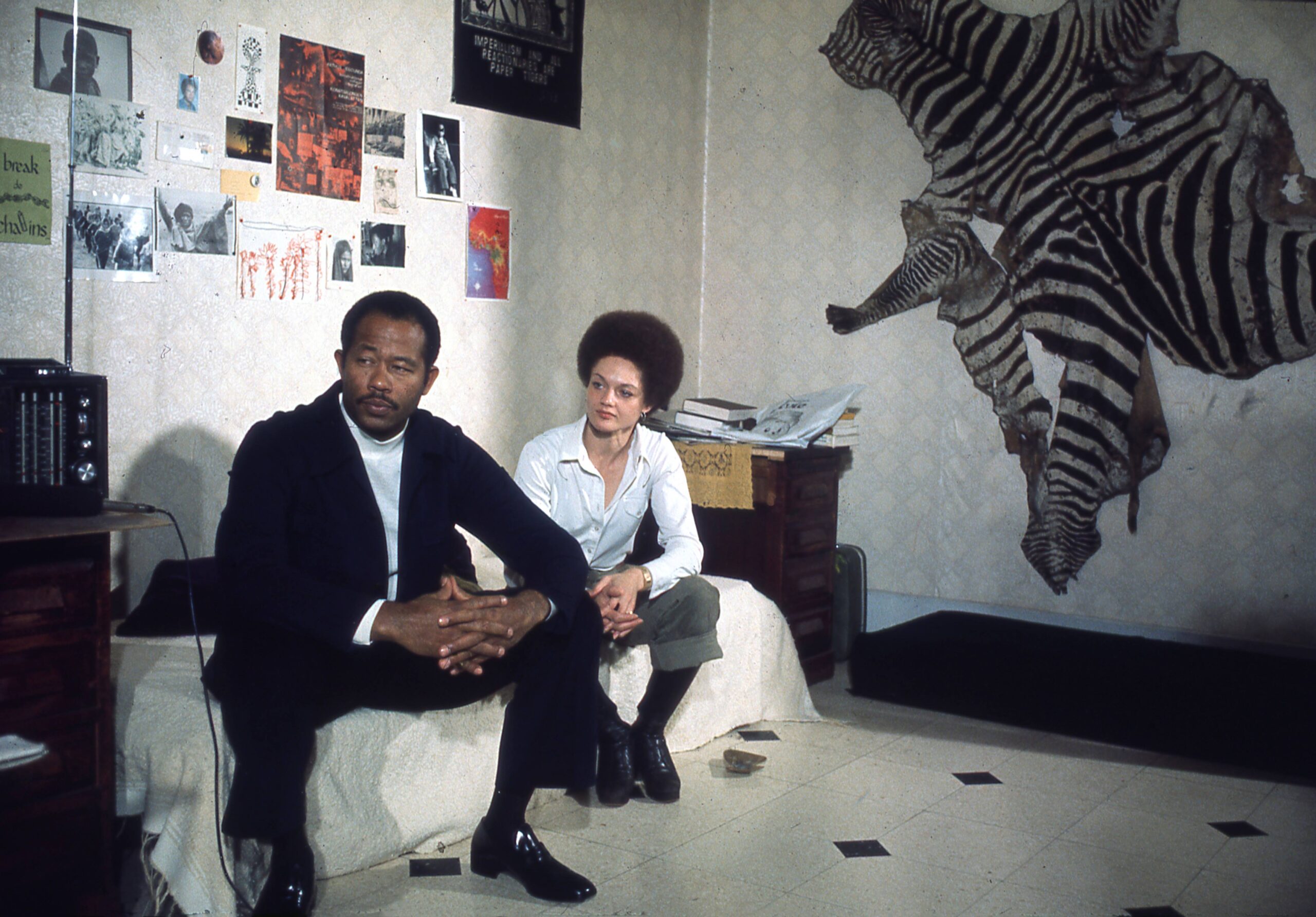

Photo by Nik Wheeler/Corbis via Getty Images

Eldridge Leroy Cleaver gave his final interview in 1997, one year before his death. The former revolutionary declared he “saw the writing on the wall” and lamented that “there is no place for an Afro-American liberation movement.” Eldridge’s ex-wife, Kathleen, recalled seeing him for the last time, looking “far older” than his 61 years, in a “poorly fitting suit…salvaged from Goodwill.”

Why did Cleaver – who commanded the attention of international media in the late 1960s – die in obscurity three decades later?

Cleaver’s journey from illustriousness to insignificance was a winding one. Like many 1960s Black activists, Cleaver was born in the South – Arkansas – and was part of the exodus of African Americans to the West Coast after 1940.

In his youth, he was thrust into a rapidly evolving urban scene in California. Forays into petty crime landed him in juvenile detention centers and a stint in Soledad Prison at the age of 18. In 1958, Cleaver was convicted of assault and rape – actions he theorized at the time as “insurrectionary” because they defied “the white man’s law” – and spent nearly a decade in California’s prison system.

Photo by Smithsonian/Archive Photos/Getty Images

In prison, Cleaver penned his seminal work Soul on Ice, first published piecemeal in Ramparts magazine. He admitted he had “gone astray” and that his “whole fragile moral structure” had collapsed. Rejecting rape as a political weapon, Cleaver flirted with Marxism and Islam, and his ruminations in Ramparts catapulted him into national fame. Released from prison in December 1966, Cleaver joined the fledging Black Panther Party in Oakland.

This fateful decision propelled him from national renown to international stardom. Cleaver became the Minister of Information for the Party, ran for president in 1968, and, alongside his wife Kathleen, became a leading figure in the daily operations of the Party.

After the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in April 1968, Cleaver decided it was time to up the ante as rebellions spread throughout major U.S. cities. Armed with M16s and shotguns, Cleaver led a botched ambush on police, resulting in the murder of 17-year-old Bobby Hutton.

Facing federal charges, Cleaver fled to Cuba in late 1968. Havana had become a haven for political refugees fleeing the United States, starting with Robert F. Williams in early 1961. Cleaver inherited Williams’ mantle as the most famous Black militant-in-exile, and in Cuba he developed plans for a North American Liberation Front.

His hopes of training Black revolutionaries on the Caribbean island to invade the United States in a “reverse-Bay-of-Pigs” was quickly quashed by the Cuban government. They unceremoniously shipped Cleaver to Algeria, where he surfaced to attend the 1969 Pan-African Cultural Festival.

Disillusioned with the Cubans (and Soviets), Cleaver rapidly used connections in Algeria to seek out allies across the globe. Setting up the Afro-American Center in Algiers, he saw connections between the Palestinian struggle and Black American liberation. The Algerians granted Cleaver’s “International Section” of the Panthers an embassy formerly used by the North Vietnamese.

Cleaver toured North Vietnam and the People’s Republic of China as part of his U.S. People’s Anti-Imperialist Delegation, but his closest contacts came with Pyongyang. He made two visits to North Korea – Kathleen gave birth to the couple’s daughter there – identifying it as a model for Black Americans waging their own liberation struggle.

During these tumultuous years, Cleaver sparred with the great activists of his era – often former allies – from Stokely Carmichael to Panther leader Huey Newton.

As Newton retreated from armed struggle and internationalism in late 1970, Cleaver and Newton entered a bloody physical and ideological war over the future of the Party, one undoubtedly amplified by the FBI’s COINTELPRO. Stateside and with a stronger grasp on the Party, Newton eventually won control. Cleaver tried, but failed, to continue operating the International Section in an increasingly hostile geopolitical climate.

Isolated by 1973, Cleaver fell into despair: “Face it,” he told a journalist, “people…use Internationalism in a very cynical way to further their own nationalist aspirations.”

Dejected, he left Algiers for Paris where he and Kathleen moved into an apartment decorated with zebra hide (captured in the 1974 photo above). He returned to the United States in 1975. Upon his return, he eschewed his former comrades and channeled the spirit of Booker T. Washington.

He proclaimed to Black Americans, “Cast down your bucket where you are,” and argued, “America really needs to take control of the world.” Cleaver abandoned the Palestinian cause and embraced Zionism, even hanging an Israeli flag outside his Berkeley home.

For the next two decades, the militant-turned-maverick flailed around with various endeavors: he dabbled in evangelicalism and Mormonism, synthesized Islam and Christianity into a bad portmanteau called “Christlam,” led a failed clothing startup featuring codpiece pants, toyed with stonemasonry (Cleaver is pictured here in 1982 with one of his works), and ran a recycling business.

Photo by Roger Ressmeyer/CORBIS/VCG via Getty Images

Nothing stuck.

Like his former ally and nemesis, Huey Newton, Cleaver struggled with substance abuse in his last decade. He died, ironically, on May Day 1998, leaving behind a convoluted legacy.

For a time, he was the most recognized U.S. militant-in-exile, armed with a plan of action – a grand strategy for revolution – stretching from East Asia to the East Coast. Cleaver’s life is a window into Black internationalism during the Cold War, from its zenith to its nadir.

Learn More:

Eldridge Cleaver, Target Zero: A Life in Writing (Sr. Martin’s Griffin, 2007).

Sean Malloy, Out of Oakland: Black Panther Party Internationalism during the Cold War (Cornell University Press, 2017).

Alex Lubin, Geographies of Liberation: The Making of an Afro-Arab Political Imaginary (University of North Carolina Press, 2014).

Judy Wu, Radicals on the Road: Internationalism, Orientalism, and Feminism during the Vietnam Era (Cornell University Press, 2013).

Eldridge Cleaver interviewed by Henry Louis Gates Jr., “Eldridge Cleaver on Ice,” Transition, 1997, No. 75/76.