Photo by Flip Schulke Archives/Corbis Premium Historical/Getty Images

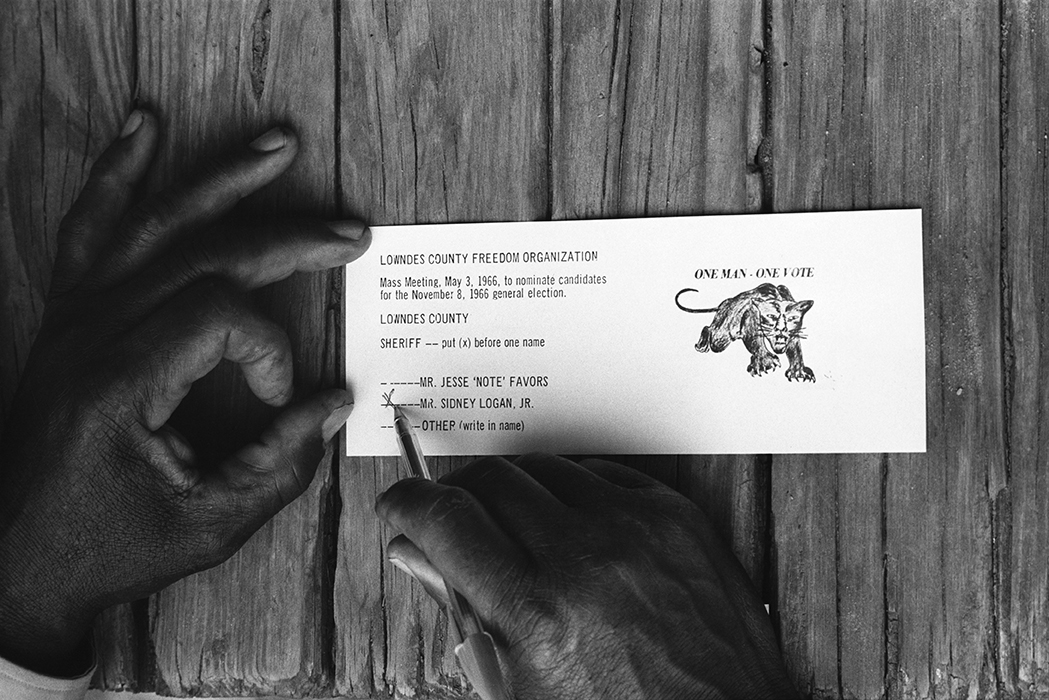

In the spring of 1960, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and Ella Baker of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) organized a youth leadership meeting at Shaw University in North Carolina. King and Baker recognized that nonviolent tactics like the lunch counter sit-in strategy prepared college students to win the battle for civil rights. They hoped to create a youth wing of the SCLC committed to nonviolent resistance (see the photograph below about the meeting).

Photo by Smith Collection/Gado/Archive Photos/Getty Images

However, shortly after the meeting convened, the students decided that the SCLC’s values did not fully align with how they saw their role in the civil rights movement. Rather than joining the SCLC, the young leaders formed a new organization, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), better to reflect their conviction that lasting change required aggressive action.

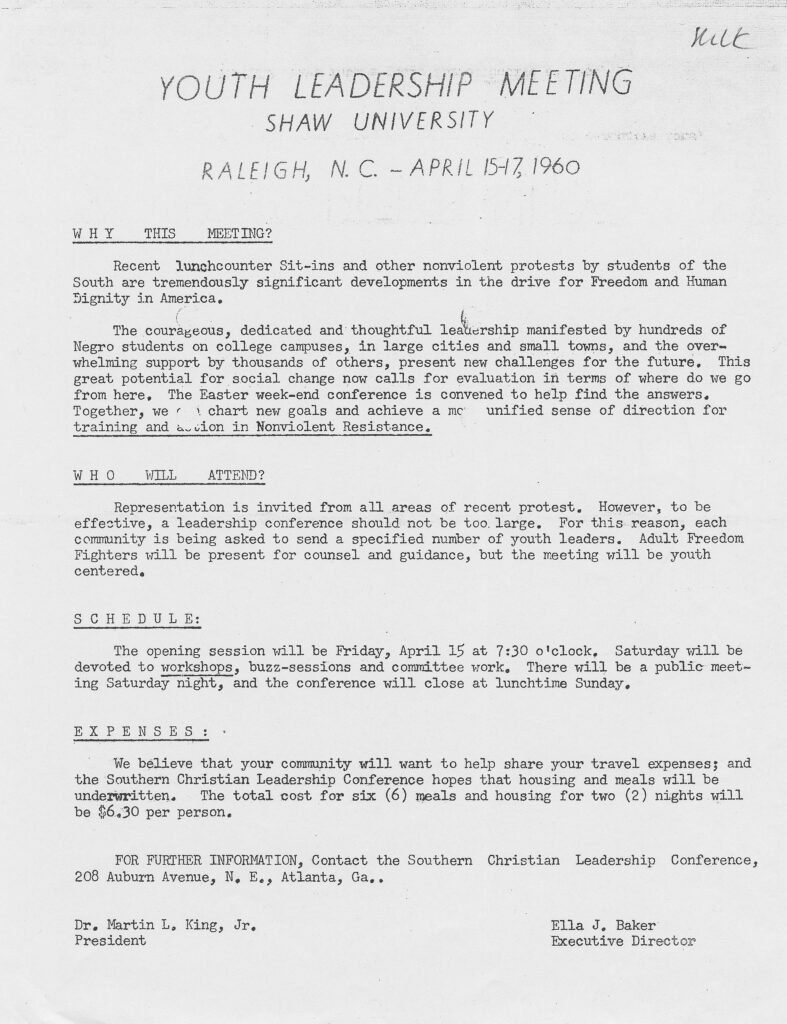

Several students who later rose to prominence in the Civil Rights Movement, including John Lewis, Diane Nash, Chuck McDew, and Julian Bond, attended the Shaw meeting. They listened to Dr. King preach that nonviolence was the only acceptable way to combat American racism, but many students at Shaw disagreed. The photo below illustrates why. When student activists sat down to order food in a “whites only” space, organized white counter-protesters responded with verbal and physical abuse.

Photo by Wally McNamee/Corbis Historical/Getty Images

As desegregation gained momentum as a political cause, white supremacists attacked its proponents by appealing to antisemitism and anti-communism because Jews and communists worked with Black Americans to advance civil rights. The men harassing the customers in the photo designed the caricatures on the posters to dehumanize protestors. In an environment like this, many of the students found nonviolence insufficient.

McDew explained SNCC’s desire to retain self-defense as an option. He recalled an event in which Gandhi stopped trains by having protestors lay on the tracks. Gandhi gambled that a train engineer’s humanity would prevent them from running over protestors. McDew believed that if you applied that same tactic in the United States, “a train would run you over and back up to make certain you’re dead.”

While the young protestors chose to remain outside SCLC, they maintained a close partnership. Shortly after the Shaw meeting, SNCC affirmed their collaborative relationship with the SCLC by agreeing to coordinate “in all possible and appropriate ways.” They also established SNCC’s headquarters in the SCLC’s Atlanta offices and listed King as an advisor.

While SNCC realized that legitimacy came through aligning with the SCLC, the group also realized that there was an ideological divide between themselves and established freedom fighters like King.

Nevertheless, as SNCC matured, so too did its tactical strategy. Throughout the early 1960s, its members wrestled with the merits of nonviolence versus armed self-defense.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

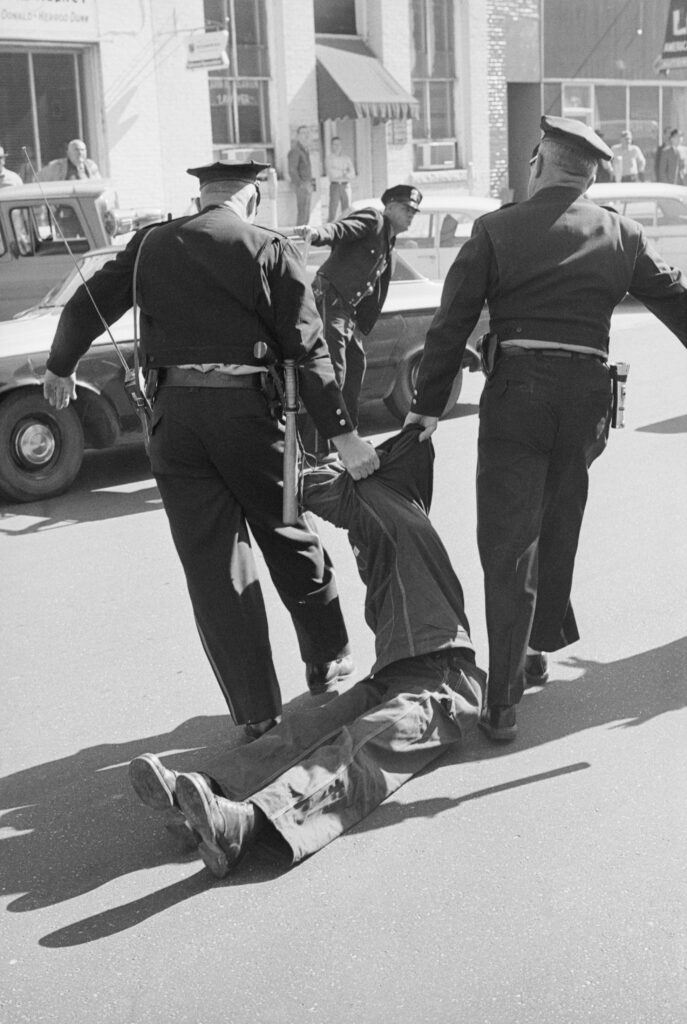

The photo above captures Selma police dragging SNCC Member Willie Lawrence McRae to jail for blocking the sidewalk. Unjust and constant police harassment targeting African Americans was a primary reason why many SNCC members began to turn from nonviolence.

During John Lewis’ term as chairman from 1963 to 1966, the organization favored provocative—yet nonviolent—direct action. When the Supreme Court outlawed segregated interstate busing in December 1960, SNCC joined the Congress of Racial Equality on a series of “Freedom Rides” throughout 1961 to test the decision.

In 1964, SNCC took part in “Freedom Summer,” a multi-organizational effort to expand voting and civil rights in Mississippi. In 1965, Lewis led marchers across the Edmund Pettis Bridge during the famous Selma to Montgomery march to protest the police murder of activist Jimmie Lee Jackson.

White supremacists met these protests with violence. They firebombed a bus carrying Freedom Riders in Anniston, Alabama, murdered Freedom Summer workers, and assaulted marchers—fracturing Lewis’ skull.

It became clear that recalcitrant whites were going to do everything they could to keep Blacks subjugated. This helped radicalize SNCC’s membership and solidified their belief that African Americans needed political power to achieve self-determination.

In 1965, SNCC launched voter registration and political education projects in places like Lowndes County, Alabama. Lowndes was such a notoriously violent place for Blacks that SNCC leaders like Stokely Carmichael believed they would have free reign to experiment with more radical methods.

As in much of the rural South, many Blacks there already carried guns. When SNCC arrived, the county became a test case for the efficacy of armed self-defense. Harassment continued, but SNCC activists working alongside local Black citizens achieved their goals with little physical harm.

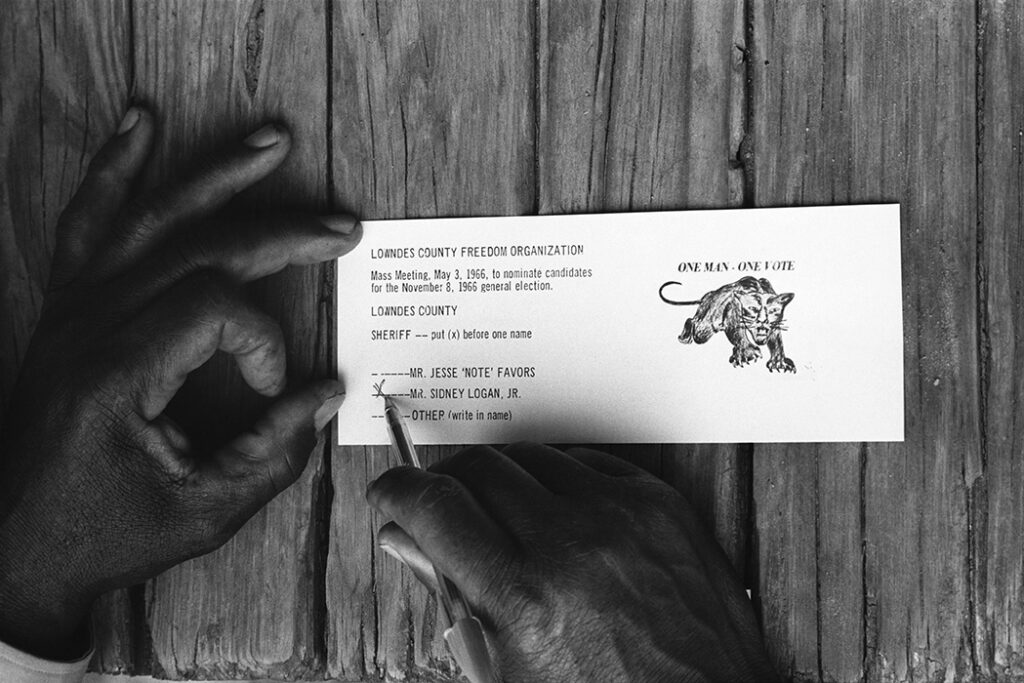

When they finished their work, Lowndes County had a slew of new Black voters, candidates, and an independent political party (the Lowndes County Freedom Party). The picture below shows the fruits of their labor—Black hands casting a vote to place a Black candidate on the ballot. Before SNCC’s involvement, it would have been an audacious and suicidal act in the county known as Bloody Lowndes.

Shortly after the departure from Lowndes County, SNCC fell into a sharp decline. The successes there emboldened members who believed in militant principles tied to the emerging “Black Power” Movement of the late 1960s. In 1966, many of SNCC’s members came to doubt that white liberals could be counted on to fight for Black liberation, and after a close vote, whites were expelled from the organization.

The organization at first had been known for prolonged and honest deliberation, often holding multi-day meetings until they reached consensus on movement strategies. But after Lowndes, majority rule became the norm, and votes often split narrowly, with sometimes a single vote determining major issues.

Divides among SNCC’s leadership reflected those among the rank and file. Exhausted from years of organizing, many members became radical or disenchanted with the organization. By 1973, it was over.

Still, SNCC’s brief time at the forefront of the civil rights movement remains a success. Its founders’ initial goal was to create a body meant to ease student involvement in the broad fight for justice. From lunch counter sit-ins to voter registration, SNCC’s members met those challenges and consistently inspired positive social change.

Learn More:

Charles M. Payne, I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle, With a New Preface, 2nd edition (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2007).

Akinyele Omowale Umoja, We Will Shoot Back: Armed Resistance in the Mississippi Freedom Movement, Reprint edition (New York (N.Y.): NYU Press, 2014).

Freedom Song, directed by Phil Alden Robinson, Featuring Danny Glover, Vondie Curtis-Hall, and Loretta Devine (Warner Brothers, 2007).