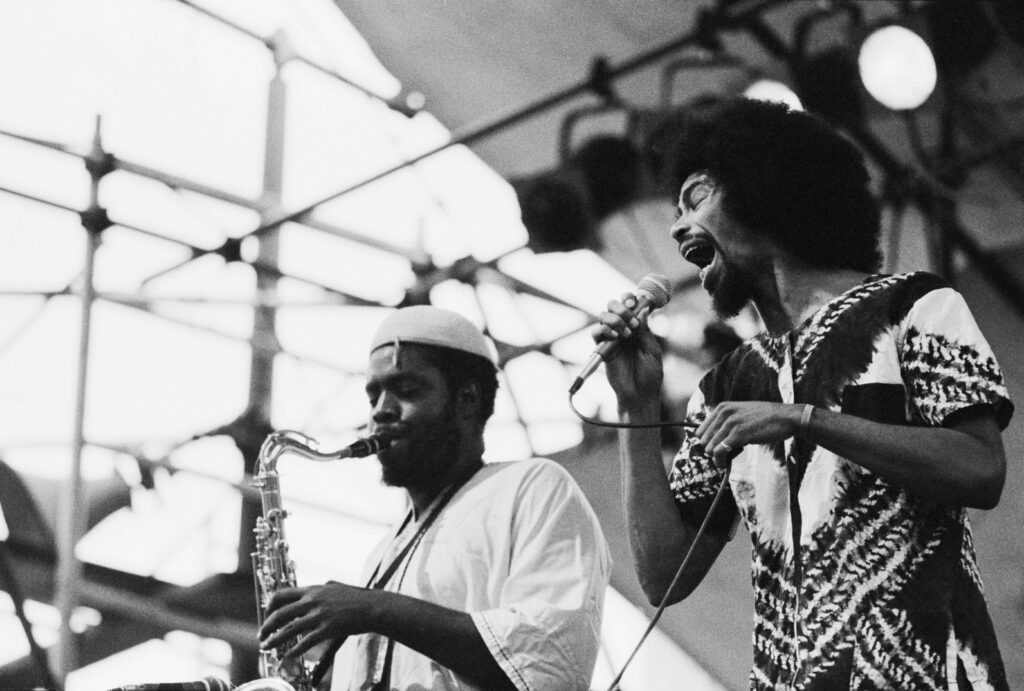

Photo by David Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images

Gil Scott-Heron died too soon. He was just 62 years old when he passed away in 2011. Tragic on its own terms but even more so because he recently returned to public attention.

A year earlier Scott-Heron had released a new album, I’m New Here, his first in 16 years, and started performing live again. He had always been skinny, almost scrawny, but performing here at the Coachella Festival in 2010 he was grey and gaunt.

Photo by Anna Webber/Getty Images

By that time, Scott-Heron had been labelled: the godfather of rap, the progenitor of hip-hop. Scott-Heron didn’t much like that moniker. “I don’t know if I can take the blame for it,” he told an interviewer in 2010. Hip-hop is “something that’s aimed at the kids,” he told another. “I have kids, so I listen to it. But I would not say it’s aimed at me. I listen to the jazz station.”

He preferred the term “bluesologist” to describe himself.

Maybe these were the complaints of a grumpy older man who just didn’t appreciate what the kids these days were up to. But perhaps Scott-Heron’s spiky relationship with hip-hop, and by extension the way it seemed to define his legacy, reflected a larger difficulty figuring out just what kind of artist Gil Scott-Heron was.

A poet, yes, and a writer more broadly. He had published a book of poetry and two novels by the time he was 23. He picked up an MFA in Creative Writing from Johns Hopkins.

“Where I’m coming from is closer to Langston Hughes than Huey Newton,” he said in one interview. But in 1969 while a college student at Lincoln University, an HBCU outside of Philadelphia, Scott-Heron saw a performance of the Last Poets, and the experience pointed him in the direction he wanted to go.

The Last Poets, one of the most significant products of the Black Arts Movement, recited their poetry often accompanied by Conga drums. Poetry as performance, and after the show Scott-Heron reportedly approached the group and asked: “Can I start a group like you guys?”

He had first written “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” the piece that would put him on the cultural radar, in 1968, but in subsequent iterations and releases the spoken-word lyrics are supplemented by more instrumentation.

By the early 1970s, Scott-Heron had found his form: poetry sung to a melody; songs with cultural commentary more than ordinary lyrics. Inventive, genre-busting, intensely personal and political at the same time.

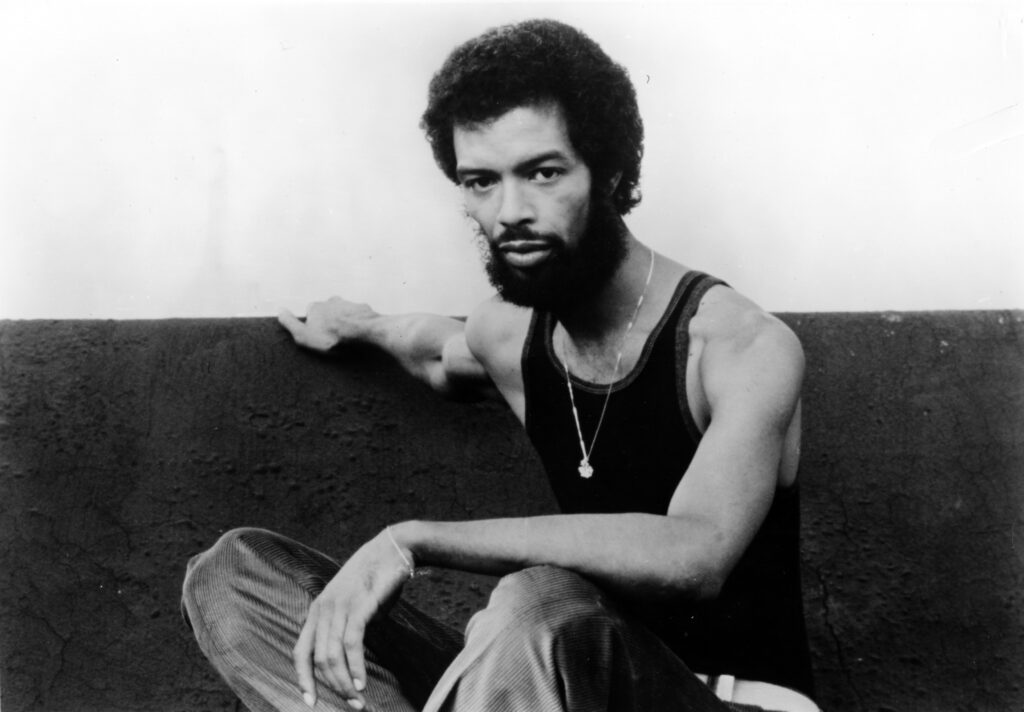

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Those early years were astonishingly productive for Scott-Heron, and in this photograph at the start of this period he stares at us confident and cool. One of the first artists signed to the new Arista Records in 1975, he made nine albums with flutist Brian Jackson in the space of ten years. Unfortunately, those albums never quite achieved the commercial success that the company had hoped for, and Arista dropped Scott-Heron in 1985.

Songs like “Revolution” and “Whitey on the Moon” (1970) commented on Black political issues and struggles in the United States. But Scott-Heron’s concerns were broader.

He wrote two songs, for example, demanding we take the dangers of nuclear power seriously.

“We Almost Lost Detroit” (1977) is a quiet, plaintive piece about the partial meltdown of Fermi 1, a nuclear reactor just south of the city. He performed that song at the 1979 “No Nukes” concert in New York.

“Shut ‘Em Down” (1980), the first track on the album 1980, is a raucous piece that begins with ominous rumblings at the low end of a piano before bursting into a danceable tune with horns and back-up singers.

He released the song “Johannesburg” in 1975, and that tune helped catalyze the anti-apartheid movement around the world. As people began to gather at any number of anti-apartheid marches, pickets, and demonstrations, someone would yell “What’s the word?” into a megaphone and the crowd would yell back “Johannesburg!” and we were off.

He played at many anti-apartheid concerts including at Clapham Common, London in 1986, performing to a crowd estimated at 250,000 strong.

Then there were songs about people’s personal demons. “Bottle” (1974) and “Angel Dust” (1978) both stare the problems of addiction squarely in the face.

“Angel Dust” was Scott-Heron’s most commercially successful single. Prescient too as it would turn out. “Down some dead-end streets there ain’t no turnin’ back,” he sang, but that’s ultimately where he went. He wrestled with addiction, particularly to crack cocaine, and did two stints in prison for drugs. He was still using heavily when I’m New Here came out.

He remained fierce to the end but addiction left him diminished, a long way from the charismatic performer he was at this 1973 show.

Whether he liked it or not, Scott-Heron has been hugely influential on rap and hip-hop and on other music besides. You can hear samples of him all over the place. But he never enjoyed much mainstream success. He remains a musician other musicians revere even if listeners don’t quite know where the samples come from.

The lyrics themselves, many of them, are so rooted in their particular moment that they simply fly over the heads of many under a certain age. An online version of “Revolution” comes with annotations explaining what the “tiger in your tank” and the “giant in your toilet bowl” refer to. Political and cultural references that were biting when a song came out have grown dated in another generation.

Many of his songs, but not all of them. “Winter in America” (1974) has been in my head a lot as I write this early in 2025. “Democracy is ragtime on the corner,” he sings, and that doesn’t feel dated at all.

Learn More:

“The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” (1968)

“Whitey on the Moon” (1970)

“Bottle” (1974)

“Winter in America” (1974)

“Johannesburg” (1975)

“We Almost Lost Detroit” (1977)

“Angel Dust” (1978)

“Shut ‘Em Down” (1980)