Photo by AfroNewspapers/Gado/Getty Images

In the early 20th century, Americans embraced swimming as a popular form of recreation. This trend coincided with the Great Migration, a large-scale movement of southern African Americans to northern cities in an effort to escape Jim Crow racial segregation. Many learned that northern racism was less overt but no less systemic. It ran through the deepest waters.

Photo by Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

Sugar Ray Robinson (left in the photo above) and Hal Jackson (right) became two of the most prominent Black Americans of the 1950s. A pioneer in broadcasting, Jackson’s radio programs in New York City featuring jazz music and celebrity interviews reached millions of listeners nightly. A multiple winner of the World Middleweight boxing title, Robinson remains ranked as one of the sport’s all-time greats.

In 1955, a photographer caught them relaxing on the beach in Atlantic City, New Jersey, just south of the famed Million Dollar Pier. The shore area off Missouri Avenue was the only beach Black people could visit. It came to be called “Chicken Bone Beach” after the remnants of a favorite picnic food. Fried chicken held up well in the heat and provided sustenance for Black beachgoers, who were not welcome to dine in Atlantic City’s “White Only” eateries.

At the time Robinson and Jackson were photographed on New Jersey’s designated Black beach, African Americans in Baltimore were flocking by the thousands to swim in Druid Hill Park Pool No. 2 (see photo below). It served over 100,000 Black residents, but measured only half the size of Baltimore’s Pool No. 1, reserved for whites only. Baltimore, a city on the border between the North and the South, operated seven public pools, all segregated by race.

Because Black Americans had limited opportunities to swim, they faced greater chances of drowning. Two years prior to this photograph, a Black child drowned after jumping into the Patapsco River near Baltimore’s Hanover Street Bridge. Thirteen years old, the boy lived near Clifton Park, where whites denied him and all Blacks access to the local pool. By the 1970s, only about 30% of Black Americans knew how to swim, the same as today.

As a result, the NAACP successfully sued to desegregate Baltimore’s public pools. In 1956, Baltimore officially abandoned its policy of maintaining segregated pools. White attendance in public pools dropped rapidly by 60%. Meanwhile, construction began on the Roland Park Swimming Pool, sponsored by the Roland Park Civic League. Financed by individuals, it soon opened as a private swim club, one that regulated membership by race.

What transpired in Baltimore became commonplace nationally. As African Americans gained access to public pools, whites abandoned those spaces and created others that were private and exclusive, exempt from court rulings demanding inclusivity for public places.

This private segregation of pools did not go uncontested.

With the backing of John Lewis and other members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), African Americans in Cairo, Illinois challenged their town’s segregationist status quo. This included protesting for access to the public pool. In response, local officials closed the pool and reopened it with a sign designating it as a private, whites-only swim club.

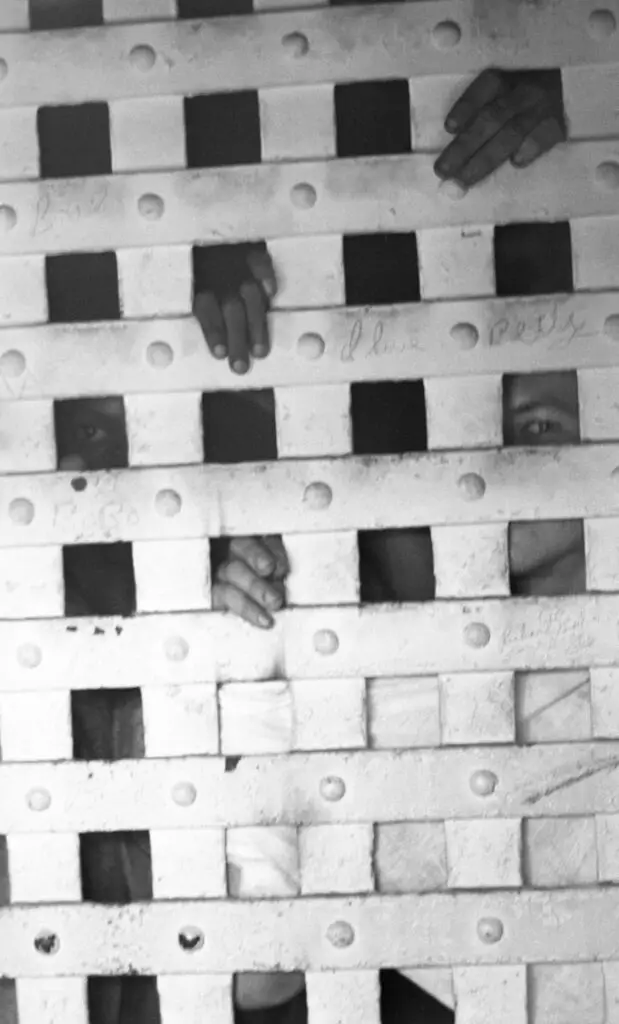

On July 13,1962, seventeen youths staged a stand-in demonstration in hopes of securing access to the pool for everybody, regardless of race. This protest ended with their arrest. The photo below depicts them jailed in the Alexander County Courthouse. Their faces are largely hidden. However, their visible hands suggest that Cairo’s officials, while opposing the idea of racially integrated swimming, embraced a different view regarding incarceration.

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

By the end of the summer, Illinois Governor Otto Kerner, Jr. ordered the city to comply with state law and desegregate all facilities. In 1963, Cairo authorities closed the pool to avoid integrating it. That same summer, Charles Bridges, a Black firefighter in Cairo, lost his older brother, who drowned trying to swim in the Ohio River.

The situation in Cairo contrasted sharply with developments shortly before then in Yeadon, Pa. Located just outside of Philadelphia, the western part of Yeadon became one of America’s first Black suburban enclaves in the 1930s. The Great Depression provided a chance for African Americans to purchase homes vacated by whites. Still, the town remained mostly white and, outside of racially integrated Yeadon High School, segregated, including the town’s swim club.

In 1957, a few Black families living in West Yeadon applied to join the private Yeadon Swim Club. Their applications were ignored. Repeated attempts to get a decision produced only frustration. The families began meeting to weigh their options.

According to her husband Robert, Zoe Mask grew impatient with what she perceived as endless discussion. “Since they evidently don’t want us at their swim club, why don’t we just build our own,” she suggested. To acknowledge the community’s African heritage, Zoe also suggested a name: “Let’s call it the Nile.”

A regional effort to fund an unprecedented, Black owned and operated swim club, was enthusiastically commenced. Hundreds of Black families from the greater Philadelphia area, accustomed to journeying to “Chicken Bone Beach,” contributed $250, the equivalent of over $2,000 today, to build the Nile Swim Club of Yeadon.

On July 11, 1959, the Nile opened to hundreds of guests. It welcomed all, regardless of race, and offered the nation a model of inclusivity. The Nile became a Black cultural hub, hailed by Ebony magazine as the epicenter of the “Black Mainline,” while playing host to notables such as Jesse Owens, Harry Belafonte, and the Supremes. Regardless of race, the Nile positioned the ability to swim as a right, not a luxury afforded by the color of one’s skin.

That remains the Nile’s mantra. Bill Mellix, present at the Nile’s opening when he was 13, recalls, “None of us knew how to swim.” For most Black Americans, sixty years later, that remains the case. The Nile works to remedy that one person at a time by providing free swimming lessons to all.

The Yeadon Swim Club, exclusive to the end, shuttered years ago.

Long live the Nile.

Learn More:

Cheryl Woodruf Brooks, Chicken Bone Beach: A Pictorial History of Atlantic City’s Missouri Avenue Beach (Mechanicsburg, PA: Sunbury Press, 2017).

Robert J. Kodosky, The Nile Swim Club of Yeadon: A History (Charleston, SC: The History Press), 2024.

Pool: A Social History of Segregation. https://fairmountwaterworks.org/pool/

Jeff Wiltse, Contested Waters: A History of Swimming Pools in America (Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009).