Photo by Charles “Teenie” Harris/Getty Images

In popular histories of jazz, New Orleans and New York dominate. While both cities are incredibly important in the development of the music, they weren’t the only places where music was being made.

Just about every city that had a large African American population had a neighborhood where people lived and in turn where music culture was made.

In Louisville, it was Walnut Street. In Memphis, it was Beale Street. Portland, Oregon had the Albina neighborhood; Milwaukee had Bronzeville; 18th and Vine was the nerve center of jazz in Kansas City; and in Pittsburgh it was the Hill District.

Some places leaned more towards jazz, such as Albina or the Hill District, while others like West Oakland or Beale Street favored the blues.

As the Great Migration, which began in the 1910s, drew Black southerners north and west in search of industrial jobs, Pittsburgh became a destination because of its large industrial base.

The new African American arrivals to the Steel City were forced to live in segregated areas like the Hill District, which also had thriving Italian and Jewish communities. The Hill District quickly became overcrowded, with some sleeping in shifts in boarding houses because of a housing shortage.

But the neighborhood was also home to social clubs that helped new arrivals get centered in Pittsburgh. It was home to the nationally circulated Pittsburgh Courier, one of the most famous African American newspapers, and the playwright August Wilson set most of his plays in the Hill District.

And, of course, there was music.

Photo by Charles “Teenie” Harris/Getty Images

Pittsburgh certainly contributed a great deal to jazz; some of the leading luminaries came from the city. Pianists Ahmad Jamal, Earl Hines, and Mary Lou Williams, drummer Art Blakey, and composer Billy Strayhorn all grew up in Pittsburgh. (Jamal is pictured above on piano in 1945 with Jon Morris on Trombone, Harold “Brushes” Lee on drums, Horace Turner on Trumpet, John Foster on saxophone, and Sam Hurt, partially cut off on the right.)

Even as early as 1920 when jazz was still very much a novelty, Hines was heading over to the Hill District and listening to what he heard in clubs so that he could create his own distinctive style.

While these more famous musicians had to leave in order to become national talents, Pittsburgh was still important for them: Jamal said that “Pittsburgh meant everything to me and it still does.” But there were also many musicians who stayed in Pittsburgh. The Hill District had its own musicians’ union, Local 471, primarily for African American members.

Photo by Charles “Teenie” Harris/Getty Images

The city, and the Hill District in particular, was also a popular destination for nationally renowned jazz musicians. Dizzy Gillespie once said, “One thing I like about playing Pittsburgh is that you’ve really got to cut it or get laughed off the stand … They all seem to know what’s happening. You don’t dare relax and hit a bad note.”

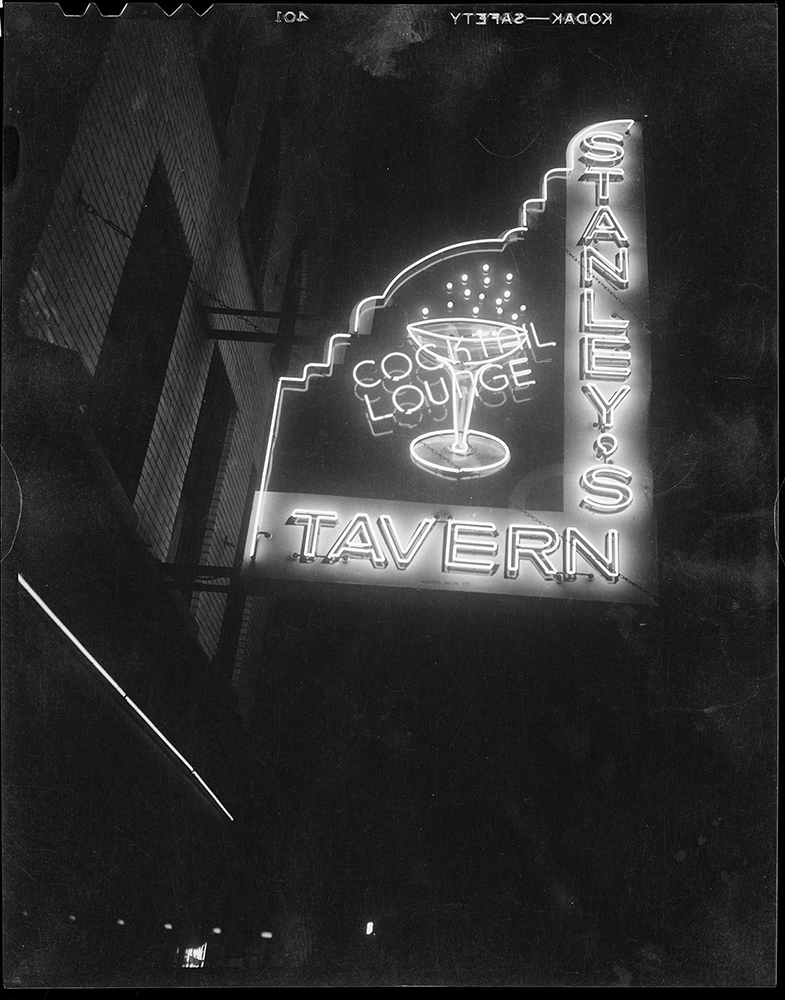

The Hill District was home to numerous music venues that became major stopovers for visiting musicians as well as regular hotspots.

The Crawford Grill, the Sawdust Trail, the Musicians’ Club, the Stanley Theater, the Lincoln Tavern, or Stanley’s Tavern (shown in the Teenie Harris photograph above) were just a few of the places where jazz could be heard nightly, where young musicians could play with veterans of the city’s music scene or with touring musicians.

Famously, Duke Ellington met Strayhorn at the Crawford Grill and then heard him play at the Stanley Theater. He invited him to work with him, and the result was a multi-decade composing partnership.

Photo by Charles “Teenie” Harris/Getty Images

What spelled the end of many of these neighborhoods, or at least severely disrupted them, was urban renewal beginning in the 1950s. This destruction and rebuilding were justified by politicians because the neighborhoods often were filled with dilapidated structures and decaying buildings. There was truth in this, but no plan was made to accommodate the people displaced by the demolition.

The Hill District exemplifies this process (pictured above on Wylie Ave in the Lower Hill District in the late 1950s). Beginning in 1955, the city government used eminent domain to displace more than 8,000 residents and 400 businesses of the Hill District. Some of the clubs such as the Crawford Grill were able to relocate and survive, but this drove a fissure through the neighborhood.

Portland’s jazz clubs were destroyed in a similar way through the construction of the I-5 corridor. Kansas City’s 18th and Vine was first targeted because of crime in the 1940s, forcing many clubs to cut costs and get rid of live music in favor of jukeboxes. Then in the 1950s, more businesses and homes were targeted for demolition, and nothing was built up to replace what had been lost.

The last blow for the Hill District came in 1968 when Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. The riots that engulfed the Hill District did a lot of physical damage to the neighborhood and forced businesses to leave. They also created a perception that the neighborhood itself was unsafe, and the remaining white residents and businesses began pulling out.

Most of the clubs went too, often because they lacked the client base to sustain themselves. A few such as the Crawford hung on, but it marked the end of an era for the Hill District.

Regional musical histories like the Hill District bring to life both culture and community. Seeing how significant musicians such as Hines or Jamal got their start and how their milieu influenced them deepens our understanding of this music.

But it also highlights how communities are built and sustained, and where we might make different choices in the future to protect those communities.

Learn More:

Robert Dietsche. Jumptown: The Golden Years of Portland Jazz, 1942-1957.

Colter Harper. Jazz in the Hill: Nightlife and Narratives of a Pittsburgh Neighborhood. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi, 2024.

Joel William Trotter, Jr. and Jared Day. Race and Renaissance: African Americans in Pittsburgh Since World War Two. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2010.