Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

The Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) evolved out of the pacifist Fellows of Reconciliation and was established as an interracial nonviolent direct-action civil rights organization in 1942. Their early efforts in the 1940s and 1950s included a series of nonviolent boycotts to desegregate lunch counters and schools in Northern and Midwestern cities.

When the Supreme Court ruled, in Morgan v. Virginia (1946), that segregation on interstate buses was unconstitutional, CORE sent an interracial group of men on a two-week Journey of Reconciliation through Virginia, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky to test the compliance of southern states. However, after a series of arrests the group only reached as far south as North Carolina before returning to Washington, D.C.

After barely surviving government attacks on leftist organizations during the Cold War, CORE restructured its local chapters and initiated public desegregation efforts in local communities.

By the time four Black college students sat at a whites-only lunch counter on February 1, 1960 in Greensboro, North Carolina, CORE was positioned to provide immediate support to the student protesters. Following the success of the sit-in movement, CORE implemented its earlier strategy of sending interstate buses of interracial passengers South in the political climate of the 1960s.

When the Supreme Court extended the Morgan case and ruled in Boynton v. Virginia (1960) that racial segregation in interstate travel was illegal on buses, trains, and in transportation terminals, CORE reignited the strategy used during the Journey of Reconciliation and launched the first Freedom Ride on May 4, 1961. The group of men and women intended to ride from Washington D.C. to New Orleans. However, violence in Virginia and the Carolinas resulted in the arrest of over 300 riders and an assault on civil rights leader John Lewis.

Violence in southern states continued when the Rides resumed two weeks later. The above image shows the moments after a white mob set fire to a bus occupied by members of the Freedom Riders in Anniston, Alabama on May 14, 1961. The mob saw the bus at the town terminal, stoned it, and slashed the tires before following the bus from town. Despite their obscured faces, the image captures the riders in distress following their assault.

The firebombing coincided with an assault on Freedom Riders on another bus leaving Atlanta for Birmingham, Alabama. With the help of Birmingham Public Safety Commissioner Bull Conner, a group of Klansmen were waiting for their arrival. Klansmen beat the passengers as they descended from the bus.

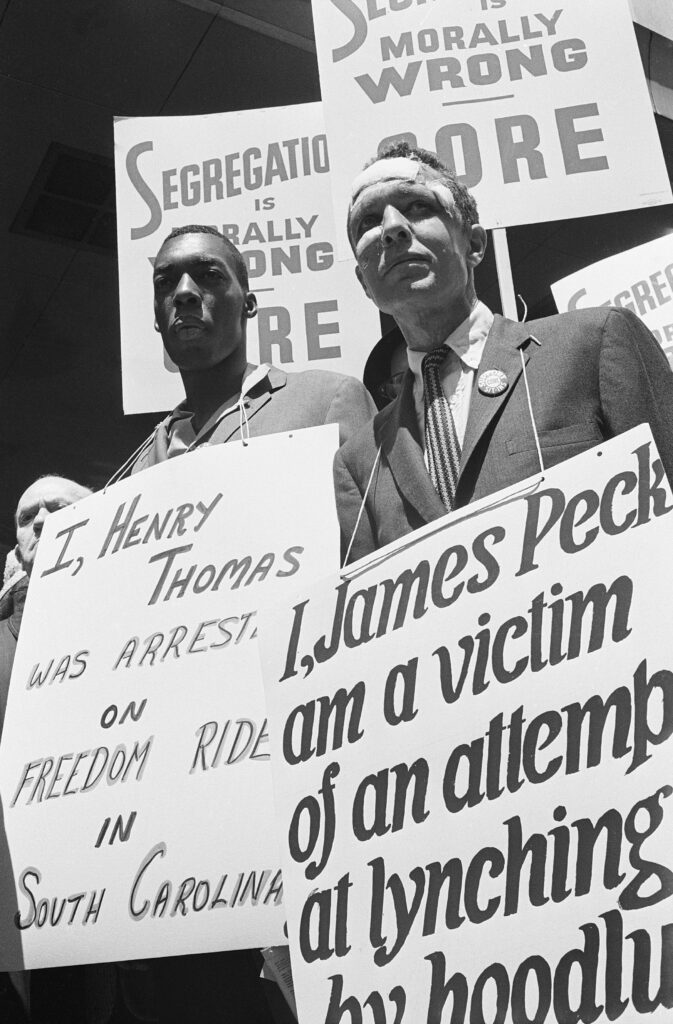

The image below captures two victims of these racist attacks on freedom, Henry “Hank” Thomas and James Peck. Thomas is shown with a placard indicating his arrest in South Carolina during the first Freedom Ride earlier in the month. Peck was severely beaten by Klansmen in Birmingham and required fifty stitches.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

Captured roughly a week after the attack, Peck is shown still healing from his injuries and carrying a placard accusing his assaulters of attempted murder. The image highlights the solidarity of Black and white people engaging in direct nonviolent action together that was central to CORE.

On May 20th, the Freedom Rides resumed and were set to depart Montgomery, Alabama for Jackson, Mississippi. With the help of Highway Patrol and the National Guard, the buses arrived in Jackson without incident, though the riders were arrested when they attempted to use the white-only facilities at the depot and were given 67-day jail sentences.

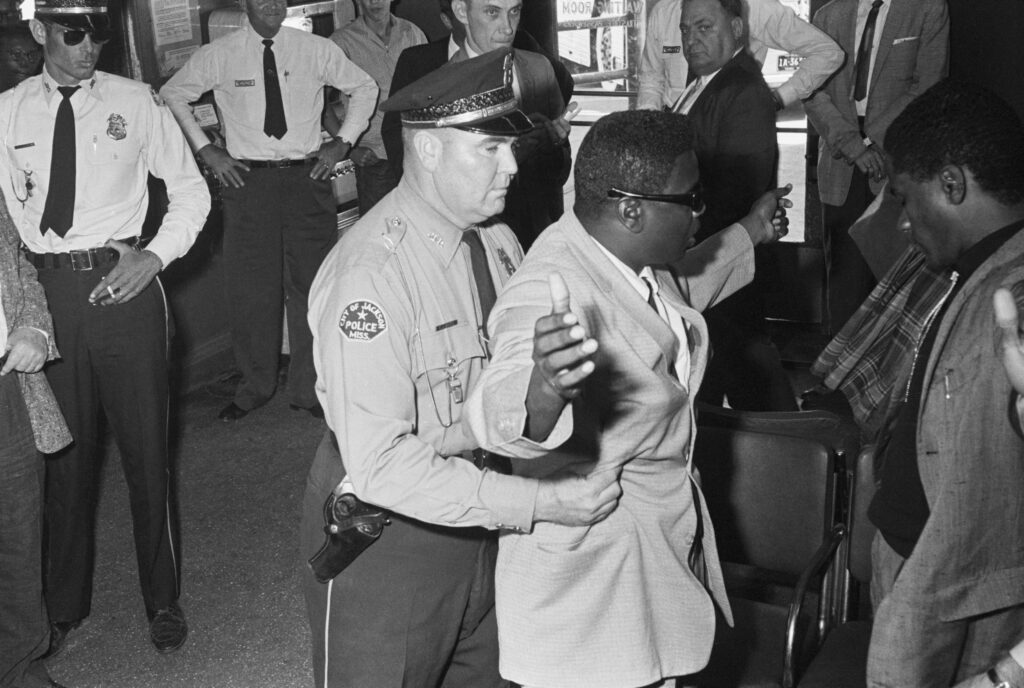

Shown below is a Freedom Rider being searched by a Jackson police officer after being charged with the “breach of peace.” Seventeen others were also jailed on this charge. As displayed in the picture below, police harassment was a tactic used by law enforcement to prevent challenges to the southern status quo.

Photo by Bettmann Collection/Getty Images

The arrests and harsh sentences imposed on the riders mobilized every CORE chapter in the nation, which in turn solidified its centrality to desegregation efforts in the Civil Rights Movement. CORE chapters organized to end Jim Crow segregation, political disenfranchisement, and employment discrimination. In 1963, the organization helped to organize the March on Washington for Freedom and Jobs.

During the following year, CORE, along with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), helped to organize the “Freedom Summer” campaign to end Black political disenfranchisement in the Deep South, particularly in Mississippi.

Under the umbrella coalition of the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO), activists established 30 Freedom Schools throughout Mississippi that taught Black history and the philosophy of the Civil Rights Movement.

Almost immediately the Freedom Summer campaign became the target of white violence. Three CORE field workers, James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, went to investigate the arson fire of a Freedom School near Philadelphia, MS. The three were murdered by Klansmen on June 21, 1964. Their murders brought nationwide attention to the campaign.

The murders radicalized CORE members who began to question the philosophy of nonviolence and white involvement while the organization increasingly leaned towards a Black militant orientation by 1966. Despite the reactionary shift to Black nationalism in later years, CORE-sponsored Freedom Rides cemented the organization’s role in desegregation and helped pave the way for the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Learn More:

Barnes, Catherine A. Journey from Jim Crow: The Desegregation of Southern Transit. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1983.

Marable, Manning. Race, Reform and Rebellion: The Second Reconstruction in Black America, 1945-1982. London: MacMillan Press, 1984.

Farmer, James. Lay Bare the Heart: An Autobiography of the Civil Rights Movement. Fort Worth, TX: Texas Christian University Press, 1985.

Hollars, B.J. The Road South: Personal Stories of the Freedom Riders. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2018.