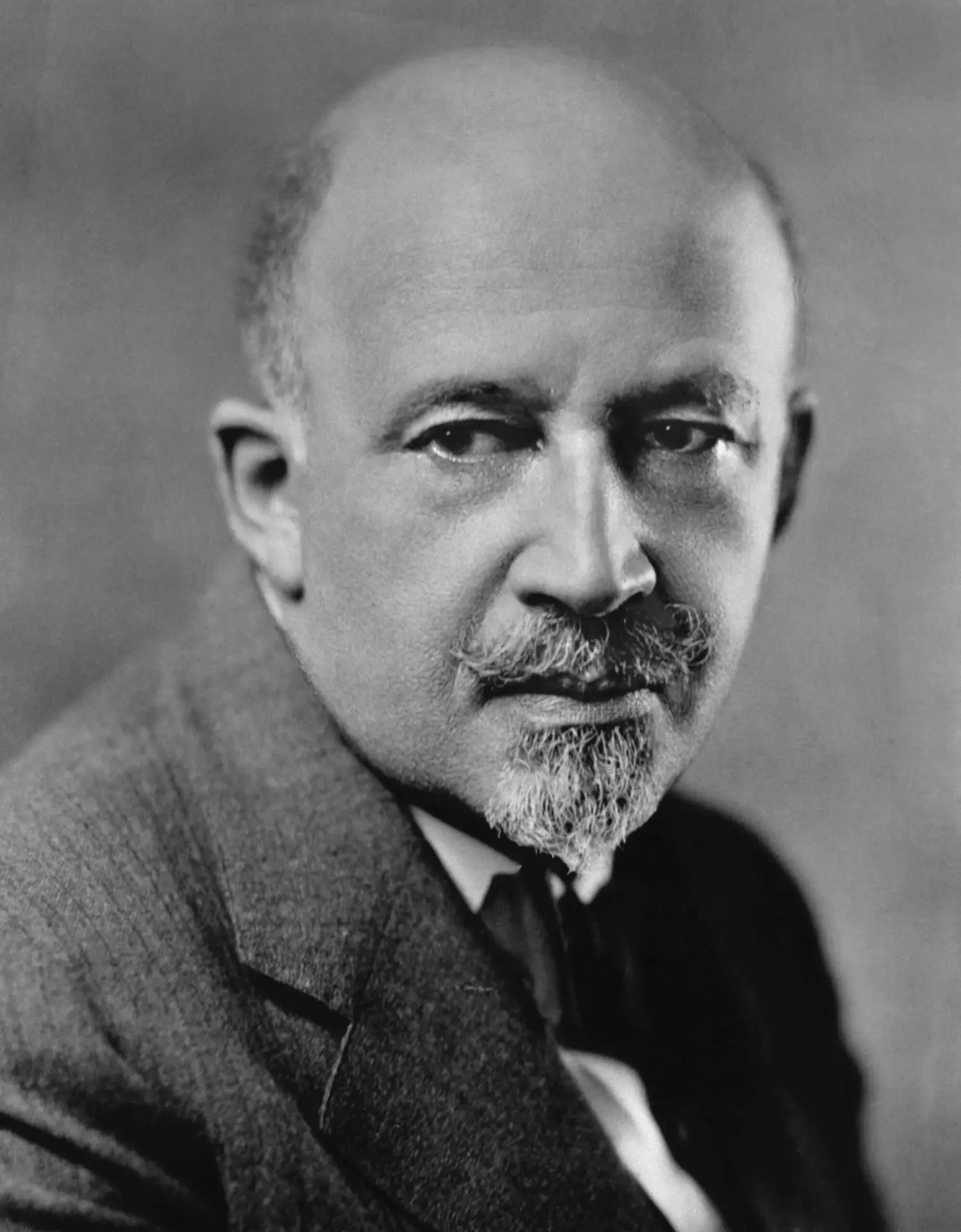

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Although he died more than 60 years ago, the life and work of W. E. B. Du Bois (1868-1963) command more attention now than ever before. Many of his concerns, in some instances over a hundred years old, remain vital issues today.

Du Bois (photographed above, c. 1920) was in the vanguard of the scholarly movement into the scientific study of social groups; he was a major voice in most of the progressive, international movements at the turn of the 20th century against imperialism and for equality more broadly. He published about two dozen books, hundreds of articles, several plays, and exquisite poetry. In all of his work, he called for a commitment to the truth as far as it could be determined, to freedom, equality, and justice for all people.

Du Bois’ formal education alone—Fisk University (he is captured as a junior at Fisk in 1887 in the colorized photo below), Harvard University, and Friedrich Wilhelms Universitӓt, the former University of Berlin—suggested the heights to which he might ascend over the course of his post-graduate life. However, his first major publication, The Philadelphia Negro (1898), launched his scholarly career.

Photo by Photo Researchers/Premium Archive/Getty Images

The University of Pennsylvania hired him to conduct a study of Philadelphia’s Seventh Ward, the city’s oldest Black neighborhood, which city leaders believed “was going to the dogs because of the crime and venality of its Negro citizens.” They expected the study to confirm that sense. Instead, Du Bois saw this project as “a chance to study an historical group of Black folk and to show exactly what their place was in the community.”

Throughout his life, Du Bois was confounded and frustrated that, despite the availability of new and better methods of study, “there [was] . . . much flippant criticism of scientific work” and that so many people were inclined “to sneer at the heroism of the laboratory while we cheer the swagger of the street broil.”

Recognizing the seriousness of the issues, he sought to complete a “careful and systematic study” that would “eventually lead to a systematic body of knowledge deserving the name of science.” He ultimately showed that the problems in the Seventh Ward—the so-called “Negro problems”—were “a symptom, not a cause.” From his perspective, anyone interested in solving any social problem had first to study it, and those who did not want to know the truth were simply cowards.

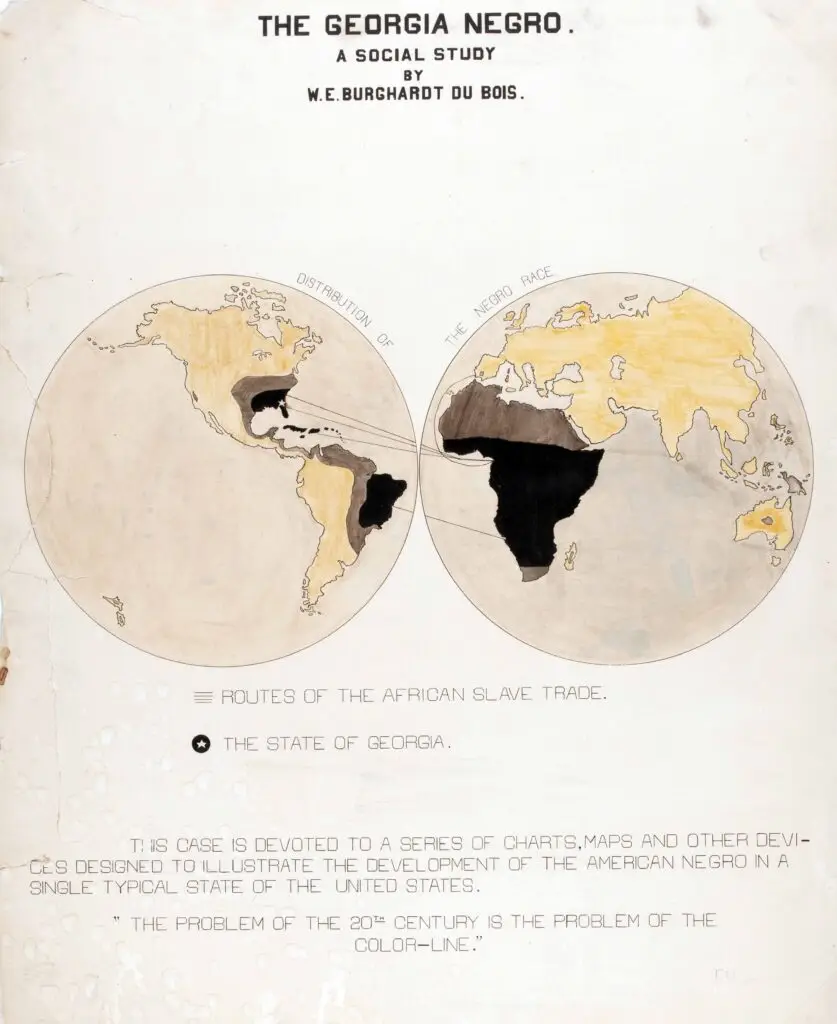

Du Bois went from Philadelphia to Atlanta University in 1897, and over the next decade he and others working under his direction completed a series of quantitative and qualitative studies that are still relied upon for details on the social, political, and economic condition of Black America at the turn of the 20th century (see details in the images below).

Photo by Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images Photo by Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

In 1899, however, the lynching of Sam Hose, a Black man who had killed his employer in an act of self-defense just southwest of Atlanta, caused Du Bois to think about abandoning social science. Before Hose could be jailed, charged, and tried, a mob tied him to a tree, tortured, and then burned him alive. Members of the mob collected body parts as souvenirs and subsequently exhibited some of them in store windows. Du Bois wondered how he could remain “a calm, cool, and detached scientist while Negros were lynched, murdered and starved.”

Fortunately, Du Bois did not actually abandon his research as the Atlanta University studies show. He produced an intensely personal study of the Black South (primarily since the Civil War Era) that began somewhat prophetically with the announcement that “The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color-line.”

The Souls of Black Folk (1903), the work for which he might be best known throughout the world, is almost a rhapsody about the poor but striving Black folk in the South, especially those in rural Tennessee with whom he lived during the summer when he taught school there (the sole three months a year that most of these children had a school available to them).

Du Bois (photographed below (at right) in the office of the NAACP’s magazine, The Crisis, ca. 1910) theorized about the role of “the Talented Tenth” (the presumed leaders of the race). Among other things, he read “the Sorrow Songs,” Black spiritual music, as America’s single, original, artistic contribution to the world. The songs were probably also a metaphor for race relations as they turned apparently discordant tones into something harmonic. While also charting the race’s progress, outlining its aspirations, and lauding and sometimes lamenting its leadership, the book was a humane and empathetic treatment of people whose poverty became proof of their inferiority for the pseudo-scientists.

Photo by George Rinhart/Corbis Historical/Getty Images

Du Bois’ most direct statement about what a country loses when it writes off so significant a segment of its population came in the form of his 1935 book, Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880, a history of Black labor during and immediately after the Civil War, the democratic movement of Reconstruction, its collapse, and the consequences of this failure.

After Black men gained the vote and began to participate in state constitutional conventions, they helped to create the most democratic state constitutions the country had ever seen. They created a public school system funded by tax dollars, ended debtors’ prisons and property requirements for voting, began seating representative juries, and reversed numerous other anti-democratic principles of the South and the country.

The book critiqued the dictatorship or oligarchy (Du Bois’ words) of the planter class, the dictatorship (and greed) of the corporate class, and perhaps most especially the failure of the white working class to recognize the common interests they had with Black southerners (photographed below in 1938 Mississippi). Sadly, poor and working-class whites, who benefitted as much as Black people did from those new constitutions, instead pinned their hopes for their future on the “white wage”—the advantage that being white, by itself, gave them, over Black people at least.

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

In recent years, efforts to keep people divided are on the rise again. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 began to reverse the damage done by ending Reconstruction (which Du Bois originally described as Black people’s effort “to reconstruct democracy in America”), but false charges of “voter fraud” endanger democracy again today. There is perhaps no bigger denial of science today than the rejection of the evidence of climate change. And the color line, so far, seems to be as much a problem of the twenty-first century as it was the twentieth.

Our failure to recognize common causes and to build on them, and deliberate efforts to keep people artificially divided, endanger us all.

Du Bois spent his whole life demonstrating that.

Learn More:

W. E. Burghart Du Bois, Dusk of Dawn: An Essay Toward an Autobiography of a Race Concept (1940; New Brunswick, 1984)

David Levering Lewis, W.E.B. Du Bois: Biography of a Race, 1868-1919 (New York, 1994)

David Levering Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois: The Fight for Equality and the American Century, 1919-1963 (New York, 2000).

Stephanie J. Shaw, W. E. B. Du Bois and The Souls of Black Folk (Chapel Hill, 2013).