Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

In the 1970s, Atlanta had strategically created an image of itself as “the city too busy to hate.” It was viewed as a hub for a thriving Black middle class that had elected its first Black mayor, Maynard Jackson, in 1973.

However, the above image of the two sisters, 10-year-old Jaelinee (right) and 9-year-old Jotonya Mason (left), sitting with jackets that say “Let The Children Live” tells a different story, one about the limits of “black faces in high places” as an indicator of Black racial progress and a shield from antiblack violence.

Instead of playing in the park or otherwise enjoying the protected pleasures of childhood, these two young girls have become evidence-seekers of their disappeared and murdered peers in what we now call the Atlanta Child Murders. These were a series of disappearances and murders of at least 28 poor Black children in Atlanta between 1979 and 1981.

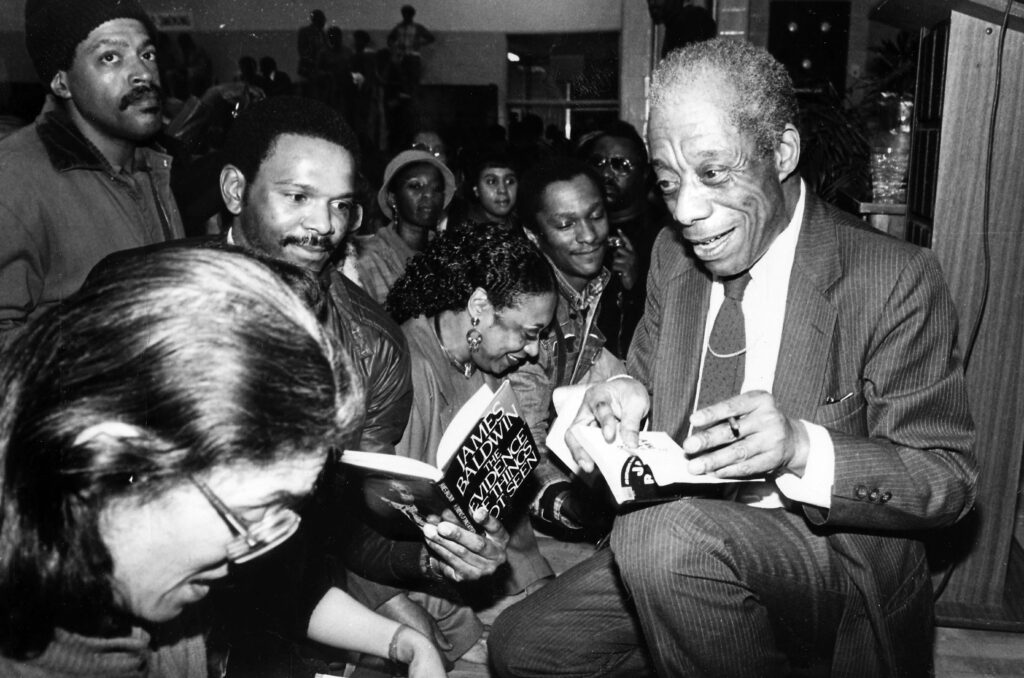

Amidst media sensationalism, the moment called for ethical witnesses, and James Baldwin responded by writing the book, The Evidence of Things not Seen (1985). In this photograph, we can see Baldwin promoting the book which was originally published in 1981 as an essay in Playboy commissioned by Walter Lowe. Jr.

Photo by Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

In his last yet least known book, Baldwin argues that the racialized violence that was happening in Atlanta was reflective of “the ancestral, daily, historical truth of Black life.” For Baldwin the Atlanta Child Murders were not an aberration but rather a prime example of the failures of integration.

In Evidence, Baldwin demonstrated that the nation’s apathy towards Black children had a precedent. It existed during slavery in the ways Black children were ripped from their mothers, through the brutal murder of Emmett Till, and in the 16th Street bombing, when planted explosives killed four little girls—Addie Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley—in the basement of a Birmingham church in 1963.

In the photograph below, we see Baldwin protesting the Birmingham Church Bombing, and the subsequent murders of two teens—Johnny Robinson and Virgil Ware—who were shot by police in the aftermath of the bombings.

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

The sociohistorical context Baldwin offered in Evidence was significant because it allowed him to write against the publicized spectacle of the murders, a spectacle that led Baldwin to call Atlanta a “grotesque Disneyland.”

While white America had historically treated Black children as disposable, what haunted Baldwin was the issue of Black complicity in this terror. He observed that Atlanta’s majority Black administration had shown negligence in investigating the case. For Baldwin, this revealed how the economic opportunities presented by integration had politically pacified the city’s Black middle class.

Baldwin argued that the Black administration in Atlanta—mediated by the concerns of white elites—cared about the murders not as a concern for the lives of the Black children, but rather as a way of managing the image of the city. Leaders undermined the seriousness of the case by framing the missing and murdered as “delinquents” and “runaways.”

The parents of the missing and murdered were also accused of being complicit in the deaths of their own children. Camille Bell, the mother of Yusef Bell, one of the murdered, along with the Committee to Stop Children’s Murders (STOP), was at the forefront of urging the administration in Atlanta to take the cases seriously. However, Camille and STOP were constantly discredited and vilified by the city.

This divide between the concerns of poor Black Atlantans and those of the middle class, according to Baldwin, demonstrated the ways blackness itself was not a unifying category that could be used to organize against anti-black violence as had been imagined in the 1960s.

This question of Black folks’ responsibility to one another (or lack thereof) was further brought to fore when a 23-year-old Black man named Wayne Williams was convicted of the murders of two men, and then subsequently linked to the Atlanta Child Murders—though he was never tried for them.

Baldwin contended that Williams could not have committed those murders, a prevailing sentiment of many community members. In the city’s failure to conduct an adequate investigation, Baldwin argued that Williams became one of the slain children.

Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

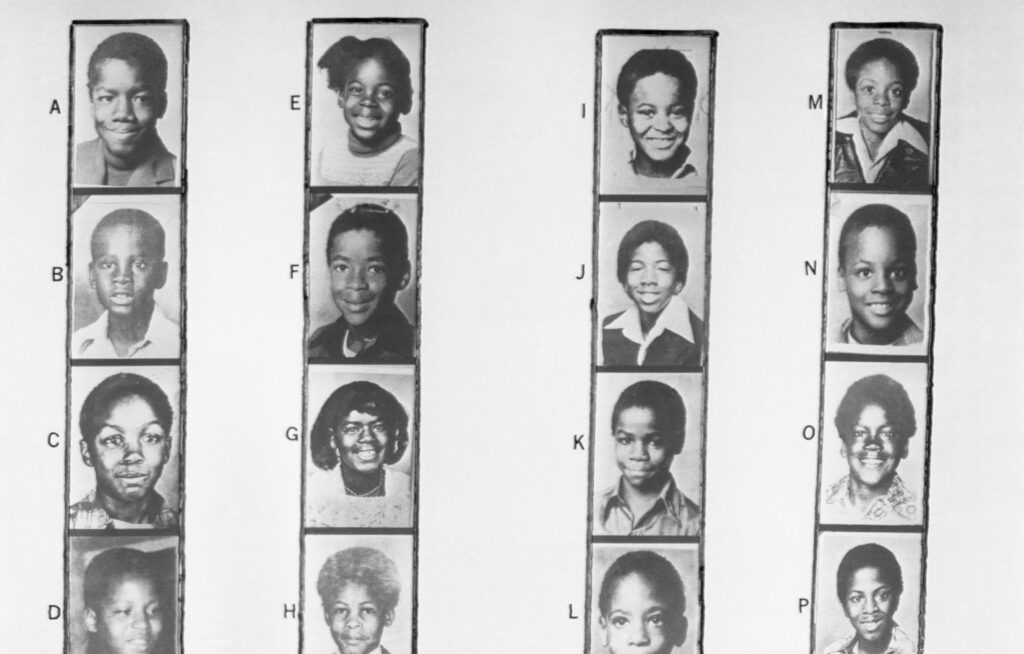

What then is owed to the missing and murdered?

In this photo sheet we can see the faces of some of the murdered children. Those faces compel us to follow Baldwin’s call to “bring out our dead.” Baldwin’s call is not simply to remember the dead but to claim the deaths as our own.

Though Evidence did not receive critical praise, Baldwin’s book was not alone among works that function as keepers of memory, works that tend to the dead through claiming.

This act of claiming these deaths became the political imperative of other cultural workers in the 1980s, like Toni Cade Bambara, June Jordan, and Faith Ringgold, who took up the Atlanta Child Murders within their works. They all countered the narrative of the government and media’s official account of the terror as spectacle. Their works release us from being beholden to these “official accounts,” which cannot make articulable the terror of anti-blackness and the care practices that make it survivable.

The case of the missing and murdered children was reopened in 2019 by Atlanta’s former Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms because it was suspected that the Ku Klux Klan may have been involved.

As we move towards this reckoning, we must consider what conditions must exist to adhere to the mandate covered by Jailene and Jotonya of “Let the Children Live?”

For Baldwin, this kind of world would necessitate that we lean into community which, in turn, would require “an endless connection with, and responsibility for each other.” No longer is this responsibility tied to imagined identitarian categories of allegiance but a willingness to claim one another.

Learn More

Baldwin, James. The Evidence of Things Not Seen Book. Henry Holt and Company, 1985.

“James Baldwin Discusses His Book ‘The Evidence of Things Not Seen.’” The WFMT Studs Terkel Radio Archive, 22 Nov. 1985.

“Atlanta’s Missing and Murdered: The Lost Children: Official Website for the HBO Series.” HBO, 2020.

Casey Cep, “When James Baldwin Wrote About the Atlanta Child Murders”.

Kruse, Kevin M. White Flight: Atlanta and the Making of Modern Conservatism. Princeton University Press, 2005.

Hobson, Maurice J. The Legend of the Black Mecca: Politics and Class in the Making of Modern Atlanta. University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

Wood, Augustus. Class Warfare in Black Atlanta: Grassroots Struggles, Power, and Repression under Gentrification. University of North Carolina Press, 2025.

Bambara, Toni Cade. Those Bones are Not My Child. Pantheon, 1999.