Photo By Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

By the mid-1980s, South African apartheid was one of the most notorious human rights issues in the world. Images of South African police attacking protesters were on the evening news. Nelson Mandela, imprisoned since 1964, had gone from obscurity in the 1970s to being a symbol for political prisoners everywhere.

Conservative governments in Europe and North America maintained their ties to the South African government for economic reasons and because it was a reliable anti-communist partner in the Cold War. Because of a shared history of racialized oppression, African Americans played a key role in driving the anti-apartheid movement in the United States.

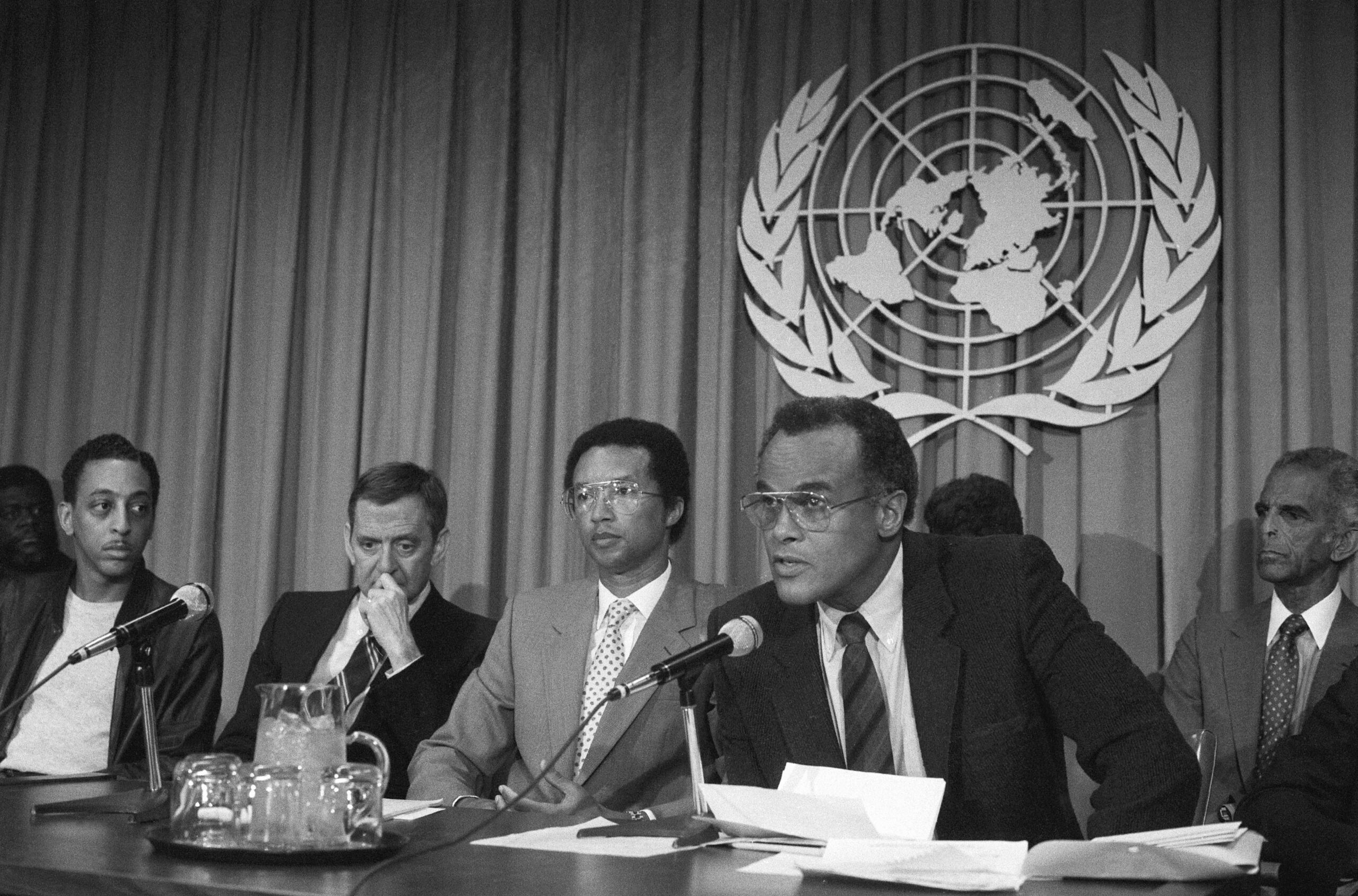

In this picture, singer and actor Harry Belafonte is speaking at a press conference at the United Nations in 1983. Accompanied by tennis player Arthur Ashe and actors Gregory Hines and Tony Randall, he was there to announce the formation of a new group, Artists and Athletes Against Apartheid.

The purpose of this new group was to call for a cultural boycott against South Africa: musicians would refuse to tour there, and actors would refuse to appear in productions there. It followed several high-profile visits from American musicians such as Frank Sinatra, who had played at South Africa’s infamous Sun City resort in 1981.

Belafonte admired Paul Robeson’s activism. As early as the 1950s, Belafonte had helped plan African Freedom Day celebrations with the American Committee on Africa. He helped raise money for activist groups and to popularize artists from South Africa.

Belafonte began collaborating with South African musician Miriam Makeba, releasing the album, An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba, in 1965. Similarly, he befriended jazz trumpeter Hugh Masekela shortly after he came to the United States.

Belafonte was not alone among musicians.

As early as 1960, Max Roach’s civil rights jazz album We Insist! included a track, “Tears for Johannesburg,” that drew parallels between the two countries and condemned the Sharpeville Massacre. It set a precedent followed by work such as Gil Scott-Heron’s From South Africa to South Carolina.

Arthur Ashe, also pictured here, was one of the faces of the sports boycott. This boycott worked to isolate South Africa, either by preventing South African teams from competing in events such as the Olympics, protesting visiting South African sports teams, or by urging American athletes to not visit. Ashe, one of the first African American tennis champions, had been denied a visa to compete in South Africa until 1973.

Photo By Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

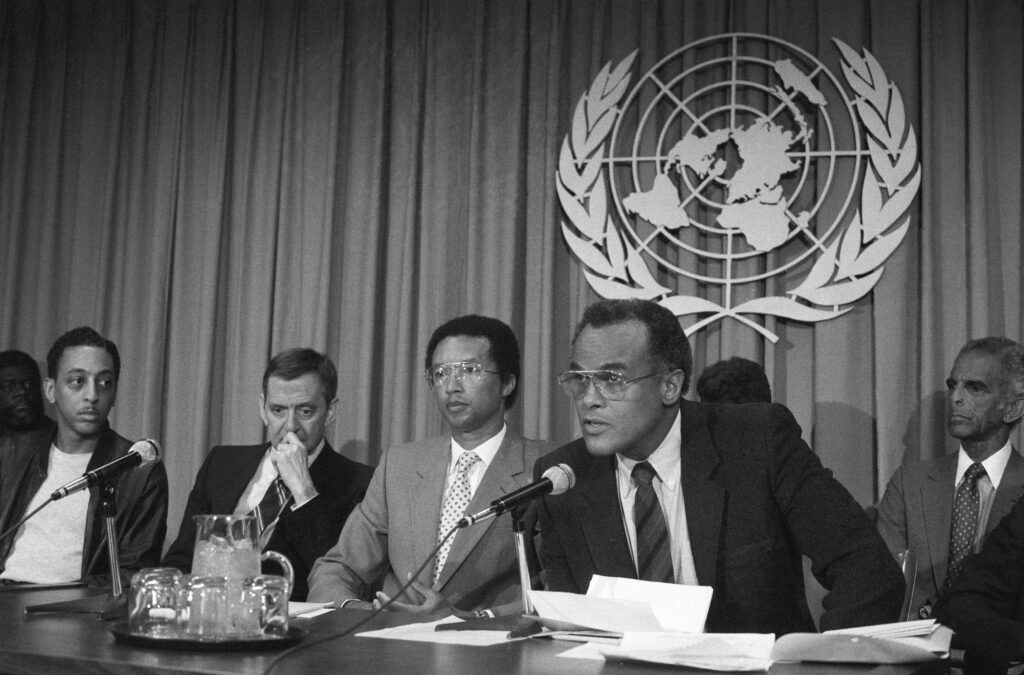

In the photograph above, Coretta Scott King, widow of the late Martin Luther King, Jr., and her children Bernice & Martin are being arrested as they protest apartheid at the South African Embassy in Washington, D.C. in 1985.

This was a pivotal moment in the anti-apartheid movement in this country. A few days before these arrests, Randall Robinson of the social justice organization TransAfrica had staged a sit-in at the same embassy along with Mary Frances Berry, Walter Fauntroy, and Eleanor Holmes Norton.

They refused to leave, demanding a release of all political prisoners in South Africa, and all three were arrested. They had timed the sit-in for the day before Thanksgiving to ensure that it happened on a slow news day, and the arrests were widely reported.

These actions set off daily protests at the South African embassy as well as at South African consulates around the United States, and TransAfrica helped to organize this into a new campaign, the Free South Africa Movement (FSAM). At a local level throughout the South, the SCLC organized boycotts of banks that sold Krugerrands, the South African currency, or grocery stores selling South African produce.

FSAM and its publicity led to a policy shift in 1986. Activists had wanted the U.S. government to pass trade sanctions and embargoes against South Africa since the early 1960s, but both Congress and the White House were unwilling to risk alienating a key U.S. ally.

By the 1980s, however, that had changed. While the Reagan Administration was made up of staunch supporters of South Africa, both Republicans and Democrats in the House and Senate faced mounting public pressure to do something. This meant rebuking the White House on a matter of foreign policy.

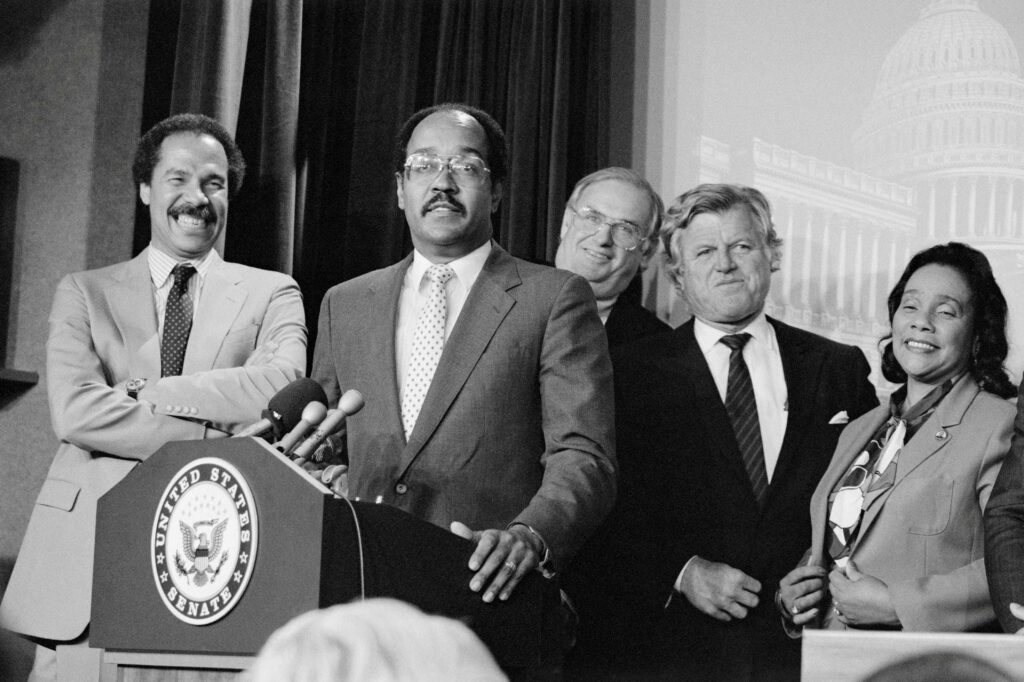

Photo By Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

Every year, the House or the Senate took up legislation targeting South Africa; Rep. Ron Dellums introduced a bill to impose full sanctions every year starting in 1972. But full sanctions had not seemed like a real possibility until 1985, when FSAM and a host of other grassroots movements had prioritized the passage of trade sanctions and begun lobbying Congress in earnest.

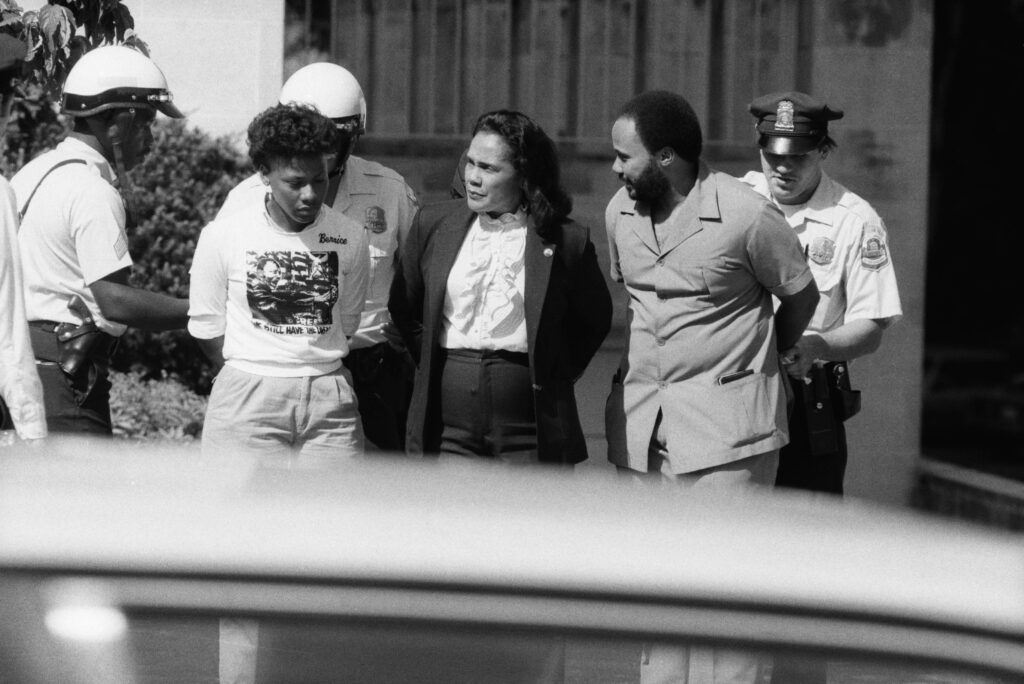

In the image above, Randall Robinson, William Howard Gray III, Lowell Weicker, Ted Kennedy, and Coretta Scott King are speaking to reporters following the Senate override of President Reagan’s veto of the Comprehensive Anti-Apartheid Act.

The Reagan Administration opposed this Act, sponsoring a set of mostly symbolic executive orders that failed to satisfy activists. Gray was one of the architects of the eventual sanctions bill. He was joined both by longtime Democratic allies such as Ted Kennedy and Republicans such as Lowell Weicker, who had by now either grown disgusted with South Africa or received too much criticism from constituents. When Reagan vetoed the bill, Republicans turned on him and overrode his veto.

Sanctions by the U.S. government were not solely responsible for ending apartheid; the Reagan Administration was lax in its enforcement of them. But it signaled the country’s isolation and further weakened its economy at a time when it could ill afford further turmoil.

Battered by unemployment, a state of emergency that made parts of the country ungovernable, and wars in Angola and Namibia, even previously staunch supporters of apartheid began to think that negotiations were preferable to the alternative.

African Americans thus played a key role in undermining one of the pillars of global white supremacy.

Learn More:

Nicholas Grant. Winning Our Freedoms Together: African Americans and Apartheid, 1945-1960.

Robert Massie. Loosing the Bonds: The United States and South Africa in the Apartheid Years.

Francis Nesbitt. Race for Sanctions: African Americans Against Apartheid, 1946-1994.