Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

During the mid-1960s, staffers and volunteers for the Voter Education Project traveled across the South. In the summer of 1964, Mississippi became the focus of the project. The events of that summer garnered national headlines due to the Project’s employment of Northern white middle-class college students as volunteers, and for the intense violence used by local whites to oppose it.

Known as Freedom Summer, the 1964 program was part of the Council of Federation Organizations (COFO) greater Mississippi Freedom Project to increase Black voter registration. Activists quickly realized that Black Mississippians needed viable community institutions that could be maintained long after out-of-state volunteers left. Children were a prominent, though often overlooked, presence in the community institution-building drive during the Mississippi Freedom Summer.

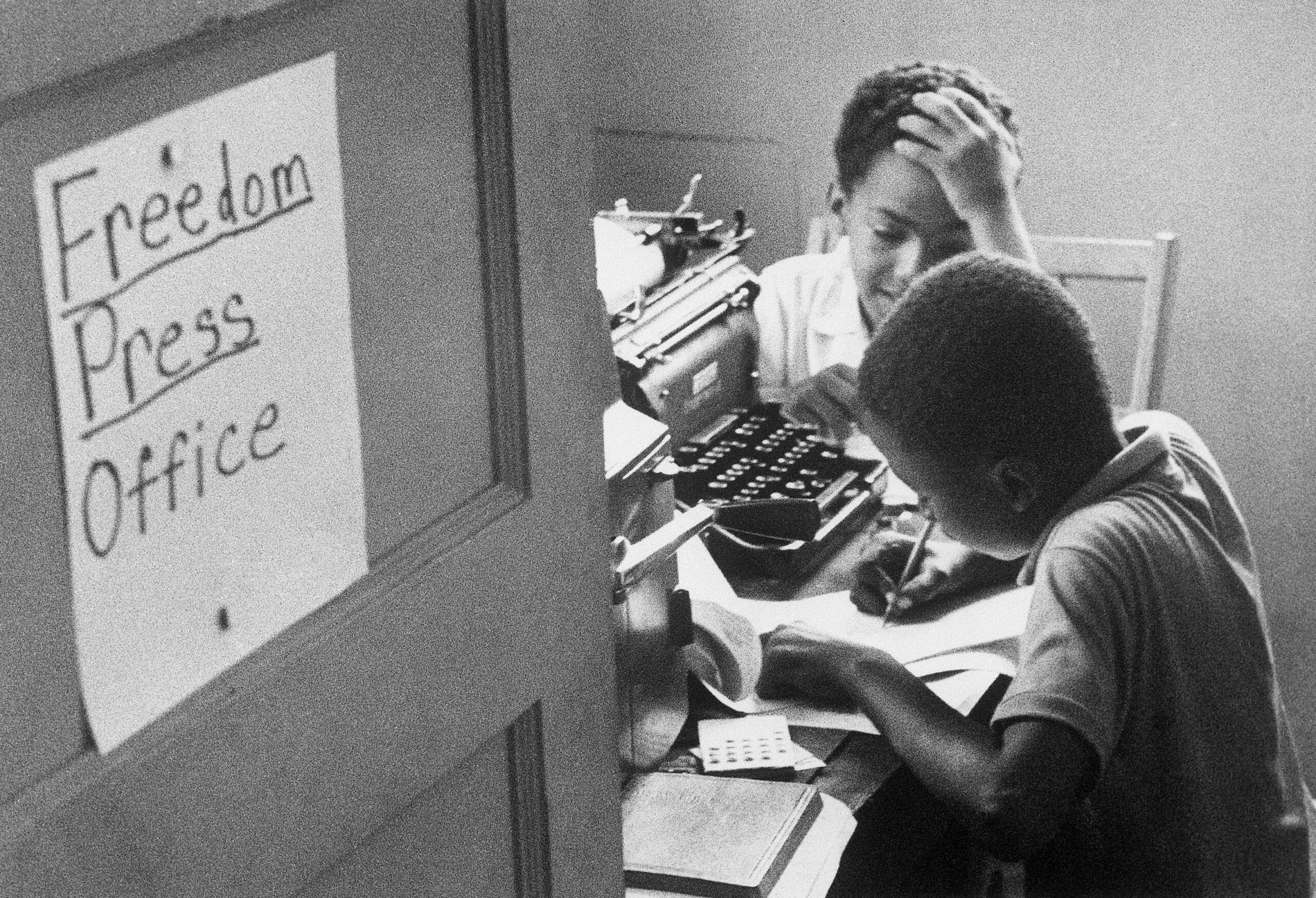

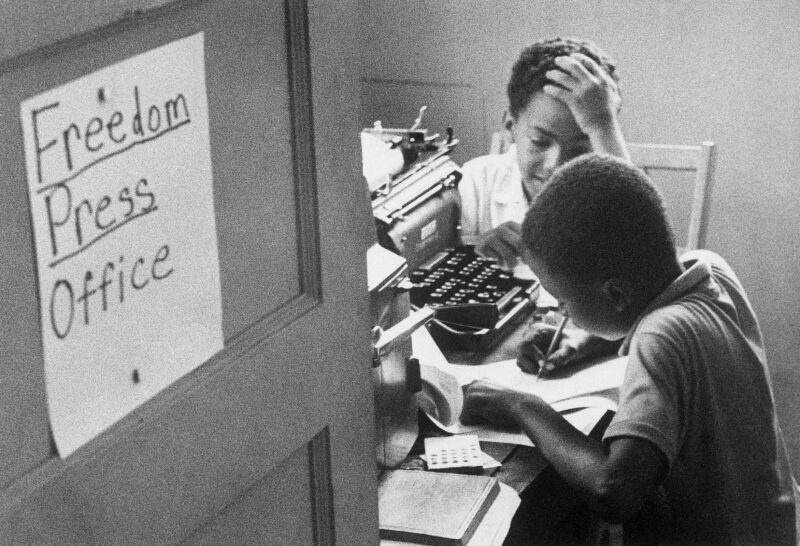

Black children contributed to the Civil Rights Movement through organizing, but their presence also shaped organizing objectives and how activists and volunteers engaged with the Black communities. Black children worked on the Mississippi Freedom Press, attended Mississippi Freedom Schools, and shaped how volunteers maneuvered establishing authentic relationships with local Black communities.

Organizers disseminated information about the state of the local and national movement through the publication of the Mississippi Freedom Press. These movement-oriented newspapers served as crucial sources for those who wanted to be informed and read the news from the perspective of those supporting the Civil Rights Movement.

Pictured above, two boys work in the Freedom Press office in Hattiesburg. Whether working on a task for the publication or simply practicing their writing skills, these boys were learning how important documenting and sharing information was to the movement’s efforts.

Illiteracy was a big concern for activists and community members. Immense disparities between Black and white schools so many years after Brown v Board meant working with children to ensure they could read and write was a critical aspect of the Mississippi Project.

The desire to improve Black children’s education manifested in the formation of Freedom Schools. The COFO’s Mississippi Freedom Schools opened on July 2, 1964, and quickly became an integral part of Freedom Summer. Hattiesburg, where these boys resided, had over 600 Black students enrolled. The boys in the Freedom Press office represent how expansive the Mississippi Freedom Project goals became from the COFO’s initial interest in voter education. Children’s presence and needs led to the creation of Freedom Schools.

The boys working in the office were learning from a curriculum that instilled a sense of pride in them as Black people and encouraged them to become active citizens in the Black freedom struggle, which many children later did. Several students who went to Freedom Schools participated in later protests in Mississippi towns, including Indianola, Cleveland, and Shaw.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

Black children also shaped how volunteers navigated going into Black communities with the hopes of increasing adult participation in Freedom Summer. Volunteers, including white activists, went door-to-door in Black neighborhoods to increase voter participation in their designated areas, explaining the importance of registering to vote.

By allowing white workers in their homes, Black Mississippians knew that they risked reprisal from local whites. Nevertheless, parents and guardians recognized that they needed to expose Black children to a key component of community organizing: trust.

As shown in the picture above, after talking to his parents about voting, a white worker plays with a small Black child. While the worker’s hold is awkward and distanced, it is also firm. This interaction speaks to how many volunteers lacked familiarity with Black communities. However, it is also symbolic of the trust and commitment required to advance voting rights in Mississippi. It is unknown whether the child’s parents decided to register to vote. However, their decision to expose their child to volunteers would not have been made lightly.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

The Mississippi Freedom Press, Freedom Schools, and voter registration drives could not have succeeded without establishing genuine relationships between activists and Black communities. One way organizers created these relationships was through social gatherings.

Pictured above is a moment of laughter and joy. The children in this photo are enjoying the musical styling of a guitarist at one of these gatherings. The use of social gatherings as an organizing tool was not new, but a tactic that can be traced back to union organizing in the 1930s.

Singing freedom songs and other forms of musical expression were important to creating communities. Fellowship between community members and volunteers was a vital component of the project. Parents took their children to Freedom Summer community gatherings. The purpose of these gatherings was to increase local people’s participation, discuss next steps, and socialize with one another. Children’s everyday presence in social life was an expression of organizing.

Time and time again, children became the center of movement work and active participants in shaping their communities; the Mississippi Freedom Summer is only one historical example. The moments captured above highlight elements of movement work that activists did not always document in organizational papers.

Pictured above are children working and learning, but also representing the establishment of trust and genuine relationship building. These elements of community organizing continue to be essential in our contemporary moment.

Learn More:

Payne, Charles M. I’ve Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997.

Carson, Clayborne. In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Franklin, V. P. The Young Crusaders: The Untold Story of the Children and the Teenagers who Galvanized the Civil Rights Movement. Boston: Beacon Press, 2021.

Sturkey, William. “The 1964 Mississippi Freedom Schools.” Mississippi History Now, May 2016. https://mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/issue/The-1964-Mississippi-Freedom-Schools