video (directed by Martin Scorsese).

Photo by Vinnie Zuffante/Getty Images

Philadelphia considered multiple solutions to the “graffiti problem,” like cleaning or repainting surfaces along with purchasing graffiti-resistant subway cars and buses.

However, the most effective initiatives to curb graffiti were community-led art programs established between 1984 and 1986 that united art teachers, former graffiti writers and artists, and community members in the creation of public murals: the Anti-Graffiti Network, Mural Arts Philadelphia, and the Village of Arts and Humanities.

Today, Philadelphia still has graffiti, including legal sites like Graffiti Park (a former coal loading dock for the Reading Railroad known as Pier 18), but also over 4,500 murals, making it the “mural capital of the world.”

Learn More:

Bloch, Stefano. Going All City: Struggle and Survival in LA’s Graffiti Subculture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Campisi, Gloria. “Confessions of an Ex-Graffiti Addict: ‘Cornbread’ Wants a Job–Like Painting Walls.” Philadelphia Daily News (Jul. 20, 1971): 3, Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/article/philadelphia-daily-news/43811031/

Chronopoulos, Themis. Spatial Regulation in New York City: From Urban Renewal to Zero Tolerance. New York: Taylor & Francis Group, 2011.

Golden, Jane, David M. Scobey, Robin Rice, Monica Yant Kinney. Philadelphia Murals and the Stories They Tell. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2002.

Hess, Mickey. Hip Hop in America: A Regional Guide. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio, 2009.

Ley, David and Roman Cybriwsky. “Urban Graffiti as Territorial Markers.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 64.4 (Dec. 1974): 491-505, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1974.tb00998.x

Padwe, Sandy. “The Aerosol Autographers: Why They Do It.” Philadelphia Inquirer (May 2, 1971): 346, Newspapers.com, https://www.newspapers.com/article/the-philadelphia-inquirer/43810305/.

Reiss, Jon, dir. Bomb It. A Flying Cow/Antidote Films, Inc., 2007.