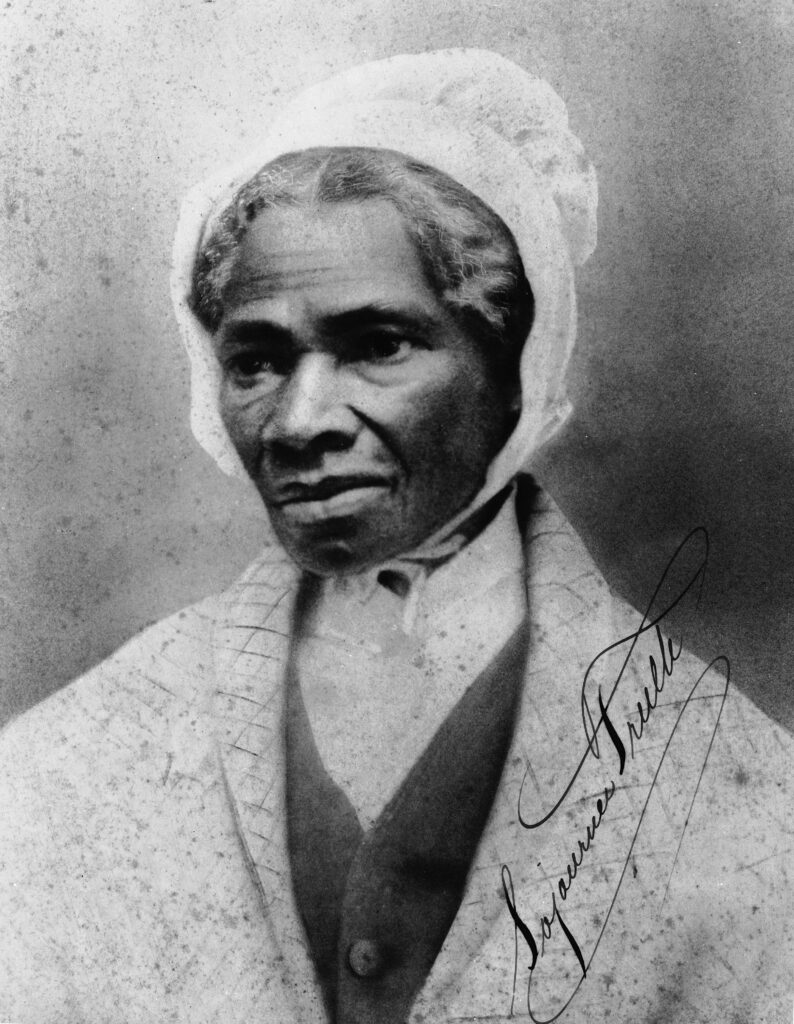

Photo by MPI/Stringer/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Sojourner Truth’s name is synonymous with her iconic speech given at the Women’s Convention in Akron, Ohio on May 29, 1851. Subsequently titled “Ain’t I a Woman,” the speech has become one of the most famous on women’s rights in American history. But it still lies between mystery, myth, and truth.

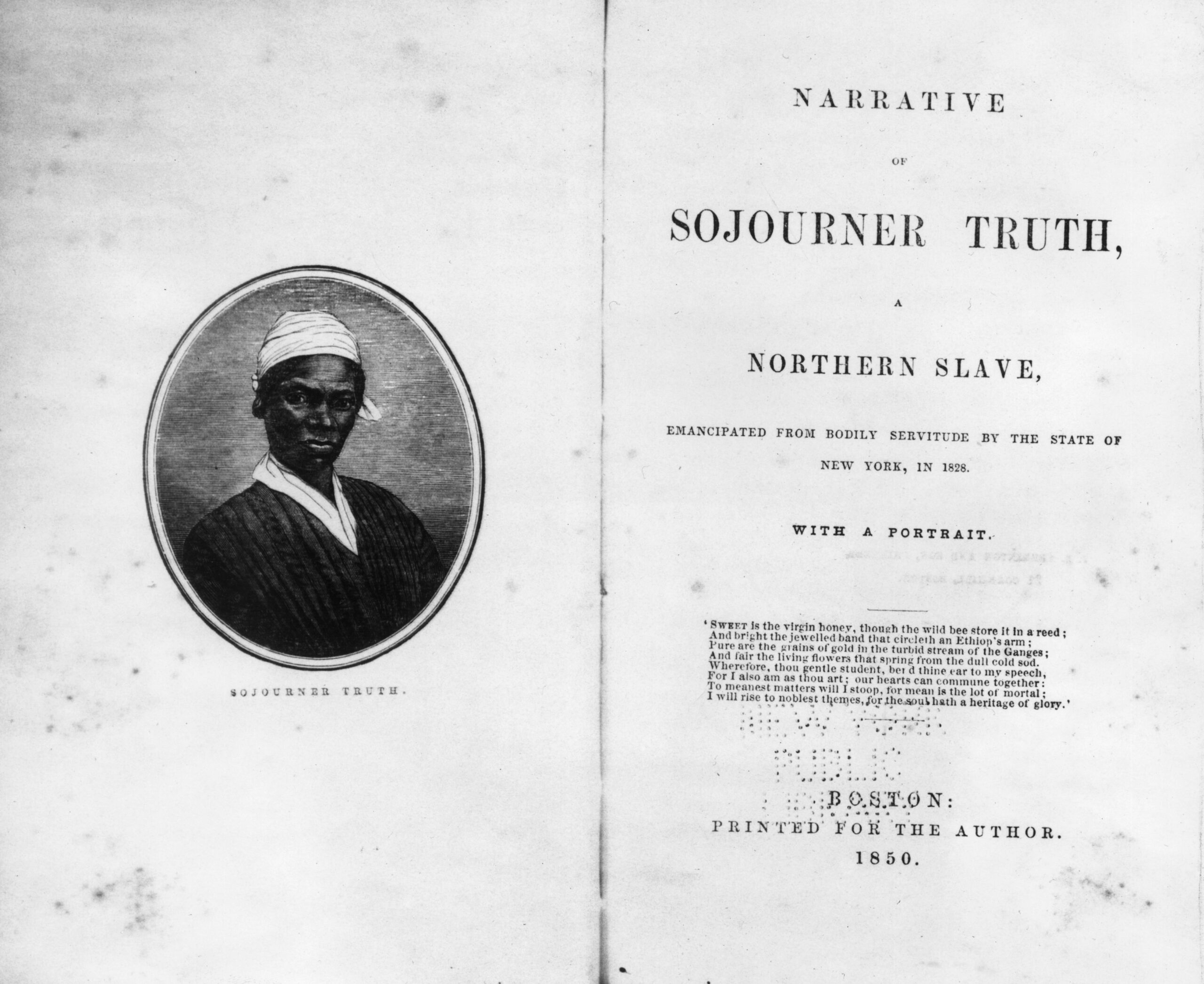

As the illustration below shows, Truth is almost always portrayed as a towering, fiery woman who spoke in a broken southern dialect, which was a common image for enslaved people. But Sojourner Truth was far from common.

Truth was born Isabella Baumfree circa 1797 in Swartekill, New York to an enslaved couple, James and Elizabeth Baumfree. Her early years were spent enslaved to Johannes Hardenberg Jr. and later to his son Charles Johannes Hardenberg. Isabella was nine years old when Charles died and she was auctioned off to John Neely, a storekeeper living in the area.

A woman of deep faith, Isabella grew up speaking Dutch. Neely beat her almost daily because she spoke no English, and young Isabella learned English to stop the violence. She became a spellbinding singer and had a gift for empowering others with words, although people noted throughout her life that she spoke with a distinct low-Dutch accent.

Isabella was only two years old when the state of New York passed a gradual emancipation law that emancipated children of enslaved mothers born after July 1799. The 1799 law would have excluded Isabella from gaining her freedom if not for another law passed in 1817 that emancipated all enslaved persons living in New York on July 4, 1827.

Isabella was sold several more times before she claimed her freedom. John Dumont, another one of Isabella’s enslavers, had promised to free Isabella in 1826, a year before the state manumission act, in recognition of her loyal service. However, he reneged on his promise claiming that an injury to her hand decreased her productivity.

Angered by this, Isabella took her daughter one morning, late in 1826, and walked away. She took refuge in the home of a nearby Dutch family, the Van Wageners. The Van Wageners did not support slavery, and when Dumont came to their home and demanded Isabella’s return, they paid him $20 for the remainder of her term of servitude and an additional $5 for her daughter.

While enslaved, Isabella had given birth to five children. Finally free, she set out to find them. Most would have received their freedom by 1827 under New York law. However, one of her children, a son, had been sold south to Alabama.

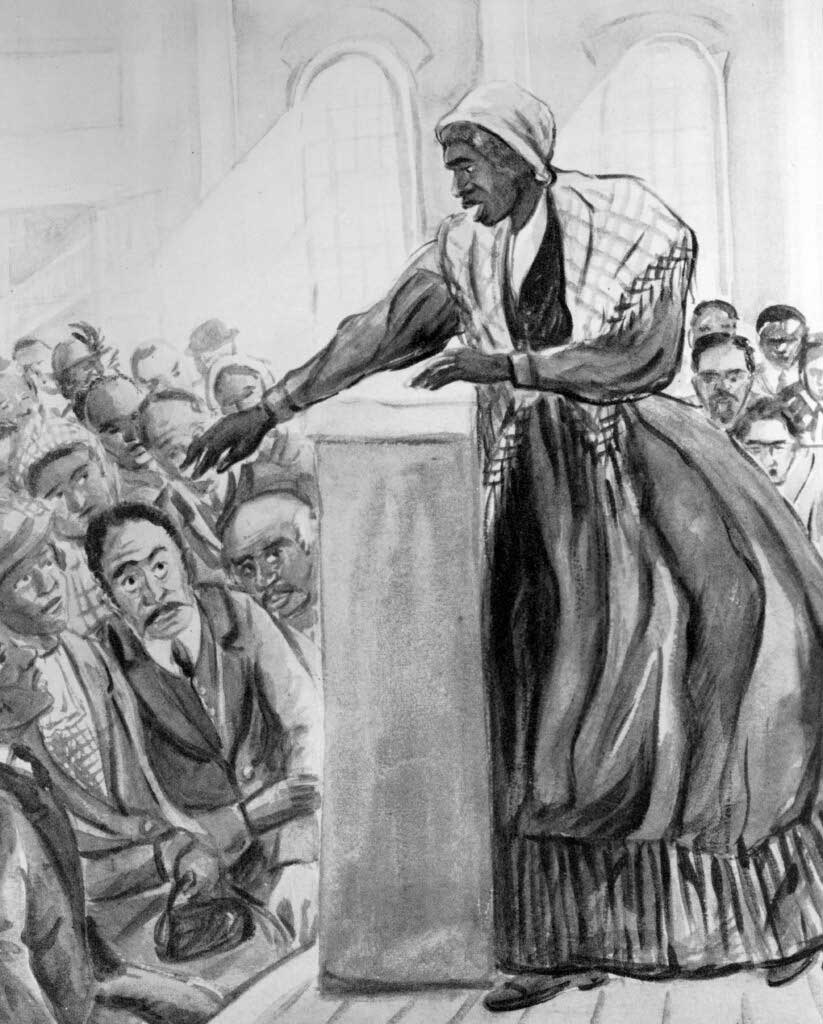

Since New York had passed a law in 1819 prohibiting the transport of enslaved people across state borders, Isabella filed a suit and managed to have the court order the return of her son, an action unprecedented at the time and depicted in her narrative pictured below.

Now calling herself Sojourner Truth, she recounted what she felt reclaiming her son: “[I]…felt so tall within – I felt as if the power of a nation was with me!”

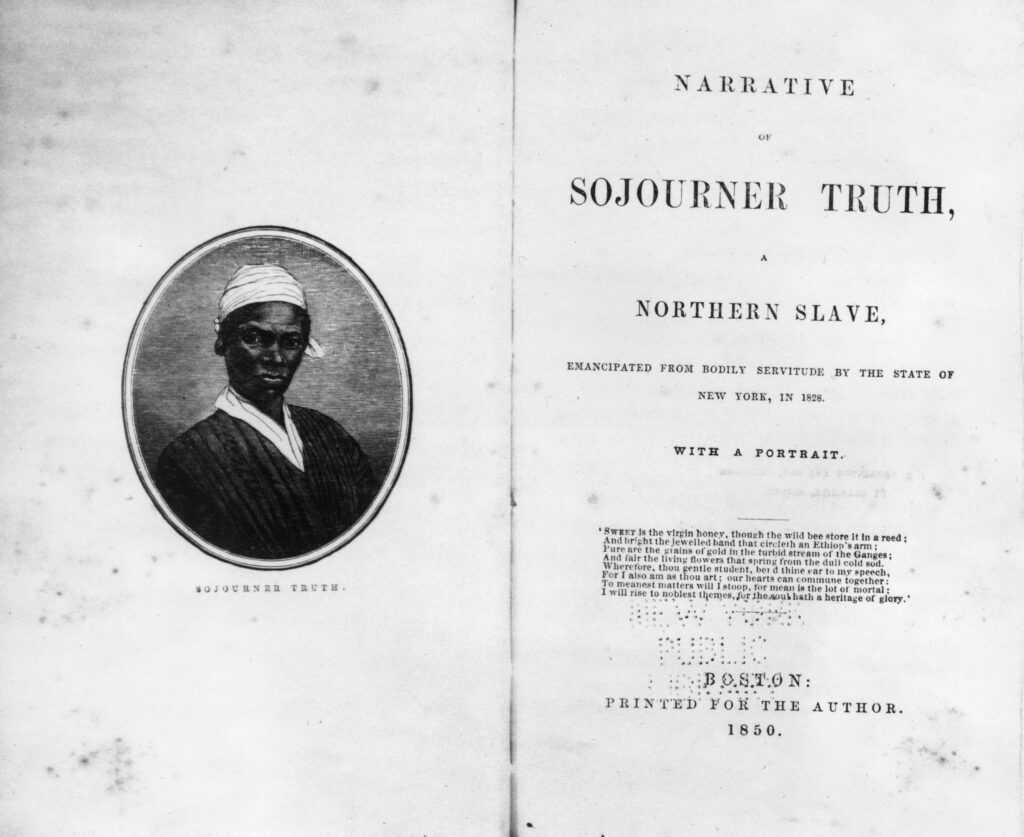

True to her name, Sojourner journeyed far and became an outspoken advocate for freedom and women’s rights for thirty years. She took ownership of her image, selling cartes de visite (calling cards or small photographs like the portrait below) bearing the phrase “I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance” to support her advocacy work (see her portrait from the 1860s below).

Nevertheless, her famous speech in Akron would be molded to fit an imagined version of the woman that others wanted her to be. Marcus Robinson published the first version of the speech a month after Truth delivered it, but the most well-known edition was published on April 23, 1863, by Frances Gage. It reads differently from the first version.

Photo by Hulton Archive/Staff/Getty Images

Many historians today embrace the idea that Robinson’s version of the speech is closer to the exact words she spoke that day in May 1851. Robinson was a personal friend of Sojourner and her host in Akron. In all likelihood, he confirmed his transcription of her speech with her before publication. He also served as the secretary for the conference and transcribed many of its other speeches.

Robinson’s version excluded dialect and emphasized Truth’s characteristic elegance and wit. In his edition of the speech, Truth never once voices the refrain, “Ain’t I a Woman.”

Frances Gage’s version, however, falsely emphasized the image of a southern Black enslaved woman almost hurling thunderbolts with her speech. It was Gage’s version where the iconic phrase, “Ain’t I a Woman” featured repeatedly, giving the speech its name.

That version of the speech, complete with Southern-sounding dialect, shaped her identity as a Southern enslaved woman and obscured her real personhood.

In reality, because slavery was almost everywhere in the United States at one point in the nation’s history, enslaved people had many regional identities and experiences. It is astonishing that much of what is widely embraced about Sojourner Truth is a myth, while the truth lives in the shadows.

Learn More:

Sojourner Truth, Narrative of Sojourner Truth

Nell Irvin Painter, Sojourner Truth: A Life, A Symbol (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1997).

Deborah Gray White, Ar’n’t I a Woman?: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1999).