Photo by Afro Newspaper/Gado/Getty Images

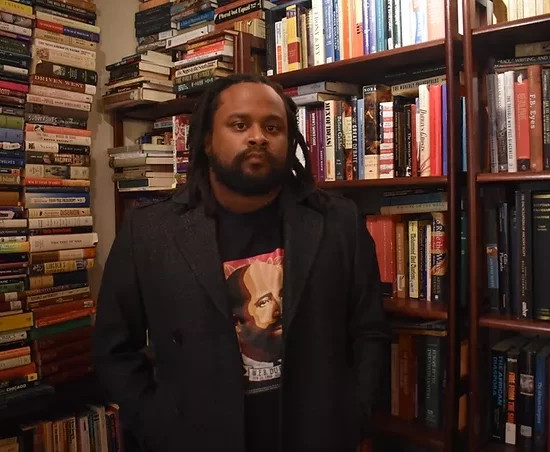

The year is 1984. Jesse Jackson is running for president in the Democratic primary. It is easy to conclude that this image is merely another example of a politician taking advantage of a photo opportunity, an orchestrated projection of the idea that politicians represent the marginalized.

But this is Jesse Jackson, so there is more in this photo than immediately meets the eye.

Jesse Jackson was not a politician. Though many political analysts called him inexperienced, he seemed personally to attract the very constituencies his campaign sought to reach.

In his own imagination, and in the imagination of many Black working-class people, Jackson had always been their advocate. A former football star, the Greenville, South Carolina native was a veteran of the Southern Black freedom struggle. He had been a staffer for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and director of its Operation Breadbasket.

An initiative of Martin Luther King, Jr., Operation Breadbasket, based in Chicago, aimed to ensure that corporations that directly benefited from their business operations in Black communities reinvested in those communities.

Under Jackson’s leadership, Operation Breadbasket led successful boycotts of large corporations unwilling to accede to its demands and executed what they called “covenants” where businesses like A&P Grocery agreed to hire and train Black employees for managerial positions, stock Black-created consumer items, utilize Black-owned service agencies, and to invest funds in Black-owned banks.

After he ran afoul of the SCLC’s leadership in the wake of King’s assassination—a controversy that haunted his efforts—Jackson branched out on his own by developing Operation PUSH (People United to Save Humanity, later changed to “Serve”).

Often appearing in a dashiki, leather jacket, Afro, and medallion of King’s likeness, Jackson frequently invoked the slogan “It’s nation time!” made famous by his comrade, Amiri Baraka. Appearing at the legendary Wattstax concert in 1972, he roused the crowd with his now famous cry of “I am somebody!”

These experiences attracted movement folk to the presidential campaign. Organizers like Ron Walters and Jack O’Dell were critical members of the campaign team. Ardent supporters Baraka and Frances Beale, as well as Black churches and social organizations, backed Jackson.

Jackson’s personal sensibilities often rankled Chicago’s machine politicians, the media, and other civil rights activists, but among the Black masses his message resonated. Together with progressive whites, college students, farmers, and Arab Americans, they were a composite portrait of those who had been effectively “locked out.”

With the exception of white feminists, most of the traditional segments of “captured” Democratic voters were moving closer and closer to the Jackson column. The old deals made behind closed doors among establishment figures were now being called into question, if not dismissed.

The foundation of Jackson’s campaign was radical and leftist, part of a long-used strategy of “Black presidential politics.” Jackson’s campaign drew from the 1972 National Black Political Convention in Gary, Indiana, which rejected mainstream liberalism and Democratic Party politics in favor of radical redistributive economic policies, reparative justice, anticolonialism, and elements of the radical welfare movement. Black women’s political struggles around sexual exploitation and labor joined this broad array of concerns.

Thus, by the time of the founding of the National Black Independent Political Party in 1980, there was a concerted effort to address issues facing Black men and women—the whole of the Black community—within a radical political movement.

So, this photograph is indeed representative. It is a depiction of Jackson and his team engaging with a Black mother and her children in the inner city. We do not know the details of their financial circumstances, but we do know that in general, Black women faced almost impossible odds as workers, as mothers, and as citizens, during the Reagan era.

Particularly, city centers enfeebled by economic neglect, the withdrawal of resources, and deep poverty were the order of the day in Black communities across the country. The Jackson campaign directly addressed these folk. It directly focused on the nature of the system that could produce such suffering, exposing how the plight of urban Black people was minimized by the Democratic Party and pathologized by the conservative movement.

Jackson lost the primary in 1984 and again in 1988. Yet the lesson here is not about electoral victory. It is about what kind of movements—rather than political campaigns—can be sustained by taking seriously the plight of people like the women and children in this photo, the lives of the locked out.

Learn more:

Frances Beale, “U.S. Politics Will Never Be The Same,” The Black Scholar 15 (September/October 1985): 10-18.

James Early, “Rainbow Politics: From Civil Rights to Civil Equality: An Interview with Jack O’Dell,” The Black Scholar 15 (September/October 1984): 50-56.

Lucius J. Barker and Ronald W. Walters, eds. Jesse Jackson’s 1984 Presidential Campaign: Challenge and Change in American Politics. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1989.

Robert C. Smith and Joseph P. McCormick II, “The Challenge of a Black Presidential Candidacy (1984): The Question of Political Independence,” New Directions 12 (July 1985): 22-25.

Lorenzo Morris, ed., The Social and Political Implications of the 1984 Jesse Jackson Presidential Campaign (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1990)