Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

On February 1, 1960, four Black college students from North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College, Joseph McNeil, David Richmond, Franklin McCain, and Izell Blair, challenged racial discrimination at a lunch counter in Greensboro. After McNeil was refused service following an attempt to buy a hotdog in January 1960 at the Greensboro Greyhound Station, the four college students decided to take a stand against racial discrimination.

McNeil’s Greyhound experience reflected the system of segregation that permeated the American South and denied African Americans their basic rights. Black people could work in restaurants or spend money in stores but could not be served in those restaurants or use restrooms set aside for white patrons. After some discussion, the Greensboro Four decided to stage a sit-in at a local F. W. Woolworth store that allowed Black patrons to buy merchandise but barred them from sitting in the dining area.

Once they took their seats at the “whites only” counter, the four college students politely refused to move until the store closed for the evening. They were joined by roughly twenty of their fellow students the next day, sparking what we now know as the sit-in movement.

This action generated a huge degree of publicity and public support. It galvanized student activists across the nation, forced the desegregation of two corporate giants, and marked a pivotal moment in the development of the larger Civil Rights Movement.

By the end of the week, students from Black colleges in nearby cities such as Durham and Charlotte ignited sit-in protests at their local lunch counters. Within two months of the original sit-in, protests had spread to more than 31 southern cities in eight states.

Above is an image of students from Saint Augustine College studying at a lunch counter reserved for white customers in Raleigh nine days after the first protest in Greensboro.

The looks on the waitresses’ faces illustrate that even when Black college students were not confronted with physical violence, their protests could spark disdain and contempt from white people. While some white college students joined the protests, reactions amongst most local white people ranged from ambivalence to outright violence. However, despite this opposition, support for the sit-in movement continued to grow.

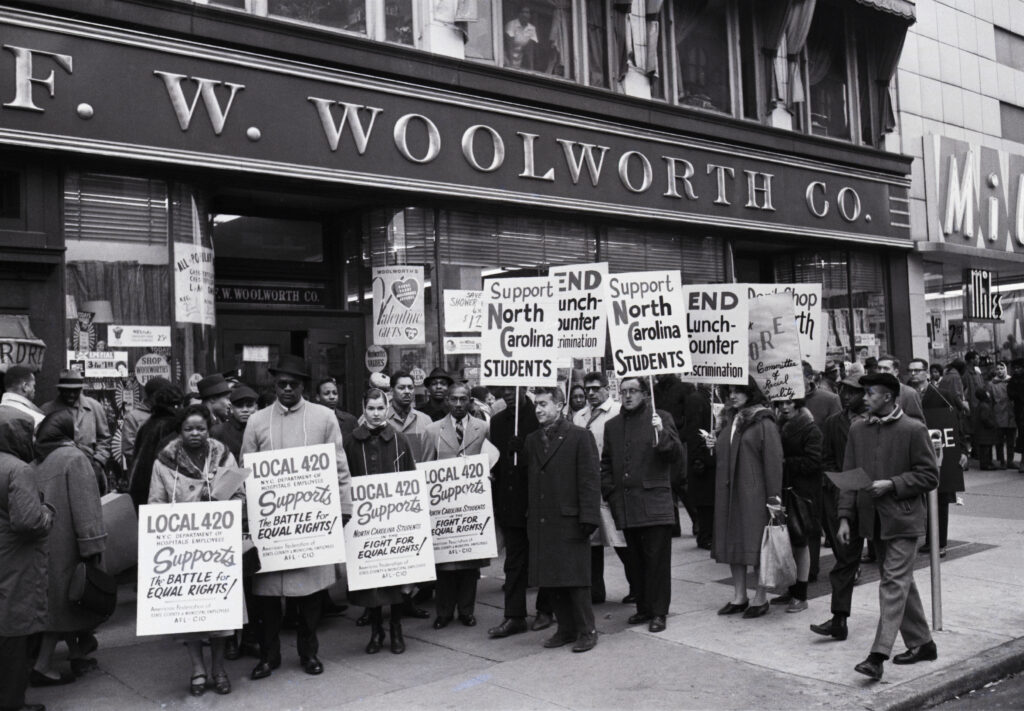

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

The photograph above, captured in mid-February 1960, less than a month after the first Greensboro protest, shows an interracial group of picketers outside a Woolworth storefront in New York City. Their placards broadcast their support for North Carolina students, and they urged Harlem residents not to patronize Woolworth stores until the company ended its discriminatory policies in its establishments in Greensboro, Durham, and Charlotte, North Carolina.

This protest exemplifies the speed at which sit-in protests swept the nation. In the image below, two members of the NAACP’s Youth Council picket near a shopping center in Fort Wayne, Indiana, in support of the student sit-in movement. One of their signs suggests a boycott of the S.S. Kresge Corporation, now known as K-Mart.

Lunch counter discrimination was not restricted to large companies. However, unlike mom-and-pop establishments, the structure of national chains like Woolworth and Kresge made them much more vulnerable to boycotts. For national corporations, the potential loss of revenue and, most importantly, reputation was a major threat. Being seen as supporting segregation was bad for business. Student activists capitalized on this vulnerability to desegregate lunch counters nationwide.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

By July 1960, Woolworth’s and S.S. Kresge had desegregated their stores in Greensboro. Other businesses in the south began to follow suit.

The growing student movement central to the sit-ins sought to co-ordinate organizing strategies on a national scale. With the help of Ella Baker, the executive director of Martin Luther King Jr.’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), student leaders maximized the momentum garnered by the sit-in movement and founded the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) in April 1960 in Raleigh, North Carolina.

The four college students who initiated the sit-in movement ultimately shaped the trajectory of desegregation efforts across the country. Their actions led to a wave of student activism that ensured the success of the Civil Rights Movement. Their example reminds us that the fight for equal rights was driven as much by the agency of everyday people as it was by leaders such as Martin Luther King, Jr.

Learn More:

Morgan, Iwan W. and Phillip Davies. From Sit-Ins to SNCC: The Student Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 2012.

Holt, Thomas C. The Movement: The African American Struggle for Civil Rights. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021.

Marable, Manning. Race, Reform and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America, 1945-1982. London: MacMillan Press, 1984.

“Two Stores Integrate Counters: Equal Service Starts Quietly.” Greensboro Daily News, Tuesday, July 26th, 1960, https://www.newspapers.com/image/939572394

King, Brayden. “Why Boycotts Succeed-and Fail.” Kellogg Insight, May 10, 2019. https://insight.kellogg.northwestern.edu/article/why_boycotts_succeed_and_fail