Photo by Charles Peterson/Archive Photos/Getty Images

The familiar, yet superficial history of rock and roll begins in the early 1950s with Cleveland disc jockey Alan Freed crowing “That’s Bill Haley and the Comets rockin’ and rollin’ you with ‘Shake, Rattle and Roll.’” Yet a much deeper history exists and a more complex set of origins.

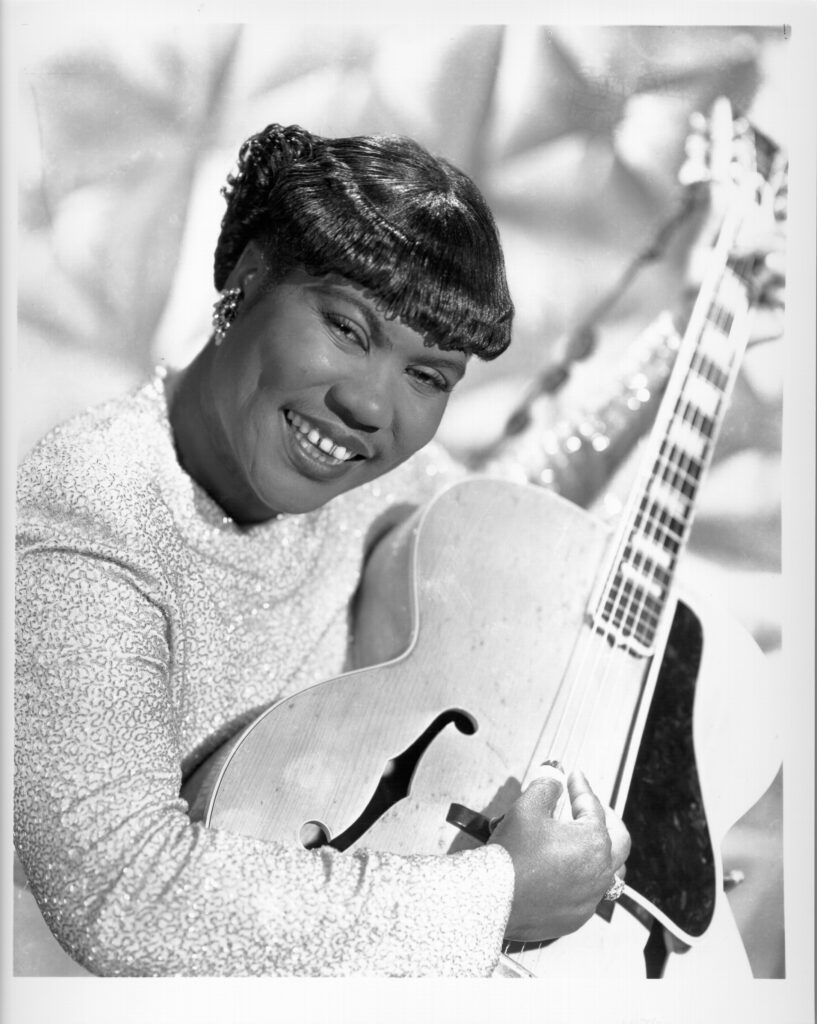

On March 20, 1915, one of the most influential, if largely forgotten, creators of rock and roll was born – Sister Rosetta Tharpe (pictured below in 1950).

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Tharpe was born Rosetta Nubin (Tharpe being her first husband’s name) in Cotton Plant, Arkansas. A musical prodigy, by the age of six she was touring with her mother throughout the South, singing and playing guitar, not just as an entertainer but as an evangelist.

She was raised in the Church of God In Christ, an African-American Pentecostal denomination that saw gospel music as not merely accompaniment for services but as a way to win souls for the Lord. In the photo below, Sister Rosetta Tharpe (center) poses for a portrait with her backup singers, The Rosettes, circa 1950.

Photo by Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Her later career would span many musical genres: Tharpe was inducted into the Blues Hall of Fame and was called both the “Queen of Hot Gospel” and the “Godmother of Rock and Roll.” But, as the appellation “Sister” affirms, she never left gospel music, though her secular music would alienate some of her fans who saw blues and jazz as “the devil’s music.”

By her early twenties, Tharpe had moved to New York City and was playing the Cotton Club alongside Cab Calloway. She was one of the stars of a 1938 Carnegie Hall concert of black music, “From Spirituals to Swing.” In the 1940s, she had success with recordings on both the gospel and popular Harlem Hit Parade Billboard charts—notably 1944’s “Strange Things Happen Every Day.”

In August 1939, photographer Charles Peterson captured Tharpe in this musical moment: with Duke Ellington playing guitar and Cab Calloway playing piano during a jam session at a private party hosted by Hearst political cartoonist Burris Jenkins, in his New York City studio. The guests included, from left to right, Rosetta Tharpe, Duke Ellington, trumpeter Rex Stewart, Cab Calloway, an unknown guest, and Duke’s big band vocalist, Ivie Anderson.

Photo by Charles Peterson/Archive Photos/Getty Images

Tharpe was ahead of her time in other ways as well. In 1951—a year prior to Alan Freed’s “Moondog Coronation Ball,” which has often been considered the first rock and roll concert—Tharpe played amplified electric guitar in the Washington Nationals’ stadium to a crowd of 20,000, complete with fireworks.

And, presaging celebrities’ self-promotion from Tiny Tim to the Kardashians, the sold-out performance was her own (third) wedding. She was also a talented electric guitarist, who combined blues, jazz, and boogie-woogie into a loud, flamboyant, virtuoso style that only later would be called “rock and roll.” Her electric guitar riffs recorded in the 1940s sound like those Chuck Berry would record a decade after.

In the photograph below, Tharpe played electric guitar at Wilbraham Road Station in Manchester, England, while filming the Granada Television special Blues and Gospel Train, on May 7, 1964.

Photo by TV Times/Getty Images

Rumors of Tharpe taking female lovers—both confirmed and disputed by her close associates—followed her during her career, which may have also contributed to some in the gospel community turning their backs on her. In her life Tharpe crossed many boundaries: of genre (playing both gospel and secular music), of gender (playing in a “male” style on a “male” instrument), and even of sexuality.

Tharpe’s career was cut short when she died of complications from diabetes in 1973, at the age of 58.

Tharpe has not been given her historical due for several reasons. First, many of the seminal moments in rock and roll—Elvis Presley on Ed Sullivan, Jerry Lee Lewis on Steve Allen—occurred on the segregated media of radio and television. Second, she suffered from the sexist assumption that the rock guitar is a “male” instrument.

Finally, she may have experienced a kind of “ageism,” the myopic view of postwar popular culture as exclusively a youth culture. Her 20,000 fans who had packed Griffith Stadium were mostly middle-aged church ladies, not the screaming teeny-boppers who would fill Shea Stadium for the Beatles.

Photo by David Redfern/Redferns/Getty Images

Tharpe was never forgotten by her musical peers and successors, however. The list of performers who cite her as an influence includes Elvis, Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Johnny Cash, Aretha Franklin, and Isaac Hayes, to name just a few. In the photo above, she is performing onstage at Hammersmith Odeon, London in 1967, playing a Gibson Barney Kessel guitar.

With the centenary of her birth in 2015, there was a resurgence of interest in Sister Rosetta Tharpe, in no small part due to the efforts of her biographer, Prof. Gayle Wald, who wrote several articles and a book about her.

A tribute album of covers of her songs was released in 2003, including artists such as Michelle Shocked, Bonnie Raitt and Sweet Honey in the Rock. Over 100 years after her birth, Sister Rosetta Tharpe is enjoying a richly deserved comeback.

Learn More:

Gayle Wald, Shout, Sister, Shout! The Untold Story of Rock-and-Roll Trailblazer Sister Rosetta Tharpe (Boston: Beacon Press, 2007)

Shout, Sister, Shout: A Tribute to Sister Rosetta Tharpe. (M.C. Records. August 13, 2003)