Photo by Archive Photos/Stringer/Getty Images

There is a monument that has never been erected, but it nonetheless looms tall over the settler colony of the United States. This monument does not exist in a park or a public square, in a plaza or a mall. And this monument has yet to be toppled because it exists as an ongoing list of grievances, abuses, and violence. But in the United States, perhaps we do not see this actual monument, not the one made from granite, but the one made of slavery, lynching, riots, and massacres.

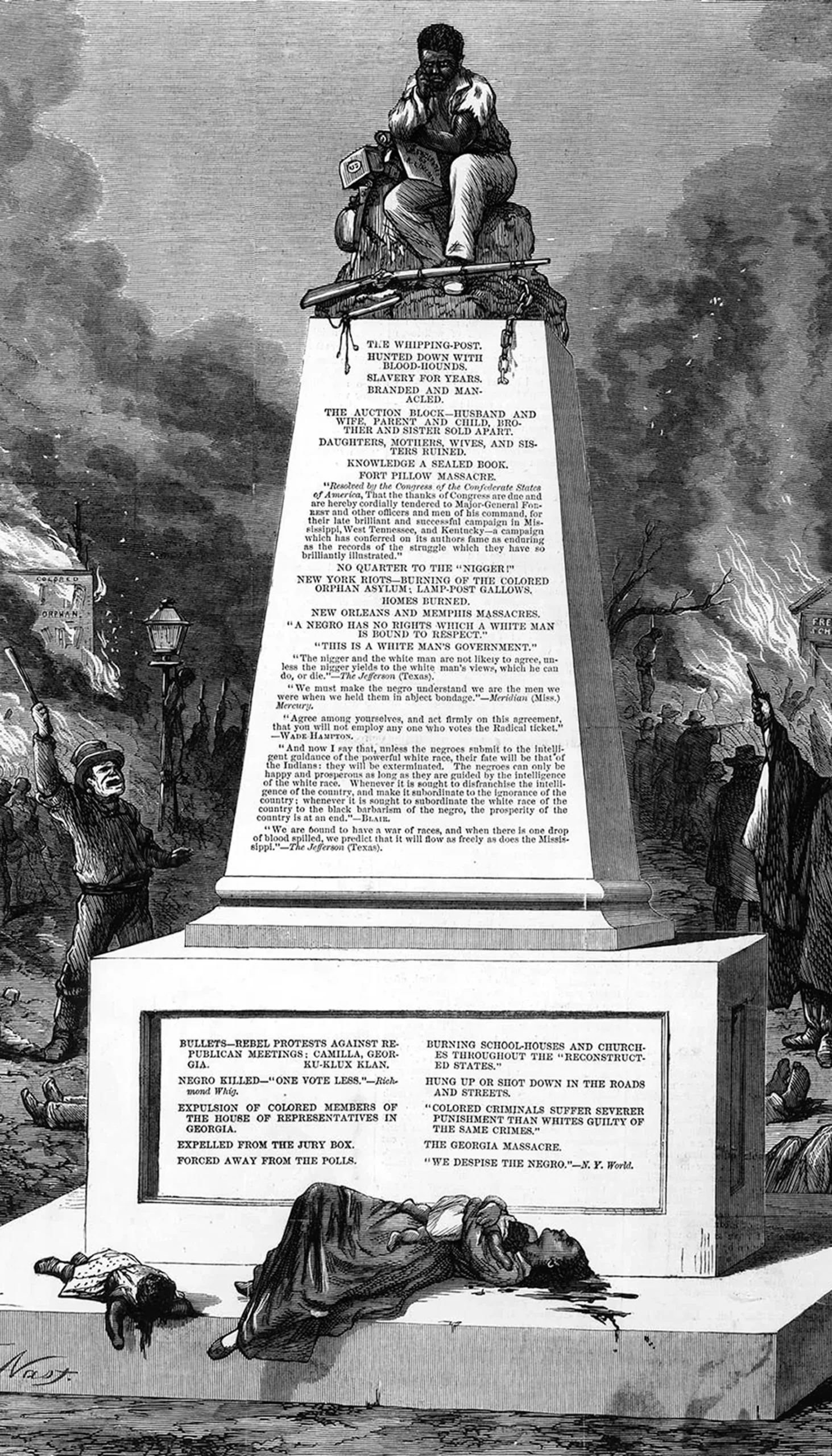

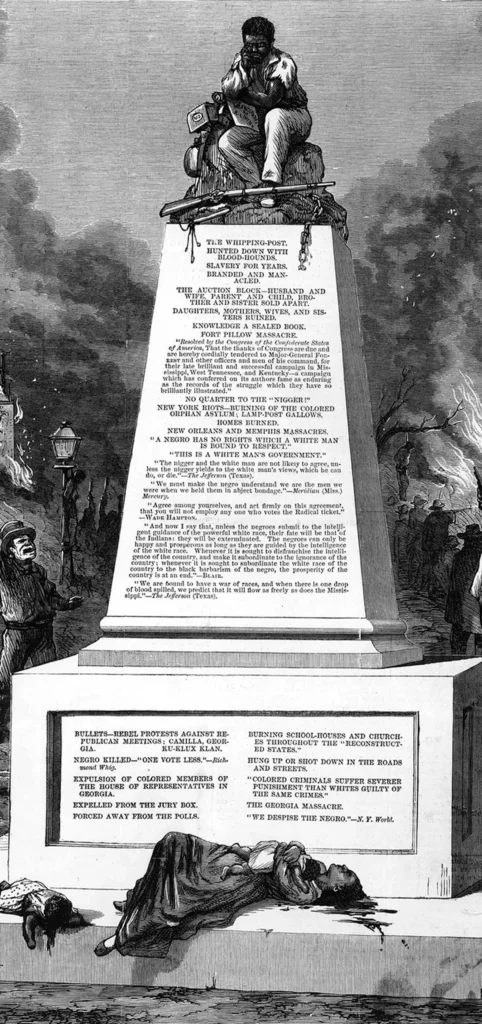

In October 1868, the skilled political cartoonist Thomas Nast gave this monument visual form when he drew “Patience on a Monument” for the Cincinnati Gazette and Harper’s Weekly. In picturing Blackness in the United States (the stories of struggle) we are also picturing Whiteness (the stories of oppression), and that oppression creates the narratives of struggle that are so compelling.

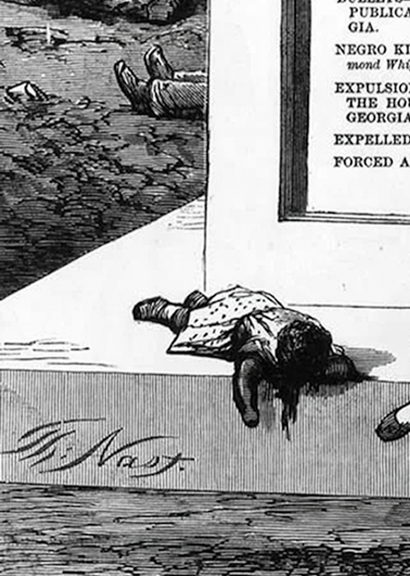

Depicting the already long and deep wounds of post-Civil War Black suffering and in the midst of the mounting failures of President Andrew Johnson during Reconstruction to safeguard African American life, Nast’s cartoon showed us a weeping Black man, likely a Union veteran with a rifle laid to rest after service to country, on top of this monument. At its base, a dead Black woman clutching her baby lies next to a dead child.

Just above those three, the monument lists historical incidents that occurred as recently as September 1868, a month before this was published, and atop that litany a set of notable quotes from historical figures.

In background we see a crowd of white citizens holding torches yelling into the night after lighting an orphanage and school ablaze. In the distance, another Black man hangs from a lynch tree, while another is bound to a light post, and yet one more is shot while he is burned by the fire. At the feet of the white crowd on the left and right of the monument are trampled bodies of Black boys and girls.

Nast’s own anger at the condonations to “former” Confederates, the capitulations to the 1st rise of the Ku Klux Klan, and the repudiation of any Black restitution is palpable. The image also summons his own horror of witnessing the New York Draft Riots of 1863, as Black men were hung from street lampposts.

Rallying cries of “Remember Fort Pillow” reference the massacre of 1864, when Confederate troops under the leadership of General Nathan Bedford Forrest brutally murdered 200 Black troops of the 13th Tennessee Regiment of the Union Army in far more depraved ways than their white counterparts. Whereas 70% of the white Union soldiers survived, only 30% of the Black soldiers did, according to many accounts.

But as cries of remembering turn into whispers of forgetting, the figure on the top of the monument still patiently waits for justice including for the New Orleans and Memphis Massacres of 1866, in which hundreds were wounded and property was seized, alongside numerous deaths.

Probably as the illustration was being drafted, the Camilla Massacre of 1868 (also known as the Georgia Massacre) occurred. It involved a 25-mile march to protest the illegal expulsion of 28 newly elected Black members of the Georgia legislature and ended in bloodshed, in a year when 336 Black people were killed.

The engraved acknowledgments of the burning of schools and churches, the public indignities of the whipping post and the auction block, and the foreclosure of suffrage are all a part of the historical mortar that constructed this monument.

The intent was not to focus on the virtue of patience. Rather, it was to highlight the very suffering and carnage that made living on a monument a reality and the absurdity of having patience with racial violence. This absurd reality was what Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation had wrought.

But if this is really a monument of Black suffering, for whom is it a monument?

Reconstruction—the great missed opportunity for a new United States to emerge from the Civil War—instead reformed the old ways of white supremacist violence through failures, double-crosses, and counter-intentions.

Reconstruction, according to Anthony Marx, was the Reformation of “Whites…unified as a race through a return to formal and informal discrimination. Blacks thus served as a scapegoat for [w]hite unity, allowing for greater stability and reducing the impediment of regional antagonism standing in the way of further nation-state consolidation.”

As the engraved quotes on the fictional monument state, “…unless the n!**** yields…he can do, or die” and “unless the negroes submit to the intelligent guidance of the powerful White race, their fate will be that of the Indians, they will be exterminated…” This last quote goes on: “whenever it is sought to subordinate the White race of the country to the Black…the prosperity of the country is at an end.”

So, perhaps this is a monument to a bitter irony unintended by Nast. Patience here is not that of Black people sitting and weeping, anxious for another, better life. The patience is that of the White crowd, who waits for the fires of burned buildings to die out.

Nast’s monument was never built, but plenty to honor the Confederacy were and many still stand. As statues for Forrest, Johnson, and a multitude of others continue to stand today, the memories of them stand even taller, their myths ever firmer, on the solid ground of this patient history. After all, “Remember Fort Pillow” has all but been forgotten.

Learn more:

Barrett, R. (2005). “On forgetting: Thomas Nast, the middle class, and the visual culture of the Draft Riots,” Prospects, 29, 25-55. doi:10.1017/S036123330000168X

Leaming, M. J. (1864, March 8). [Mack J. Leaming’s memoir of the Fort Pillow Massacre, April 15, 1893]. The Gilder Lehrman Collection, The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, New York, NY. Retrieved from https://www.gilderlehrman.org/collection/glc0508002

Marx, A. W. (2000). Making race and nation: A Comparison of the United States, South Africa, and Brazil. Cambridge University Press.

Mbembe, A. (2015). Decolonizing knowledge and the question of the archive. In A. Okune, Africa is a country: Platform for experimental collaborative ethnography, platform for experimental collaborative ethnography. https://worldpece.org/content/mbembe-achille-2015-“decolonizing-knowledge-and-question-archive”-africa-country

Thompson, E. L. (2022). Smashing statues: The rise and fall of America’s public monuments. W. W. Norton & Company.