Photo by Bettmann Archive/Getty Images

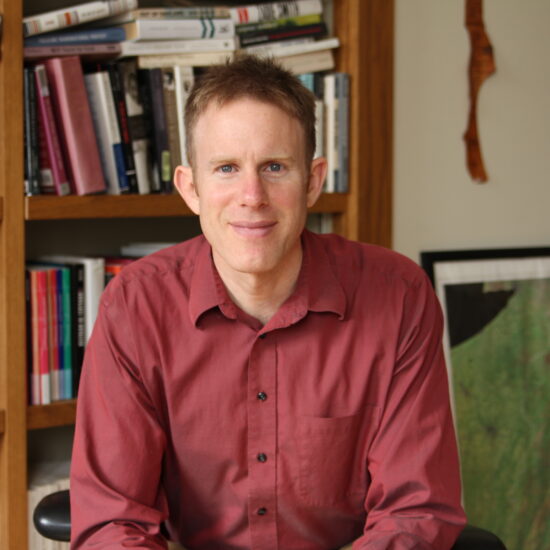

Her eyes are nearly closed. Her face shines with light. The hat that hugs her well-coiffed hair looks like a bouquet of roses. At the heart of the image, her open mouth promises a voice we cannot hear, the voice that captivated some 70,000 people as the photo was taken, the voice that sustained one of the greatest social movements in the history of the world.

It was June 21, 1964, and Mahalia Jackson was on stage at the Illinois Rally for Civil Rights, the second largest gathering in the history of the civil rights movement to that point. The largest gathering, the March on Washington, had also featured Jackson, who had long been a dedicated supporter of the movement. Nearly a decade earlier, she had visited the capital of Alabama to lend support to the Montgomery Bus Boycott and had befriended Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

At the Illinois Rally for Civil Rights, held at Chicago’s Soldier Field, she would yet again share the stage with Dr. King, and would yet again use her voice to support the struggle for freedom. Examining this one image of Jackson offers a window on the social conscience of a great singer, as well as the role of music within the civil rights movement.

The photo’s caption tells us that Jackson is speaking, but she was there to sing. We know that it was her singing voice that attracted many of the people who came to the rally despite the morning rain and blistering afternoon heat. The rally began with two hours of gospel and jazz music. Jackson headed a 5000-voice choir. She sang classic hymns such as “Just a closer walk with Thee” and “I am a poor pilgrim of sorrow”:

I am a poor pilgrim of sorrow,

Cast out in this wide world to roam;

Uncertain of life for tomorrow,

I want to make heaven my home.

Such hymns created a powerful link between the civil rights movement and the African American Christian tradition. The music served as a bridge to the long history of Black struggle, while also bringing together all those listening and singing along.

The rally was itself a form of connection, establishing solidarity between the massive crowd in Chicago and the ongoing struggle in the South and creating connections that could advance the struggle against racial inequities in both localities.

Jackson herself was a child of the Great Migration that brought so many African American families to the large cities of the North and West. Born in New Orleans in 1911, Jackson moved to Chicago as a teenager. While her commitment to civil rights often took her to the South, she was equally committed to supporting Black struggles within Chicago.

Jackson also embodied the vital role women played in the civil rights struggle. Like Nina Simone or Lena Horne, Jackson was one of the most prominent female performers to use their talent to support the struggle. At the rally in Chicago, the two main speakers were both men: Dr. King and Reverend Theodore M. Hesburgh, president of the University of Notre Dame.

It matters that women were routinely denied prominent speaking roles, but it also matters that music allowed some to claim the spotlight.

Women also provided much of the grassroots leadership of the movement, and it was at the grassroots, in people’s homes and small churches, that most of the singing of the movement happened. While groups like SNCC’s freedom singers or famous performers like Jackson raised funds and publicity for the cause, music also permeated every level of the movement, providing solace and inspiration for a struggle whose end remained unclear.

As Jackson sang at the Illinois rally, the 1964 Civil Rights Bill was moving steadily toward becoming law. “We have come a long, long way in the civil rights struggle,” Dr. King told the crowd, “but let me remind you that we have a long, long way to go.”

He added, “Passage of the civil rights bill does not mean that we have reached the promised land in civil rights.” Here again, the power of music provided a chance for all those present to reflect on the struggles of the past and to find renewed strength for the challenges to come.

Learn More:

Jules Schwerin, Got to Tell It: Mahalia Jackson, Queen of Gospel (Oxford University Press)

Ruth Feldstein, How It Feels to Be Free: Black Women Entertainers and the Civil Rights Movement (Oxford University Press)

Guy and Candie Carawan, editors, Sing for Freedom: The Story of the Civil Rights Movement Through Its Songs (NewSouth Books)